I recently read a story about the statewide teacher salary schedule in North Carolina. Politicians there are debating various changes for the upcoming year, but what caught my eye was the weird way North Carolina pays its teachers.

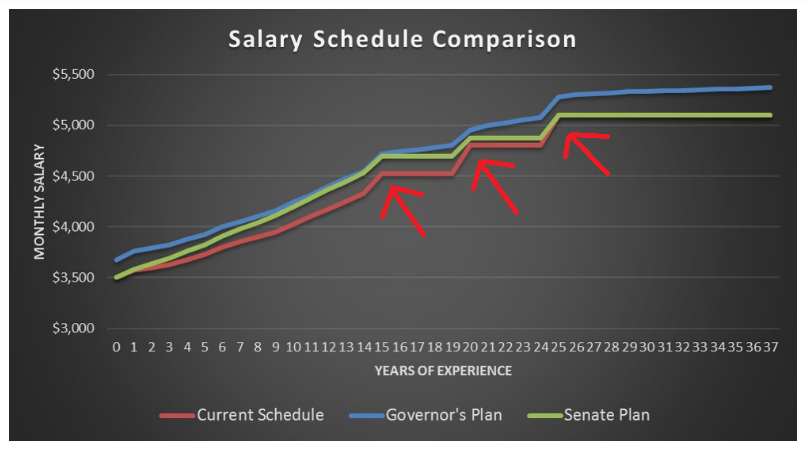

I pulled the graphic below, from a blog by The Progressive Pulse, to show what I mean. The graph shows the current salary schedule (in red) versus two competing proposals from the Governor and state Senate. My focus was on the red line. North Carolina teachers earn very small raises (of 0.5 to 2.5 percent) from years 1-14, and then they earn a 4.6 percent raise upon reaching 15 years of experience, then nothing until year 20, when they get a 6 percent bump, and then nothing again until year 25, when they get another a 6.25 percent bump. I added the arrows pointing to these weird kinks.

It's easy to imagine how North Carolina got to this place, but those back-end lumps are not tackling North Carolina's real turnover problems. Like every other state, the bulk of North Carolina's teacher turnover happens in the early years, and the vast majority of its incoming teachers will never reach these back-end bonuses (the state estimates only 28 percent will reach the 15-year mark). Worse, these back-end salary bumps are also not doing much to shape the retention decisions for those teachers who do reach them, at least not according to the state's pension plan.

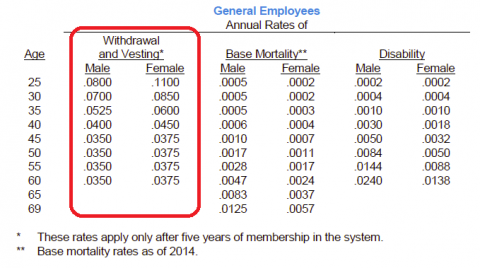

To show what I mean, I pulled the graphic below from the Actuarial Valuation report from the Teachers’ and State Employees’ Retirement System of North Carolina. I drew a red circle over North Carolina's official estimates for how many teachers will leave each year, based on their age. North Carolina has a separate set of assumptions for teachers in their first four years on the job, but it switches to these age-based estimates after that. (The chart can be read as, "For 25-year-old females, North Carolina assumes 11 percent will leave the state's public schools in that given year.)

Note that, while North Carolina's statewide salary schedule is based on years of experience, the state pension plan hinges the bulk of its assumptions on age, not years of experience. That is, after four years, the pension plan does not feel the need to account for the salary schedule's age-based longevity incentives. Even if there were a connection to years of experience, the state is not assuming any bumps in retention rates tied to any particular age.

To put it bluntly, North Carolina's pension plan does not assume that its statewide teacher salary schedule is affecting turnover rates.

This isn't unusual. The New York City teacher salary schedule has weird kinks at years 10, 13, 15, 18, 20, and 22. For example, after receiving no raise in year 21, a New York City teacher earns a $5,511 raise in year 22, a bump of 5.8 percent. But New York City's own pension plan doesn't assume this matters enough to affect its financial situation. Here are the corresponding withdrawal assumptions for the Teachers’ Retirement System of the City of New York:

This is a pretty straightforward chart. (It can be read, "New York City assumes 9 percent of teachers with 0-5 years of service will leave within the next year.") New York City is assuming that teacher turnover rates fall every five years. This is a much less incremental approach than the assumptions North Carolina uses, which makes it even more obvious that New York City's salary bumps at years 10, 13, 15, 18, 20, and 22 are not doing enough to shape teacher behavior to warrant adjusting the pension plan's assumptions.

Now, it's possible that teachers are responding to these lumpy incentives, and the pension assumptions simply aren't fine-grained enough to detect them. But that means something too. Those pension plan assumptions are the basis for consequential financial decisions about how much the state or city needs to save today in order to pay benefits in the future. While states and cities are spending a lot of money on back-end incentives like this, their own pension plans don't think it's worth altering their assumptions to account for them.