Based on media reports, you might think that all public school teachers receive gold-plated health care benefits. While there are some outliers, on average teachers receive benefits that are slgihtly beyond average but not extravagant. Here are three key facts* that shape public perception around teacher health care benefits:

Fact #1: Teachers are much more likely to receive health care benefits than employees in other fields. This is a big discrepancy. Two-thirds of all employees in the private sector have access to medical care benefits through their employer, whereas 99 percent of public school teachers do. Teachers are also far more likely to receive retiree health benefits than their peers in the private sector.

Teachers are also more likely to have access to other health care benefits. Compared to their private-sector peers, teachers are more likely to have access to dental care (58 versus 42 percent), vision care (36 versus 23 percent), and prescription drug coverage (97 versus 66 percent).

Fact #2: Among those receiving benefits, teacher health care costs are slightly higher. In terms of medical care premiums, teacher plans are slightly more expensive, and teachers bear a slightly lower share of their costs than private-sector workers do, but the gaps are not as large as you might expect. Compared to private-sector workers, a higher share of teachers get their full medical premiums paid for (24 versus 15 percent). For single coverage, teachers receive a medical care subsidy from their employers worth about $6,168 per year, or about $961 more than what private-sector workers receive, 18 percent higher. Teachers themselves chip in an average of $1,175 toward annual premiums, compared to $1,384 for private-sector employees.

For family plans, teachers contribute $257 more than non-teachers, school districts contribute about $600 less than private employers, and the total cost of the plans are nearly identical (and actually a couple hundred dollars higher for private-sector workers).

Fact #3: Teachers receive medical coverage for a full calendar year, even though they may only work for 10 months. About 18 percent of teachers earn income from a second or third job to cover their mortgages or other household expenses, but when they seek outside employment, at least they don't need to worry about health care coverage. That is a protection not all workers have.

Adding up all these factors, the average teacher receives health benefits that are much better than employees in other sectors. But those differences are mainly driven by universal coverage, not the generosity of the underlying benefits.

*Throughout this post, I rely on data from the National Compensation Survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For a more detailed overview, read this Education Next piece by Robert Costrell and Jeffrey Dean.In schools across the country, high teacher pension and benefits costs can crowd out other classroom spending. In Washington D.C., pension costs could pump the brakes on Metro services.

A recent GAO report found that, from 2006 to 2017, WMATA’s required employer pension contributions increased an annual average of 18.9 percent -- from $25 million in 2006 to $168 million in 2017. During that same time period, salaries and wages increased only slightly -- an annual average of 1.1 percent. Today, WMATA’s pension system has a $1.1 billion unfunded liability. That’s in addition to $1.8 billion in health care obligations.

The repercussions of this are fairly alarming. Metro Board Chairman Jack Evans told the Washington Post, “In five to 10 years, the amount of money that we have to pay out of the operating budget to fund the pension will be so high that we won’t be able to run the system.”

For their part, the GAO recommends WMATA first develop a comprehensive assessment of their pension plans’ risks, presumably to inform future actions.

The benefits squeeze on current employee wages is mirrored in the teacher workforce. As states funnel more resources toward unpaid pension debts, there’s less funding to increase salaries of existing employees.

Taxonomy:Earlier this week I had the chance to testify in front of a joint committee of the Arkansas State Legislature focused on Public Retirement and Social Security Programs. I used the opportunity to show that Arkansas' current plan offers solid benefits to long-serving veteran teachers, but it can leave 5-, 10-, or even 20-year veterans with insufficient benefits. My full presentation is below.

After defining an "adequate" savings threshold, I compare it to the current Arkansas Teacher Retirement System (ATRS) plan, as well as two other types of plans, a defined contribution plan currently offered to employees at the University of Arkansas and a cash balance plan currently offered to retirees in the ATRS system. As I show in the slides, the current ATRS plan has sufficient contributions going into it, and it does provide adequate benefits to workers who stay in the system for their full career, but that leaves many public school teachers without adequate retirement savings. The majority of Arkansas teachers will need to make up the gap somehow, by saving more in other jobs, working longer, or suffering from a less-than-adequate retirement. In contrast, other types of plans could provide more Arkansas public school teachers with adequate retirement savings regardless of how long they stay.

