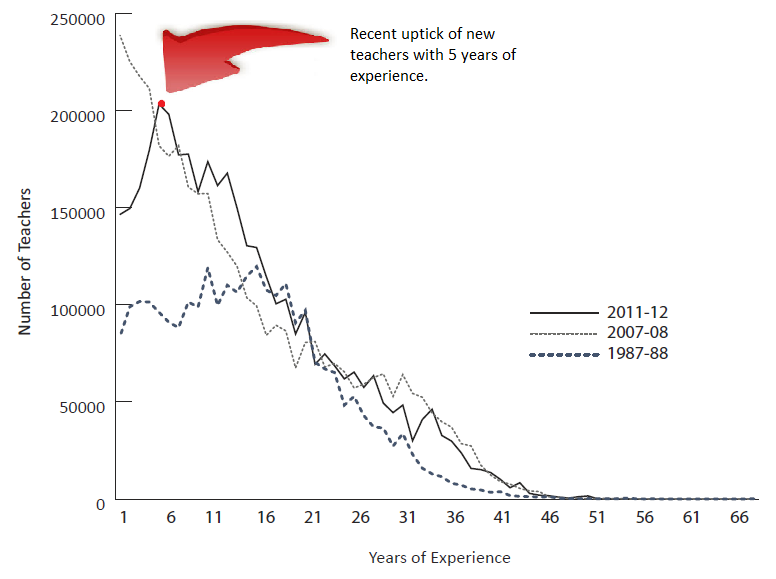

There’s some good news for schools and teachers from the Center for American Progress (CAP): more new teachers are staying in the classroom after five years, up nearly 20 percentage points since 2007. The new finding uses data found in the 2007-08 and 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey, the Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Study, and 2012-13 follow-up study of the 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey released last fall. CAP found that 87 percent of new teachers stayed in the profession for at least three years, and close to 70 percent of new teachers stayed for at least 5 years.

Within the larger picture of teacher retention, it’s not clear whether these increases though are here to stay. The Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE) has tracked the teacher workforce over the course of several decades. CPRE finds a general trend of fewer years in the classroom overall, but with a recent uptick in longevity after the economic downturn. During the depths of the recession, employers stopped hiring and few people left their employment voluntarily. That was true across the broader economy, and it’s showing up in rising teacher retention rates.

What’s less clear is how this recent trend fits in with a longer-term picture. In 1988, if you asked a teacher how many years of experience he or she had, the most common answer was 15 years. By 2008, the most common answer to the same question would have been one year, followed by two years. By 2012, this figure had crept up to five years. As the CAP report indicates, retention is higher and more teachers are deciding to stay into their fifth year. Time will tell whether this recent increase is just an effect of the recession or part of a larger structural change.

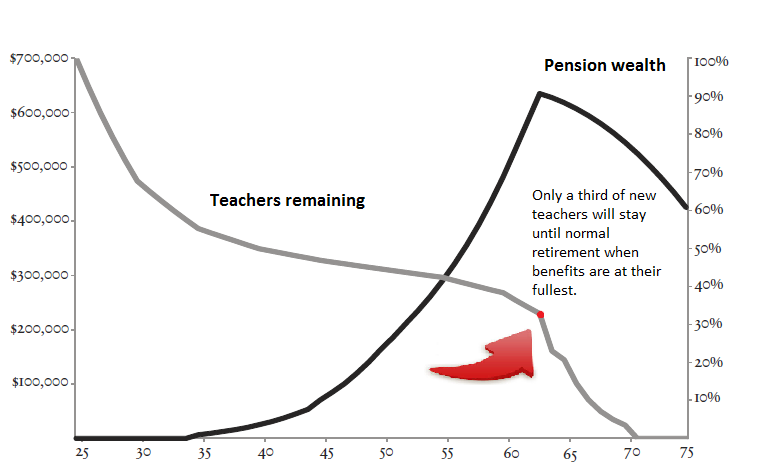

Teacher Classroom Teaching Experience, 1987 – 2012

Source: Richard Ingersoll, Lisa Merril, and Daniel Stuckey, “Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force,” University of Pennsylvania, April 2014.

But one thing is clear: despite this recent uptick, teachers who stick around for a fifth year still aren't going to be rewarded with a generous pension. In order to qualify for a pension, teachers must meet certain service or vesting requirements. Most states require a minimum of five years; 17 require teachers to work at least 10 years. Teachers who stay for a fifth year but then leave before year 10 would still miss out on qualifying for a minimum benefit in these states, despite their extra years of service (they would just receive a refund on their contributions and posssibly interest for each year). Even teachers who do qualify for a pension after just five years aren’t likely to see much in benefits because benefits are heavily backloaded. Rising retention means more teachers will qualify for some level of a pension, but it still won’t be very large and will actually cost the state more money.

Teachers accrue very little during the first couple of decades of teaching. It’s not until they get closer to their plan’s normal retirement age—usually after 30 years or more for a 25-year-old teacher—that teachers begin to rapidly accrue benefits. The graph below comes from a paper by Josh McGee and Marcus Winters and shows the percentage of New York City teachers who stay in the classroom over the years and their corresponding pension wealth.

New York City Teacher Retention & Pension Wealth

Source: Josh McGee and Marcus Winters, “Modernizing Teacher Pensions," National Affairs, January 2015.

The gray teacher retention line begins high and drops significantly within the first ten years and continues to decline as time passes as fewer teachers stay in the classroom. Meanwhile, the black pension wealth line begins very low within the first two decades and quickly picks up more pension wealth as a teacher near retirement at age 63 and teaches beyond 30 years. A teacher earns roughly $3,500 per year of work for the first 20 years of service and then $30,000 per year for teaching years 30 through 38.

But only a third of new teachers will remain long enough to actually receive full retirement benefits. Also, New York City has a 10 year vesting requirement for any teacher hired after 2012. This means that even if a New York City teacher stays in teaching until her fifth year but leaves before year 10, she forfeits any rights to a pension benefit. Her retirement wealth will be relatively meager even if she stays beyond 10 years but leaves before 20 years.

It’s a good thing that teachers are staying in the classroom into their fifth year. States should reward teachers for making these choices. Alternative plans, such as a cash balance, accrue benefits smoothly and are not back-loaded. Rather than continuing blunt systems that only reward a small minority of teachers while leaving the majority of teachers with inadequate benefits, state and local plans should consider offering plans that more evenly distribute benefits.