Nearly 100 years ago, states created teacher pension plans that were designed to serve a particular group of educators, especially women, who never married or had children. The publicly-funded systems were justified as protection for women who had taught for their full professional career, who likely didn’t have much in the way of personal retirement savings and would otherwise go without retirement support.

Pensions have evolved somewhat over time, but they’ve never escaped this original intent. Today, pensions provide financial security for those teachers that stay in the profession, but they also quietly push out veteran teachers. These leaders may have more to give to the classroom, but they are financially penalized for doing so. In a new paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, Maria Fitzpatrick suggests those incentive structures may be having an impact on women's retirement rates more broadly.

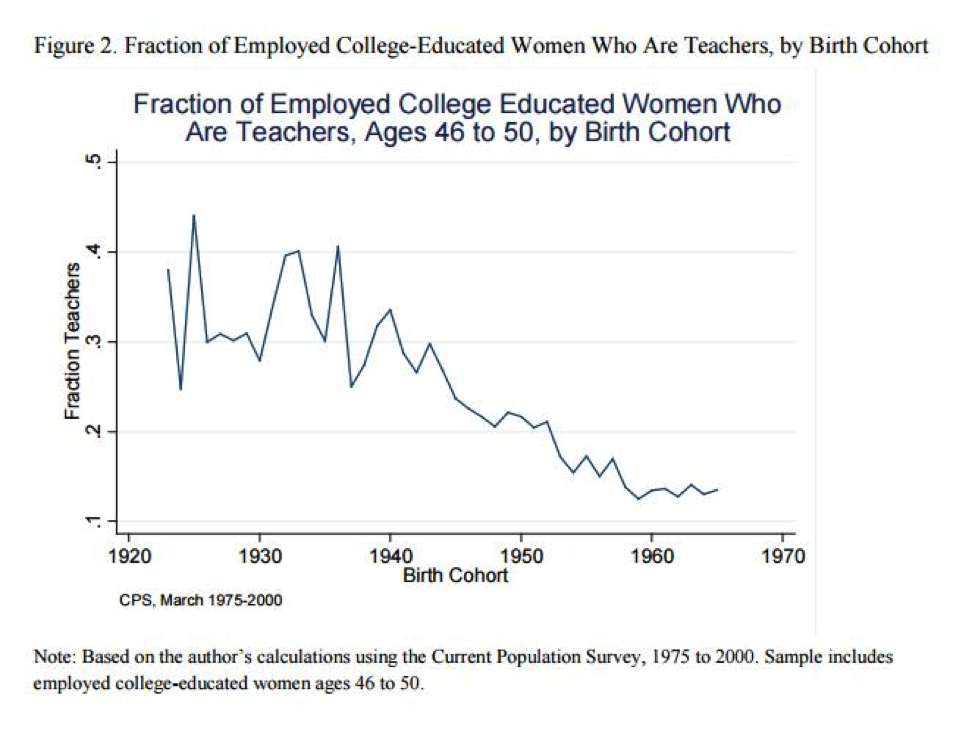

Fitzgerald found that between 2000 and 2010, labor force participation rates of college-educated women between the ages of 60 and 64 jumped 20 percent. At the same time, as shown in the figure below, a lower proportion of these college-educated women were ever teachers. Fitzgerald’s paper suggests this is because fewer college-educated women are becoming teachers.

This has several implications. One, it’s a tangible sign that college-educated women have more career options than they did in the past. Whereas 30-40 percent of college-educated women born in the first part of the 20th century became teachers, today that figure is closer to 15 percent. The expansion of opportunities for women is undoubtedly a good thing, no question, but it also meant a smaller potential labor pool for schools.

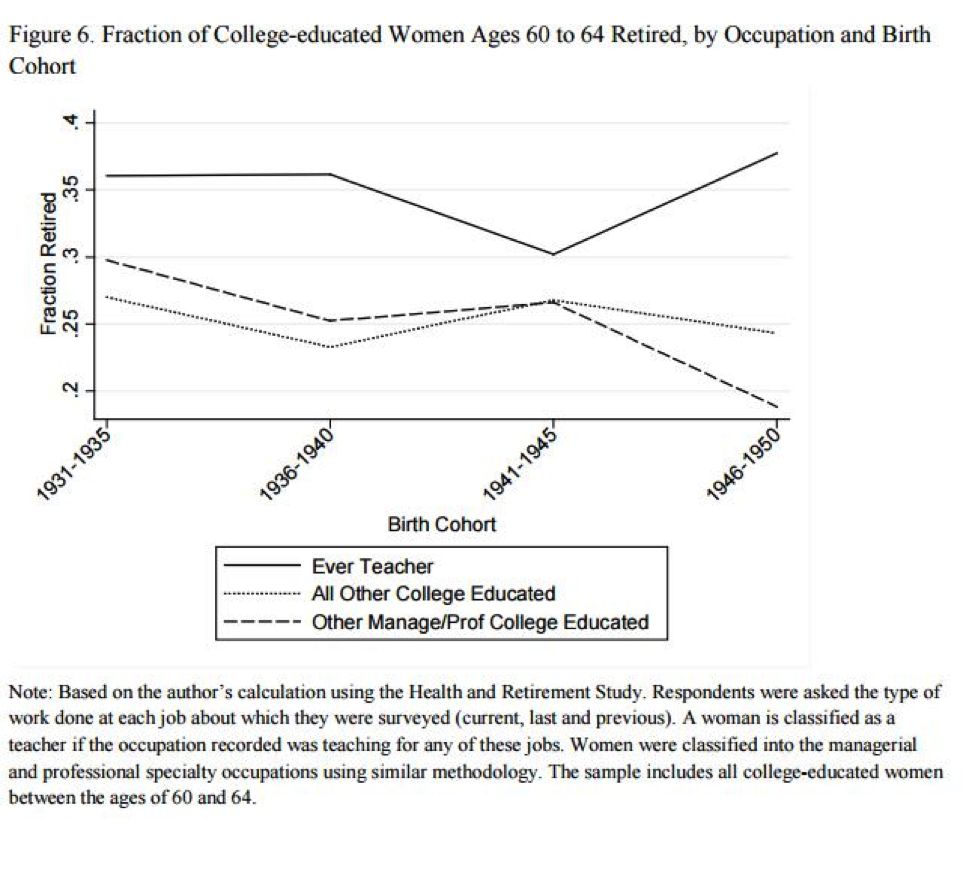

Two, because 90 percent of teachers are enrolled in defined benefit pension plans that push out veteran teachers, these demographic trends have widened the gap in retirement ages. Figure 6 from Fitzpatrick’s paper shows that female teachers are exiting the workforce sooner than their non-teaching peers. Fitzpatrick argues that this is linked to teachers’ participation in defined benefit pension plans, which encourage retirement at ages earlier than Social Security. That disconnect, where teachers have earlier retirement ages and longer retirement periods, has broader societal and cost implications.

So what does this mean? Recent National Center for Education Statistics data show that retirement security is a driving factor in teachers’ career decisions. So much so, in fact, that the ability to maintain teacher retirement benefits ranked above salary, class size, and child care availability in teachers who had left the classroom’s decisions to return. Effective, veteran teachers deserve fair retirement savings plans that continue to grow in value, rather than arbitrarily peaking and plummeting at a set age. Pensions aren’t keeping up with a changing society.