I also urged Arkansas legislators to focus on questions of benefit adequacy rather than concerns about the plan's effects on teacher recruitment or retention. As we've written before, retirement plans appear to be a poor tool to shape the workforce, and other factors are far more important for how teachers make decisions about whether to enter or remain in the teaching profession. As a result, state leaders should prioritize how well their retirement benefits are meeting the needs of workers. The teaching profession is too large, and too important, to leave without adequate retirement benefits. Click through my full presentation on Arkansas below:

For more info on Arkansas' teacher pension plan, see our review of key data points here or visit the plan's website here.

While I was in Arkansas this week, I estimated that two-thirds of the state's teachers won't work long enough to qualify for adequate retirement benefits. Despite basing my estimates on the state pension plan's own actuarial assumptions, some legislators and audience members pushed back, arguing that the pension plan itself helps keep turnover down. As we've written before, the evidence does not support this argument, at least not for workers of all ages and experience levels. But the Arkansas data provide a few more reasons to doubt how much pension plans affect retention rates.

First, Arkansas teacher retention rates have fluctuated over time, even under the same pension plan. Using the state's own actuarial assumptions (drawn from actuarial reports here)*, I calculated five-year survival rates for teachers. The five-year survival rate is a nice round number, but it's also when teachers "vest" into the Arkansas Teacher Retirement System and first qualify for a retirement benefit. Here are the expected five-year survival rates for teachers at various points in time:

Five-year survival rate for Arkansas teachers, as of 2007: 51 percent

Five-year survival rate for Arkansas teachers, as of 2017: 60 percent

This may be contrary to public perception, but the Arkansas pension system at least is seeing lower rates of turnover than it did 10 years ago. These forecasts are based on historical data and are used in the state's official financial projections. The state's assumed teacher retention rates climbed 9 percentage points (about 17 percent) during the last decade, at a time when the pension plan benefits stayed more or less the same.

Second, as we've noted before, retention rates vary widely across districts, schools, and roles, and Arkansas is no exception. Arkansas doesn't release enough data to dig in too far, but its "teacher" pension plan also includes school support workers, and it disaggregates retention rates specifically for those workers. In contrast to teachers, school support workers in Arkansas have much higher turnover rates. Here are their five-year survival rates:

Five-year survival rate for Arkansas school support workers, as of 2007: 28 percent

Five-year survival rate for Arkansas school support workers, as of 2017: 23 percent

To put a finer point on it, just 23 percent of Arkansas school support workers stay long enough to qualify for any pension at all. They're paying into the pension system, and their employer is contributing on their behalf, but they'll never get anything out of it. Again, the pension plan stayed the exact same throughout this time period, and it was the same pension plan for school support employees as it was for teachers.

Third, I also looked at the assumed retention rates used by the Arkansas Public Employees Retirement System (APERS). In benefit terms, the ATRS and APERS plans are extremely similar, except that APERS covers state and local government employees. For those workers, APERS assumes a five-year survival rate of 27 percent, and it hasn't changed this assumption in the last 10 years.

Now, none of this proves pension plans do or do not have an effect on retention. That would require a much more rigorous study than the superficial look I've presented here. It's possible that pension plans do exert some retention effects on certain groups of teachers, but that those effects are being swamped by other factors like salary or working conditions. But neither of the Arkansas plans assume that workers change their behavior around the vesting period in order to qualify for a pension. And Arkansas' diverging trends do suggest that pension plans are not enough to protect against fluctuations in retention rates over time, or against some groups of workers having much higher or lower retention rates even in the same pension plan.

*Note: Throughout this post, I use the state's turnover estimates for females. The rates for men are even higher.

The following piece originally appeared on The 74.

