Americans are not very good at saving money. The Wall Street Journal reported last week that adults under age 35 have a savings rate of negative 2 percent, meaning they're actually taking on debt in order finance their current consumption.

For most people, public policies are not to blame for their lack of saving. Individuals decide their own spending or saving habits, and they decide whether or not to participate in their employer’s retirement benefits, how much to save, and how to invest. Public policies set tax exempt savings limits and basic rules for individuals, but ultimately, individuals must make their own decisions.

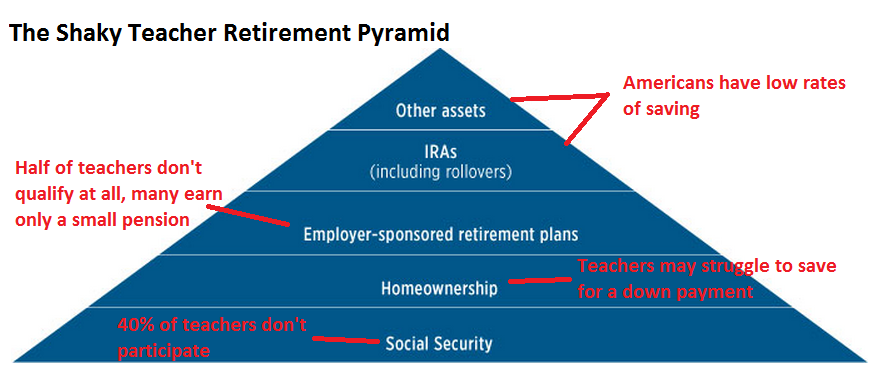

For teachers, however, insufficient savings can be blamed on bad public policy. To show how these policies harm individual teachers, I crudely annotated the Investment Company FactBook's Retirement Resource Pyramid.

At the base of the retirement pyramid for most workers is Social Security. For middle-income workers like teaches, Social Security may represent 40 percent of their retirement income. Unfortunately, 1.2 million K-12 teachers are not enrolled in Social Security, including a substantial portion of teachers in 15 states—Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Texas. These teachers are particularly vulnerable without the base of retirement security that Social Security affords all other American workers.

Next comes homeownership. For many households nearing retirement, their homes may be one of their most significant retirement assets. While we don't have national data on homeownership rates for teachers, we do know the average teacher salary is nearly in line with the median household income. Since teachers may be married or have other sources of income, we can assume they have slightly higher rates of homeownership than the 64 percent nationwide. Still, this would require them to be able to set aside enough spare income over their working years to save enough for a down payment, something that wouldn't be easy in every part of the country on an entry-level teacher salary.

Employer-sponsored retirement plans are the next-largest source of income for retirees. For teachers, that mostly means their state-provided pension plan. But current teacher pension plans are not meeting the needs of today's workforce. Half of all new teachers won't qualify for a pension at all, and many more will qualify for a pension that's worth less than their own contributions. A small minority of teachers will receive a fairly substantial pension, but, contrary to popular perception, most will leave their service with very little retirement savings.

At the top of the retirement savings pyramid are individual contributions to accounts like 401(k)s, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), or other savings vehicles. If we assume that teachers have the same savings rates as others at their income level, they are likely to have nothing or very little set aside in the way of personal retirement savings.

The end result is a pretty shaky retirement pyramid for teachers. At 3.3 million, public school teachers are one of our largest professions, and their retirement savings is our collective responsibility. We might hope that individuals will suddenly start to develop better saving habits, or we could start developing better public policies to support them.