Do New York City Teachers Have Adequate Retirement Benefits?

In response to financial pressures, the New York State Assembly has created new, less-generous retirement plans for teachers. Teachers and other education employees are enrolled in one of two plans, the Teachers’ Retirement System of the City of New York (TRS) and the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System (NYSTRS).[1] The benefits are essentially the same in both TRS and NYSTRS, but the finances are kept separate.

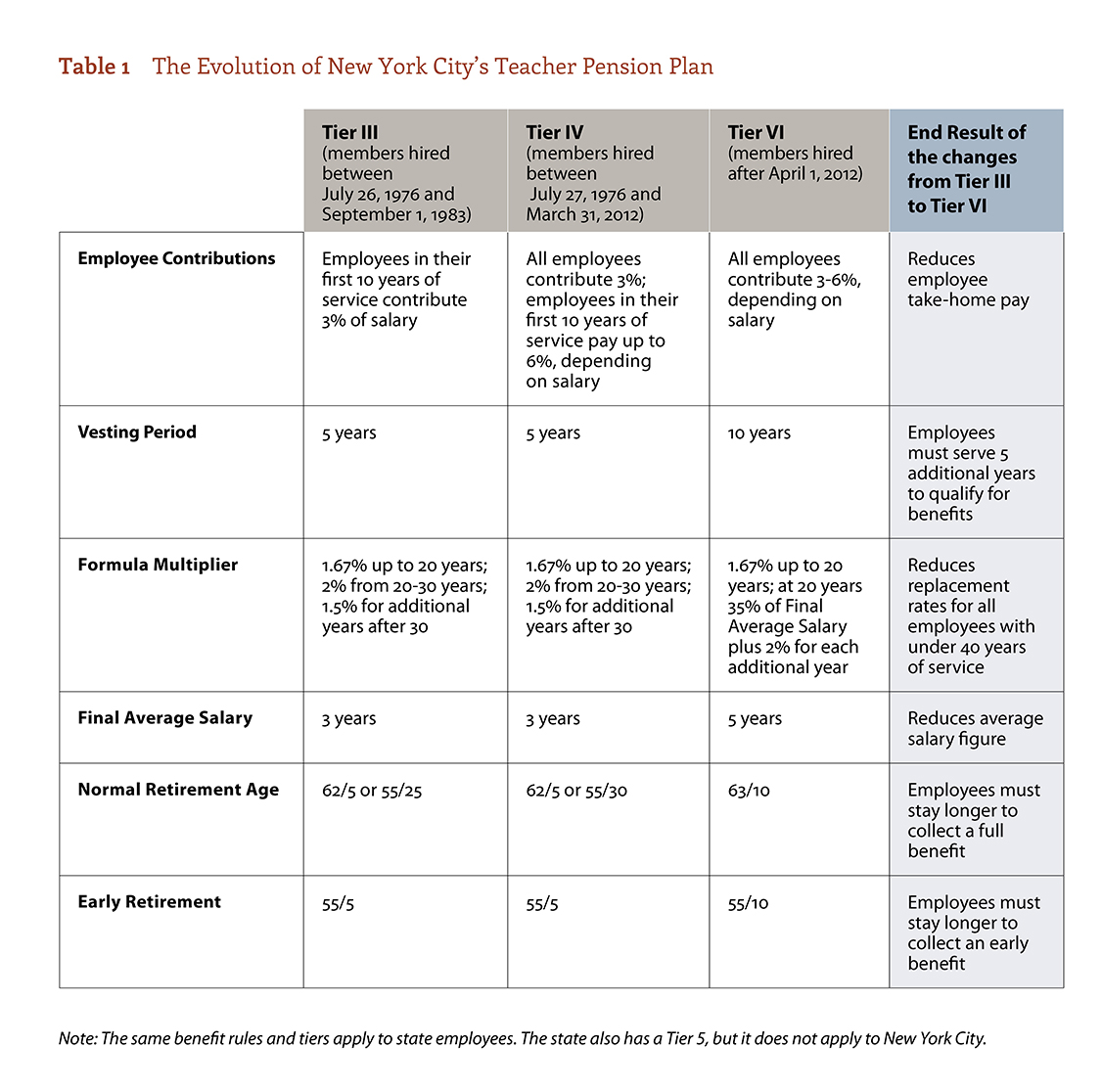

Under both systems, teachers are assigned to a benefit tier depending on their hire date. There are now six tiers, and each tier offers workers less-generous benefits than the one that came before it.

