Pension cuts stir up a lot of controversy, and most recently, Illinois’s Supreme Court rejected the state’s attempt to reduce benefits. Core to the debate was an often overlooked, but powerful policy lever: cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs). COLA’s are just one small mechanism for adjusting pensions, but they can have a big impact on worker benefits over time.

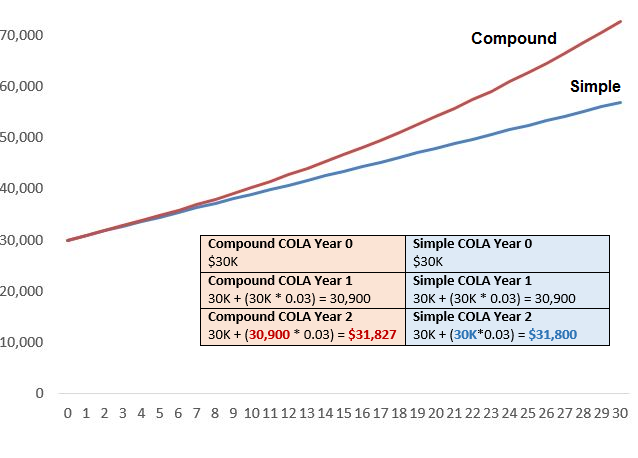

Take for example a retired teacher in Illinois. In the 1980s, state teachers were eligible for a simple, uncompounded, 3 percent increase to ensure their benefits kept up with inflation. In 1989, however, the state passed legislation allowing retired teachers to grow at 3 percent, compounded over time. While this may seem like a minor change, it materially affected retired teachers’ welfare and the state’s coffers. For a teacher who retires at age 60 with a starting pension benefit worth $30,000, her pension grows to $39,000 when she reaches age 70 under a simple COLA, but rises to over $40,300 under the new compound COLA. That same teacher’s benefits grows to $48,000 when the teacher turns age 80 under a simple COLA increase, but rises to over $54,000 under the new compound COLA. Simple interest only adds a fixed amount of interest based on the initial pension benefits. But compound interest grows “interest on interest,” growing from the amount of each prior year.

The Power of Compound Interest:

A Retired Illinois Teacher’s Pension Benefits

The purpose of a COLA is to adjust benefits for inflation. Thirty-thousand dollars today won’t buy the same things as $30,000 in the future. But compared to neighboring states, Illinois’ fixed 3 percent compounded rate is on the more generous side. Indiana, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Michigan only provide COLAs on an ad hoc basis, or make COLA decisions based on investment returns. Missouri and Kentucky, neither of which offer Social Security to its members (like Illinois), provides a COLA equal to the change in the Consumer Price Index, capped at 2 percent and 1.5 percent respectively. Social Security, which automatically adjust benefits for inflation each year, set its adjustment for this year at 1.7 percent.

Ideally, COLAs should be pegged to inflation to preserve benefits for retirees, like Social Security, but at the same time shouldn’t increase any faster. Illinois’ fixed compounded COLA outpaces inflation, but the state can’t change what it’s already passed. In 2011, the Illinois legislature tried scaling the COLA back to where it had been—a simple 3 percent —but the state Supreme Court ruled that doing so would impair benefits. A lower court rejected a Chicago pension reform law that would have also reduced COLAs for municipal workers for the same reason. One report estimates that the increased COLA benefits across all the state’s five retirement systems (not including Chicago) resulted in $1.3 billion in increased debt since the change.

While COLAs may just seem like an obscure, minor technical change, moving COLAs up or down have real consequences for teachers and states.