Millennials are an easy target, and it’s easy to assume shifts in worker turnover are the result of this generation’s restlessness. But this is a misconception, and once we examine tenure data by age group and generation it reveals that millennials are merely following a broader downward trend in job tenure. Over the long term, millennials are following similar patterns as the generations that came before them.

First, as with any good myth, there's a kernel of truth. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that the median time workers have been with their current employer is 4.6 years, up slightly from ten years ago. This data seems to show that, contrary to popular perception, workers are actually staying in their jobs longer than they were in previous years. The New Yorker’s Mark Gimein recently commented on the increase: “our collective nostalgia misrepresents historical job security so completely that it gets it close to backward.”

But wait, the averages here are misleading us from some bigger, underlying trends. We shouldn't be comparing today's average with yesterday's; we should be looking at how tenure changed for groups of workers at various stages of their careers.

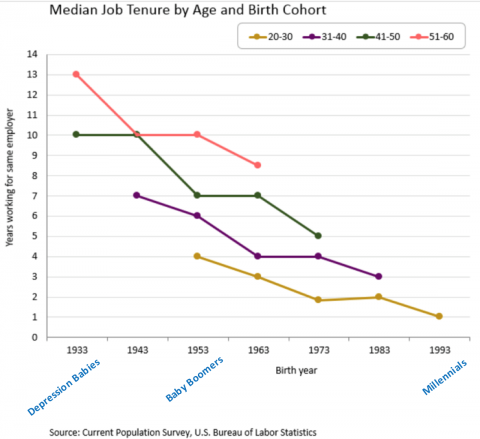

We know that older workers tend to have longer tenures with their current employers than younger workers do. This has been true across generations, so what’s critical is looking at how today’s older workers compare to older workers in the past and how today’s younger workers compare to younger workers in the past. Once we take a closer look and sort the data properly, the data confirms the popular perception: job tenure is indeed declining across all age groups. Rather than being an entirely new phenomenon, the mobility of the millennial generation is best seen as merely one part of a greater downward trend.

To show this, the Atlanta Fed disaggregated the job tenure data and organized it by age and birth cohort instead of calendar year. Their graph, reproduced below, tells this more accurate story.

When the first group of baby boomers were in their thirties, they had, on average, been with the same employer for about six years. By the time boomers born ten years later reached their thirties, however, they had been with their current employer an average of just four years (see the first two dots on the purple line in the graph). By comparing two groups of workers as they hit the same career milestones, we can see an apples-to-apples comparison of how tenure changes over time.

As the graph shows, the downward trend continued with millennials. When baby boomers were in their 20s, the median boomer had four years of experience with their current employer. Today, the median millennial in his or her 20s has been in their current job for only a year, following a broader societal trend that spans across ages and generations.

It may seem counterintuitive that the median job tenure in all subgroups is declining while the aggregate median is slightly increasing. But that may simply be an artifact in differences in the size of each generation, sometimes referred to as Simpson’s paradox. Today, the baby boom generation is a large force in the labor market, and their size may be distorting the overall trends.

By looking at each generation over time, it’s clear the mobility trend is real, and it’s not a new phenomenon. It has implications in many areas, including how we think about job training, health care, and retirement benefits, not to mention broader societal effects. In order to propose solutions to those problems, however, we must first debunk existing myths and diagnose the problems accurately.