All defined benefit pension plans make assumptions. They need to estimate how much money they’ll need in order to pay the benefits they’ve promised in the future. That requires them to calculate things like how much money they should save today, how fast that money will grow, and how long employees will live into retirement. Pension plans also need to estimate how many employees will qualify for a benefit in the first place.

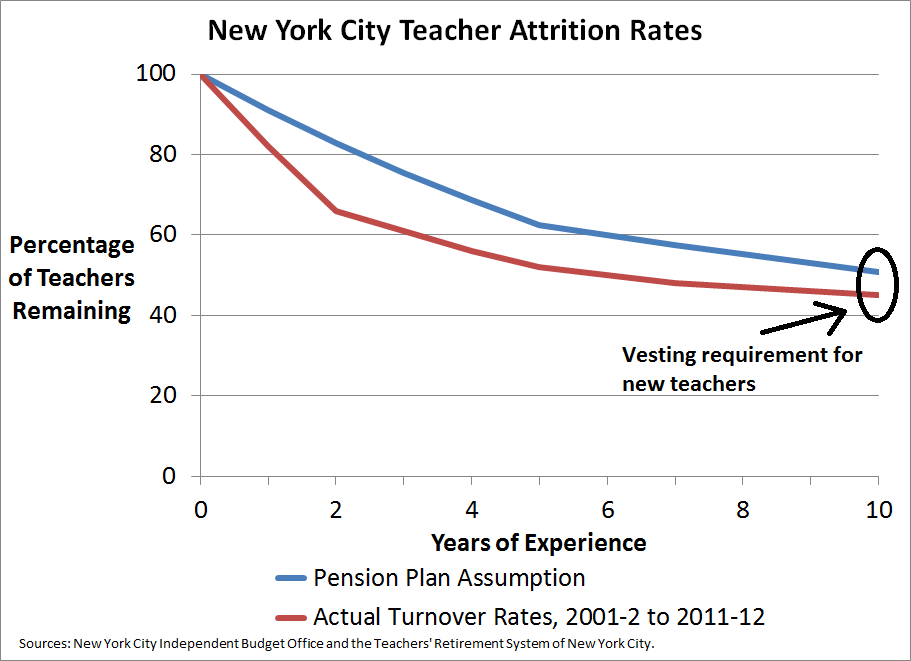

In order to determine how accurate those assumptions are, I looked at the assumed and actual teacher turnover rates in New York City. The chart below shows the results. The blue line represents the plan’s assumptions, which I gathered from the Teachers’ Retirement System of the City of New York’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report. The red line shows the actual attrition rates as calculated by the New York City Independent Budget Office for the 9,437 teachers who began teaching in New York City in the 2001-2 school year, the most recent time period for which we have 10 years of data.

I focused on the ten-year survival rate for a reason. In order to cut costs and recover from the recent recession, New York City recently lengthened the vesting requirement, the time period employees need to stay in order to qualify for even a minimum pension, from five years to ten. The lines above show the consequences of this decision. Regardless of whether I use the pension plan assumptions or the actual turnover rate, the lines show that half of all new teachers will not reach ten years of service and will not qualify for a retirement benefit.

These teachers—remember, we’re talking about thousands of individuals a year—are eligible for a refund of their own contributions and 5 percent interest. They are NOT eligible for the full 7 percent return that the plan assumes it can earn on its investments, and they are NOT eligible for any part of their employer’s contribution. This is a significant amount of money in New York City. Last year, for every $1 the city paid in teacher salaries, it put $0.36455 into the city’s pension plan. Teachers who leave before qualifying for a pension forfeit this entire amount. A beginning teacher with a bachelor’s degree in New York City earned $45,530 in salary last year, meaning the city contributed $16,597.96 on their behalf into the pension plan. But if the teacher leaves before ten years, they get none of this money; the employer contributions stay in the pension plan to supplement the retirement of those who remain.

A recent report looked at whether we could change this situation by shifting away from traditional defined benefit systems and offering more compensation in the form of base salaries rather than benefits. It found that these cost-neutral changes would allow New York City to increase total teacher compensation including salary and benefits for the vast majority of teachers.

In education policy, we often talk about “teacher turnover” as a problem for schools, employers, and communities. In doing so, we forget about the affected individuals. As in Washington, D.C., the New York data shows that the consequences of teacher turnover are extremely high for individual teachers, the thousands who leave the profession every year.