How far have the benefits fallen, and does the current tier (Tier VI) provide sufficient retirement benefits to its members?

In order to answer these questions, this paper begins by outlining a framework for determining whether a given plan’s retirement benefits are “adequate” or not, and then examines whether the TRS plans meet that test. Based on this comparison, it finds that the current Tier VI plan does not provide fully adequate retirement benefits even to the longest-serving veterans. Some portion of teachers will reach at least a minimal adequacy threshold, but the typical teacher would need to serve 23 years before doing so.

New York City teachers, like other workers, can choose to supplement their pension plan with additional personal savings. In particular, New York City teachers can make voluntary, pre-tax contributions to a city-run program designed to encourage such supplemental savings, called the Tax-Deferred Annuity (TDA) program. We find that the TDA program can help more teachers reach the adequacy thresholds, but only if they contribute an additional 7 percent of their take-home pay toward their TDA accounts.

New York has a history of pension reform efforts that preserve the benefit structures for current workers while enrolling new workers in a less-generous benefit tier. As such, this paper concludes with recommendations for how policymakers might do a better job of providing adequate retirement benefits to future teachers. Though not the subject of this paper, policymakers must also consider how they will deliver on the promises made to current teachers and retirees. The alternative models presented here would not save taxpayers money immediately, but they would allow the city to pay down their existing promises while providing a more secure benefit structure to future employees.

(Download a pdf of the full report here.)

II. Defining an Adequacy Standard

The question of how much an individual needs to save for an adequate retirement is a function of four main factors: how long the employee plans to work, how much they save each year, how quickly those investments will grow over time, and their ideal standard of living in retirement. The earlier a worker starts saving, and the longer they plan to work, the lower their annual investment can be. On the opposite end, if workers are not building their nest egg in their early working years, they’ll need to make significantly higher contributions in later years in order to compensate for fewer years of saving and compounding.

Given these factors, many financial experts recommend that workers set aside at least 10 to 15 percent of their annual salaries to invest toward retirement, depending on when they start saving and how long they plan to work.[2] That total includes both employee and employer contributions, and it assumes that Social Security benefits supplement the worker’s personal savings. This generic rule of thumb, which has been endorsed by a range of financial advisers, is designed to help workers know how much they need to put aside each year while they’re working in order to afford a secure and comfortable retirement.

The 10-15 percent contribution rate targets help workers establish specific annual savings targets, and they can help workers understand over the longer term whether they’re on track to a secure retirement or not. For example, experts estimate that someone who starts working at age 25 should strive for their total accumulated savings to surpass their annual salary by age 35. If they keep going, they would accumulate twice their annual salary by age 42, four times their annual salary by age 51, and eight times their annual salary by age 64. Someone saving 15 percent annually would see their assets grow even more quickly.

These are rough targets, and they vary depending on an individual’s personal preferences for retirement and how long they would be expected to live. They are meant more as guidelines than as hard-and-fast rules. Still, they provide a rough approximation of adequate savings, and we’ll return to these targets in subsequent sections.

At first glance, New York City’s pension contribution rates more than pass the adequacy test. Teachers are automatically enrolled in a pension plan (known as the Qualified Pension Plan, or QPP). This is different than the private sector, where individuals are usually responsible for deciding whether or not to enroll in a retirement plan at all, let alone making their own financial contribution and investment decisions. Depending on the teacher’s hire date and salary level, QPP members are required to contribute 3-6 percent of their salary, and the city is contributing an additional 37.7 percent of salary toward the pension plan.