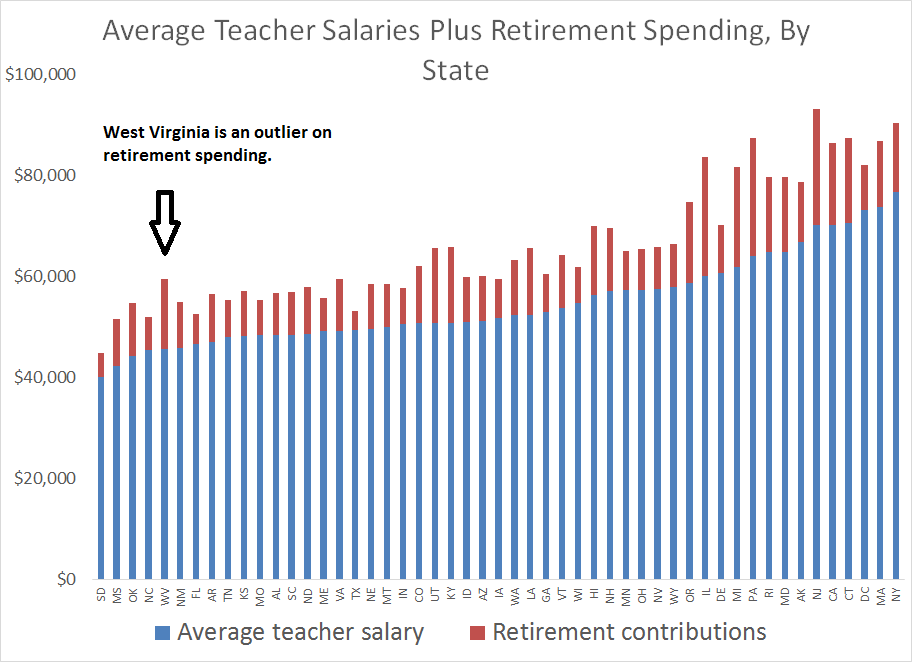

For nine days, West Virginia teachers went out on strike over concerns about salaries and health care benefits.

Much of the press coverage on the strike has focused on West Virginia’s low ranking in average teacher salaries (see examples from The New York Times, USA Today, The Washington Post, CNN, Vox, etc.).

Although it’s true that West Virginia has low average salaries, this statistic misses out on lots of other things. For example, I’ve written before about how growing retirement costs are eating into teacher salaries, and it turns out West Virginia is a prime example of this.

In fact, while West Virginia ranks in the bottom five states in teacher salaries, it ranks in the top five in terms of retirement costs. (Most of that money is going toward paying down unfunded liabilities, but it’s a real expense incurred by the state and its school districts.)

Overall, West Virginia climbs to 32nd in terms of salary plus retirement costs. That’s a very different story than the one being told by the media.

Of course, this also doesn’t get into cost of living.

West Virginia lands in the middle of the pack on cost of living, and if we adjusted the raw salary figures based on how far $1 would go, West Virginia teacher salaries would rank even higher.

None of this is to make a judgment about how much West Virginia teachers should be paid, but that argument shouldn’t hinge on the “average teacher salary” metric.

Without looking at all forms of compensation or adjusting for cost of living, average teacher salary rankings don’t tell us all that much.

Taxonomy:Amidst the strikes and protests about state education funding and teacher pay, the problem of rising benefit costs, such as pensions and healthcare, went largely unnoticed. That’s a mistake because spending on benefits affects how much money gets to the classroom and influences teacher pay.

In a new report, I look into just how much spending on benefits has changed at the district-level between 2005 and 2014. The results are troubling.