However, a superficial look at contribution rates does not look deep enough when it comes to pension plans like the QPP. For starters, most of that 37.7 percent employer contribution is going toward the plan’s billions of dollars in unfunded liabilities, not to worker benefits. Moreover, individual workers do not receive benefits based on the contributions made into the plan on their behalf. Instead, New York City’s QPP delivers benefits to workers through formulas tied to their years of service and salary. A large body of research has found that these benefit formulas disproportionately reward very long-term employees at the expense of short- and medium-term workers.[3]

In other words, it’s impossible to know whether the QPP is providing adequate retirement benefits without digging deeper into how benefits actually accumulate for workers in the plan. The next section looks at how benefits accumulate under the QPP plan, and then tests those benefits against the same adequacy targets outlined above.

III. How the QPP Plan Works

New York City’s QPP plan operates like other traditional pension plans. The state defines the benefit formula and the plan administrators determine the investments and annual contributions necessary to pay for benefits to be paid in the future. Employers and employees share the responsibility for making contributions. Benefits are based upon a formula tied to salaries and years of experience, and are not directly tied to any individual’s personal contributions. The benefit formula for workers hired after the year 2012, Tier VI, consists of a multiplier (1.67 percent for the employee’s first 20 years, and then increasing after that) multiplied by the worker’s final average salary and years of service. For example, a member with 10 years of service qualifies for a pension worth 16.7 percent of their current salary (that is, 1.67 percent times 10 years of service), payable upon reaching the state’s normal retirement age. For future retirees, they can begin to collect their benefits upon reaching age 63 if they have ten or more years of service.

New York has made a number of changes to the QPP in recent years (see Table 1: The Evolution of New York’s Teacher Pension Plan). Compared to prior generations, members hired after 2012 will pay higher contribution rates than their predecessors (aka they will earn less in take-home pay), they’ll have to serve longer to qualify for any retirement benefit at all, and they’ll receive lower pension benefits when they retire.

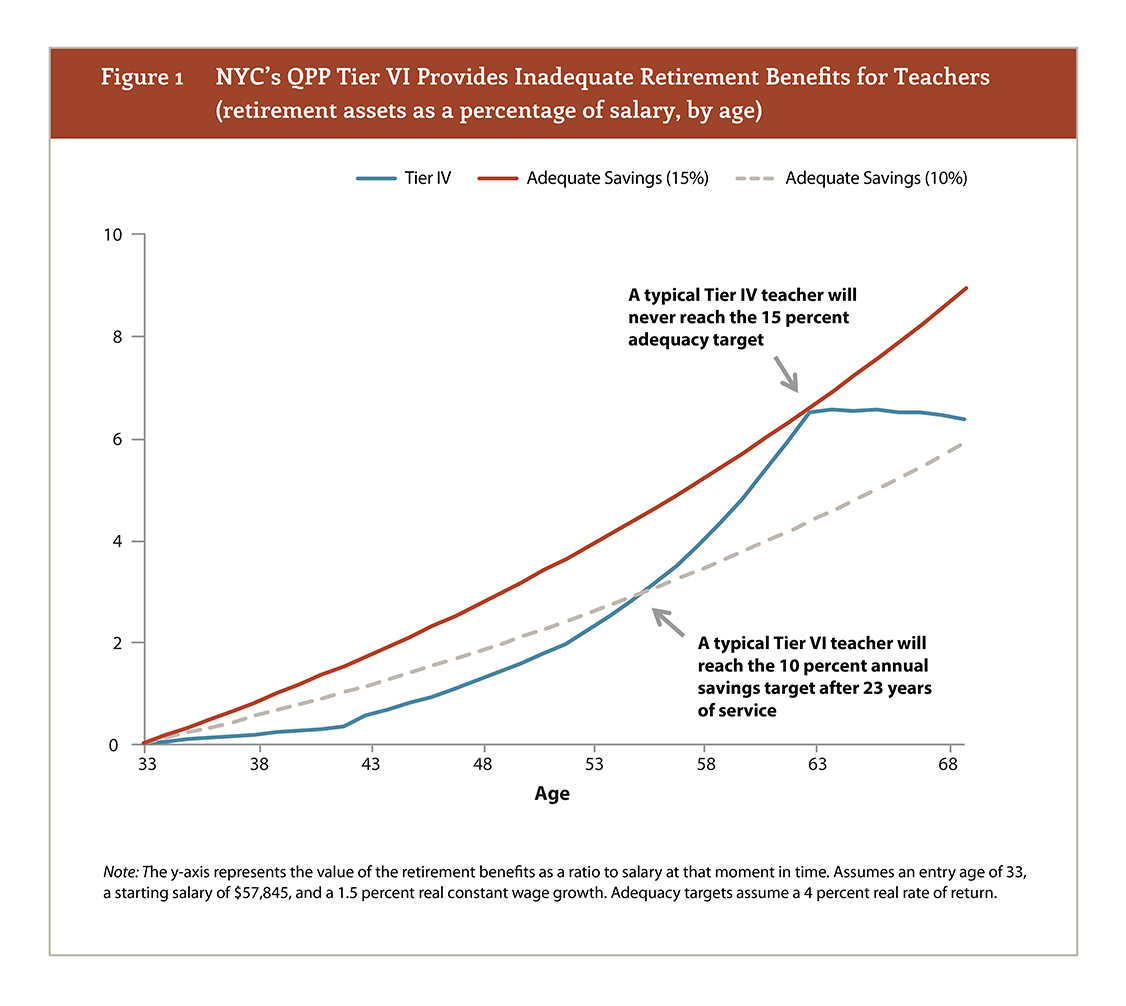

How do these rules translate into benefits? Figure 1 below shows how benefits would accumulate for a typical teacher enrolled in Tier VI of the QPP plan. The blue line shows how QPP benefits grow over time for a new, 33-year-old teacher (See Appendix Table 1 of the full report for the assumptions used here). We’ve chosen 33-year-old entrants as a representative given the plan’s average membership age and average years of service.[4] The actual shape of the line for any given worker would depend on the age at which they entered the plan. Workers who entered the QPP plan at younger ages would face an even more back-loaded curve and an even harder time reaching adequate savings targets. Workers who entered the plan at older ages would have a faster accumulation rate, given their comparative proximity to the plan’s normal retirement age.

The dashed red lines in Figure 1 represent the adequacy levels recommended by financial experts, the annual savings targets of 10 to 15 percent of salaries. The y-axis is the value of the retirement benefits as a ratio to the current salary. As the graph suggests, for the first 23 years of service, teachers in Tier VI have retirement benefits that are worth less than even the lower 10 percent adequacy band. If the teacher leaves the QPP plan prior to that point due to relocation, career change, or other reasons, she will be below even the minimal level of benefits that most experts recommend. However, if she remains, her benefits will accrue rapidly and would almost, but not quite, reach the upper adequacy band upon reaching normal retirement age. At that age, our hypothetical teacher would have worked 30 consecutive years in New York City public schools. This is the effect of the back-loaded formula. It requires teachers to remain for very long stretches of time in order to qualify for adequate retirement benefits.

Needless to say, most New York City teachers do not remain in the QPP plan long enough to qualify for adequate retirement benefits. Based on the latest citywide data, less than half of New York City’s teachers remain in the district in any capacity for even 10 years.[5] In other words, given Tier VI’s 10-year vesting period, less than half of its members can even expect to qualify for any retirement benefits at all.

To be clear, even the previous pension tier, Tier IV, had similar problems. It too failed to provide most teachers with adequate retirement benefits. Tier IV members can expect to reach the minimal adequacy target after 19 years of service (as compared to 23 under Tier VI), and can expect to reach fully adequate retirement benefits after 27 years of service. Between Tiers IV and VI, they cover 99.5 percent of active New York City educators (the remainder are in Tiers 1-3).

In both of these tiers, the benefit structure does a good job protecting very long-term employees, but it does so at the expense of everyone else. Some readers might think retirement plans should be designed in this way, to counter against teachers who might otherwise leave mid-career. However, the evidence suggests it is a mistake to look at pension plans as an effective retention tool.[6] Instead, employers should design retirement plans to meet the retirement savings needs of workers, not as a retention tool for employers.