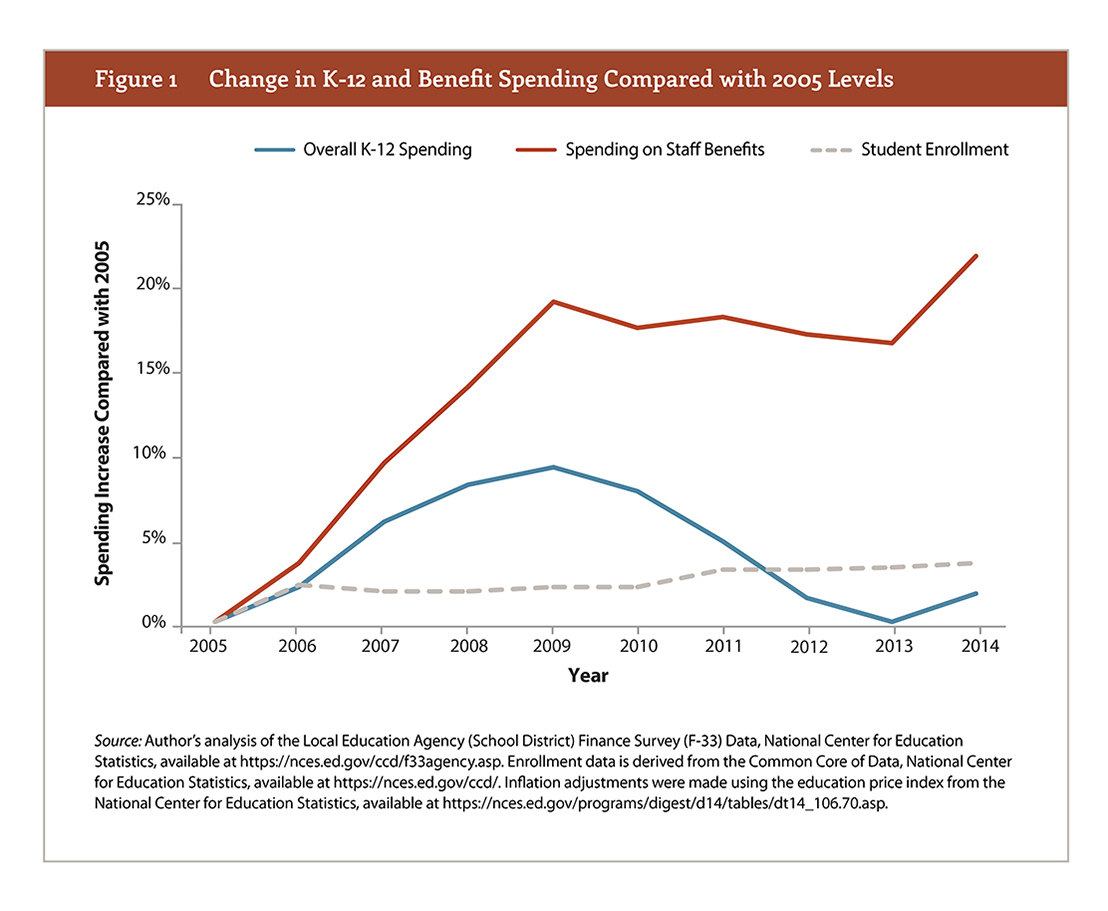

As shown in the graph below, a large part of the problem is that benefit costs are rising at a far faster rate than overall K-12 spending. After adjusting for inflation, nationally we spent just 1.6 percent more on K-12 education generally, but benefit spending increased by 22 percent. The net effect is fewer dollars getting to the classroom. Nationally, benefits consume 19 percent of all K-12 spending. That’s a more than 3 percentage point increase since 2005

The trend of benefits eating up a growing share of K-12 budgets is consistent across the country but varies significantly from state-to-state. In West Virginia, for example, 25 percent of K-12 spending goes to benefits. Once changes to states’ overall investment in K-12 education are taken into account, 23 states actually sent fewer dollars to the classroom in 2014 than they did in 2005 after adjusting for inflation. For instance, North Carolina increased its education budget by 2 percent, but its benefit spending rocketed up by 48 percent. As a result, the state actually sends approximately $589 million less into classrooms.

Rising benefit costs is a problem for educators and policymakers alike. For teachers, much of the rising costs go to pay down debts and thus actually don’t correspond with more valuable pensions or better medical benefits. And worse, without similarly rising overall K-12 spending, fewer dollars are actually spent in the classroom. For state legislatures, the growing benefit costs squeeze budgets. To actually increase K-12 spending, states need to growth their investments more significantly than they have in the past.

This problem likely will get worse before it gets better and should worry educators and legislators alike. There are no easy fixes to these problems, but it will be critical for legislators to find solutions that balance past paying down past obligations with contributing to the education of current students.