IV. What’s Driving the Benefit Changes

Why has New York created new tiers of benefits? The short answer is policymakers have been trying to reduce overall costs as the contribution requirements to pay down the pension debt on previous tiers kept growing.

To understand the full rationale for those decisions, it’s helpful to break down how actuaries estimate pension plan costs. They divide pension spending into two components. The first is called the plan’s “normal cost,” which measures how much the plan’s benefits are worth, calculated as an average across all members in the plan. To come up with this number, actuaries must make assumptions around salary growth and retention rates, and they also estimate longevity to determine how long retirees will eventually collect their benefits in retirement. The New York City QPP plan has an average normal cost of approximately 13.3 percent of salary.[7] That represents the plan’s best estimates for how much the benefits earned by workers in a given year cost, on average across all members and all tiers. As discussed above, no individual member will ever actually receive that 13.3 percent normal cost; some members will get more than that, while many will receive much less. Those members placed in the newer tiers will get even less.

Pension plans like the QPP sometimes carry another expense, the cost of paying down any accumulated unfunded liabilities. Each year, pension plans accumulate liabilities as they make promises to pay future benefits. If contribution rates match the plan’s normal cost, and if all of the plan’s assumptions on salary, retention, investment returns, inflation, etc. are all correct, the plan is said to be 100 percent funded. In that case, the plan’s expected assets would fully match their expected liabilities.

New York City’s QPP plan, however, has not been fully funded at any point in at least the last two decades.[8] As of 2019, it had made $69.6 billion in promises to teachers and retirees, but the actuarial value of its assets — meaning the amount of money it had on hand plus its expectation for how that money would grow over time — totaled only $44.4 billion. To make up that difference and pay off that debt over time, the QPP actuaries estimate it owes an additional 24.4 percent of every participant’s salary.

Between the plan’s normal cost and the cost of paying down its unfunded liabilities, New York City is currently contributing 37.7 percent of each teacher’s salary toward TRS. This level of contributions makes New York City an outlier nationally. In total, if New York City were considered a state, it would have the highest teacher retirement costs in the country.[9]

From a worker’s perspective, their pension plan’s unfunded liability costs may only filter down to them indirectly, through lower salaries, higher employee contributions, or reduced spending on other school services. After all, the actual benefit formula in defined benefit plans like the QPP carries no investment risk for workers and, if they continue in the plan until retirement, they are guaranteed a stream of income. When the state has introduced new tiers, it has always protected existing workers’ ability to continue accruing benefits as promised. For the newest generation of teachers, however, not to mention short- and medium-term teachers, geographically mobile teachers, or career switchers, being in a defined benefit plan brings a different set of risks.[10] If teachers move across state lines or change careers, they can either withdraw their contributions or wait to draw a pension. Either way, this translates to inadequate savings rates for workers.

V. How the TDA Plan Helps Teachers

New York City teachers, like other workers, can choose to supplement their employer-provided QPP plan with their own personal savings. The city itself, in fact, offers workers a voluntary retirement plan called the Tax-Deferred Annuity (TDA) program. The TDA program functions as a mix of a pension and a defined contribution plan like a 401(k). Workers can choose how much to contribute, up to maximum limits set by the federal government. Unlike most retirement savings accounts like a 401(k) or an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) where workers are subject to the whims of the market, the TDA plan guarantees participants at least a 7 percent return on their investments. When the worker is ready to retire, they can convert their balance into an annuity that pays out monthly benefits for life, just like the QPP and other traditional pension plans.

Although not pictured, we find that the TDA program goes a long way toward helping teachers reach the adequate savings targets. However, that requires teachers to voluntarily participate in the TDA plan in the first place. And, due to how inadequate the QPP benefits are for most workers, they would need to make significant contributions toward the TDA plan to reach the adequacy thresholds. For example, our hypothetical worker could meet at least the minimal adequacy target no matter how long they stayed if they participated in both the QPP and the TDA, but only if they set their voluntary TDA contributions equal to 7 percent of their take-home pay in addition to their required contributions under the QPP.

For teachers with inadequate retirement savings during their years of teaching, they’ll need to increase their savings rate later in their career, work longer, rely more on family or governmental support, or live a more modest lifestyle in retirement. Despite benefit cuts in recent years, the current Tier VI of New York City’s QPP plan is still providing retirement security for a small subset of long-term teachers, but it does not do a good job covering all members within the system. The next section suggests alternative plan designs that would do a better job of providing all teachers with adequate retirement benefits.

VI. How to Provide All New York City Teachers with Adequate Retirement Savings

Much of the public debate over teacher pensions is framed as an either/or: Either states and cities keep their current defined benefit pension plans, or they move all workers to low-cost 401(k)-style defined contribution plans like in the private sector. But this is a false dichotomy. There are alternatives that could do a better job of providing all teachers with retirement security than the QPP plan does today.

Option 1: Improve the Pension Plan

The first option would be reforming the QPP itself. New York could choose to boost benefits to early- and mid-career teachers by adjusting its rules on the refunds it provides to departing teachers. Currently, teachers who withdraw from the QPP system are able to claim a refund on their own contributions, with 5 percent interest, but they are not eligible for any of their employer’s contributions, regardless of whether or not they are vested. Without any employer match, the only way for a New York City teacher to reach the adequacy threshold would be for them to increase their contribution rates into either the QPP plan or the voluntary TDA.

Alternatively, New York could create a new Tier VII under the QPP with a much smoother benefit accrual. Increasing the normal retirement age while lengthening the period over which an employee’s salary is averaged, and introducing a benefit cap could make it possible to increase the benefit multiplier without increasing overall costs. Combined, these sorts of changes could dramatically increase the share of workers who would receive adequate benefits. While still a defined benefit pension plan, this type of design would deliberately trade away some back-end rewards in order to increase the chances that all entering teachers would leave their years of service with adequate retirement benefits.

Option 2: Make a Version of the TDA the Primary Retirement Plan

A second option would be for New York to build on the positive features that already exist in the TDA plan. Rather than keeping the TDA as an optional, side benefit, the city could expand the TDA to become the default retirement option for all new teachers.

That would require two key changes. First, the city is currently guaranteeing TDA members a 7 percent return on their investments. That is higher than most financial experts predict for future returns, and it means the promises made under the TDA are contributing to the city’s larger pension funding problems. Indeed, when other state and local governments offer their own versions of the TDA plan — often referred to as “cash balance” or “guaranteed return” plans — they set the guarantee at a more moderate level.

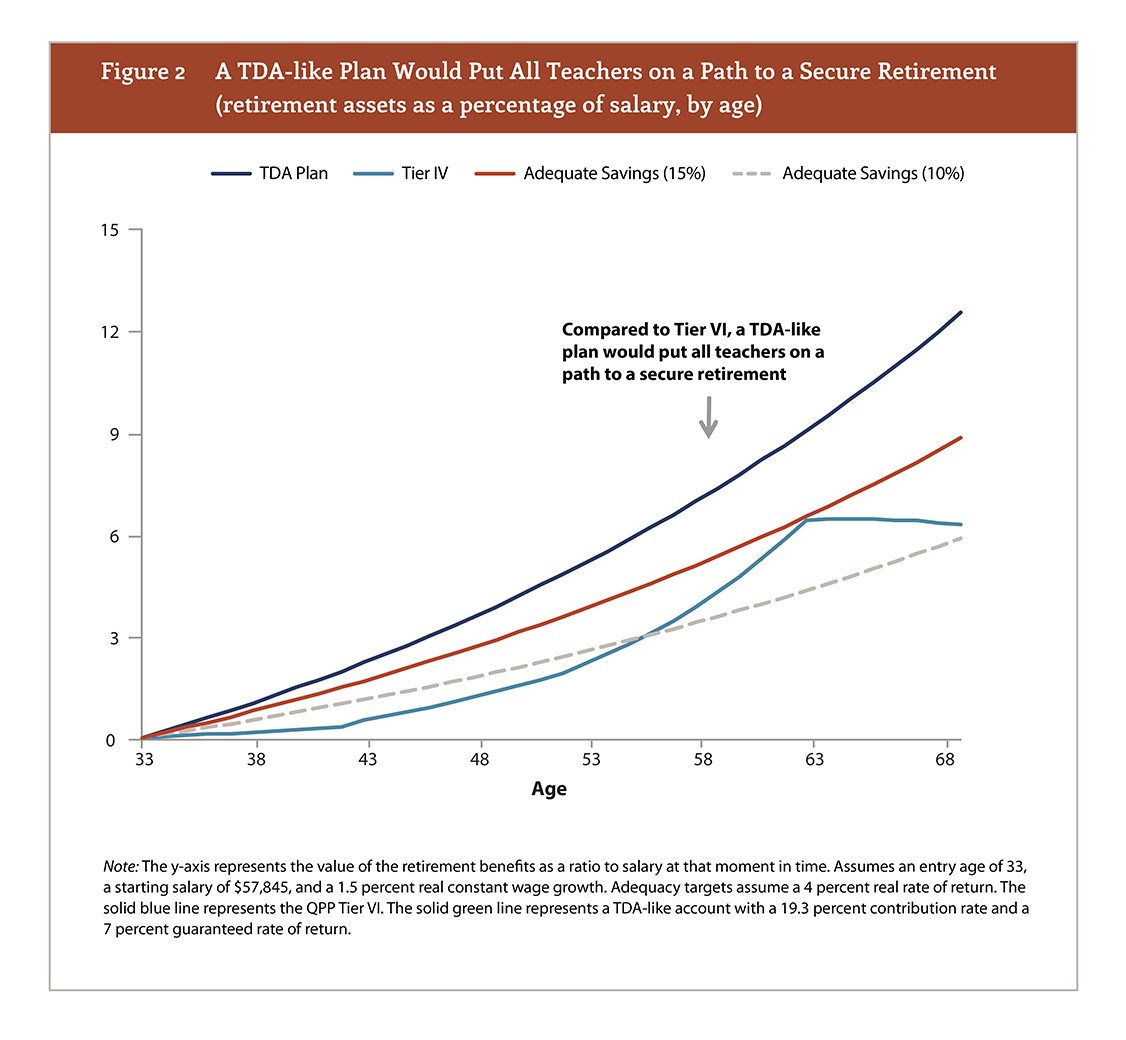

Second, to make the TDA a true retirement savings vehicle, the city would have to start making direct contributions toward it. Believe it or not, there is money to do this. As described above, the city is already paying 37.7 percent of each teacher’s salary toward the entire TRS system. But only one-third of that amount went toward worker benefits (the 13.3 percent normal cost). The rest went toward paying off the system’s unfunded liabilities.

That is, the city could afford to pay the same 13.3 percent of salary toward worker benefits as their contributions toward teacher TDA accounts, while still making the same contributions to pay down the system’s unfunded liabilities. As Figure 2 shows below, teachers would be better off taking their retirement contributions this way than they are through the current QPP Tier VI plan. The chart is the same as Figure 1 but with two changes. One, it adds the solid green line representing a hypothetical TDA-like account. And two, the y-axis had to increase to accommodate the higher assets accumulated under the TDA-style plan. That is, with the same employer and employee contributions it is making now, New York City could afford to put all of its teachers on a path to a secure retirement if it let its contributions flow to TDA-like accounts rather than the current QPP arrangement.

Guaranteed return plans like what we’re proposing here are increasingly common in the private sector, with millions of members nationwide.[11] A number of state and local governments have already made the switch to a TDA-like plan. Nebraska state employees, Texas county and municipal workers, and Kansas teachers are all enrolled in a similar version. Those plans all offer a lower rate of return than what the TDA currently guarantees, but New York City could lower its promise under the TDA by 2 percentage points, to a 5 percent guarantee, and still provide all workers with adequate retirement benefits.

Option 3: Give Teachers Options Over Their Primary Retirement Plan

Even if expanding the TDA is a step too far, New York legislators could at least give public school teachers the same options as it does to other public employees. At the same time New York created Tier VI in the QPP plan for teachers, state legislators also created a “Voluntary Defined Contribution” as an option for non-unionized employees. (The state already offers higher education employees in the CUNY and SUNY systems the option to join a defined contribution plan.) Both the VDC plan and the defined contribution plans offered to CUNY and SUNY employees allow members to qualify for retirement benefits after just one year of service, compared to ten under Tier VI of the QPP.

Giving teachers the same retirement plan options as the state provides other public-sector workers would be better than forcing them all into the QPP plan, where only the fortunate few will earn an adequate retirement benefit. Such a change could keep contributions constant and preserve the benefits promised to current and future retirees, while simultaneously putting all new teachers on a better path to a secure retirement.

(Download a pdf of the full report here.)

[1] Although these plans are referred to as “teacher” retirement plans, TRS and NYSTRS both include a range of different types of workers employed by school districts, state colleges and universities, charter schools, and other educational institutions. This brief uses the terms “teachers,” “members,” or “employees” interchangeably, but they are meant to apply to all participants.

[2] See, for example, Alicia H. Munnell, Francesca Golub-Sass, and Anthony Webb, “How Much to Save for a Secure Retirement,” research brief, Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, November 2011, http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/IB_11-13-508.pdf, and “How Much Do I Need to Retire?,” Fidelity Viewpoints, August 21, 2018, https://www.fidelity.com/viewpoints/retirement/how-much-money-do-i-need-to-retire.

[3] See, for example: Robert Costrell and Michael Podgursky, “Peaks, Cliffs, and Valleys: The Peculiar Incentives in Teacher Retirement Systems and Their Consequences for School Staffing,” Education Finance and Policy 4, no. 2 (2009): 175–211; Martin Lueken, “(No) Money in the Bank: Which Retirement Systems Penalize New Teachers?,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute, Washington, DC, 2017; Josh McGee and Marcus Winters, Better Pay, Fairer Pensions III—The Impact of Cash-Balance Pensions on Teacher Retention and Quality: Results of a Simulation, Report 15 (New York: Manhattan Institute, 2016); Ben Backes et al., “Benefit or Burden? On the Intergenerational Inequity of Teacher Pension Plans,” Educational Researcher 45, no. 6 (2016): 367–377.

[4] Table XII-3 of the TRSNYC FY19 Actuarial Valuation report, https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/actuary/downloads/pdf/TRS_Fiscal_Year_2019_Actuarial_Valuation_Report.pdf.

[5] Independent Budget Office of the City of New York, “Teachers: Demographics, Work History, Training, and Characteristics of Their Schools,” Human Resources: Traditional Public Schools in NYC, 2017.

[6] For an overview of the research literature on how pensions affect teacher behavior, see: https://www.teacherpensions.org/blog/teacher-pensions-recruitment-and-retention.

[7] Although TRS does not release this figure in percentage terms, I was able to estimate it using the plan’s reported $1.3 billion contribution toward normal costs, as a percentage of the plan’s total $3.7 billion in total contributions.

[8] Public Plans Data, “New York City Teachers,” https://publicplansdata.org/quick-facts/by-pension-plan/plan/?ppd_id=77.

[9] Author’s analysis of data from: Public Plans Data, https://publicplansdata.org/public-plans-database/.

[10] Josh McGee and Marcus Winters, Better Pay, Fairer Pensions II: Modeling Preferences Between Defined-Benefit Teacher Compensation Plan, (New York: Manhattan Institute, 2014)

[11] For example, the Kravitz company used Department of Labor data to estimate there were 11.8 million workers covered by a cash balance plan as of 2016. See: 2018 National Cash Balance Research Report, 10th Annual Edition (Los Angeles: Kravitz, 2018), https://www.cashbalancedesign.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/NationalCashBalanceResearchReport2018.pdf.