Since the vast majority of school districts employ uniform salary schedules, it seems reasonable to expect that educators should not experience gender-or race-based salary disparities’. Unfortunately, that is not the case. And to make matters worse, disparities in salary continue and grow through retirement.

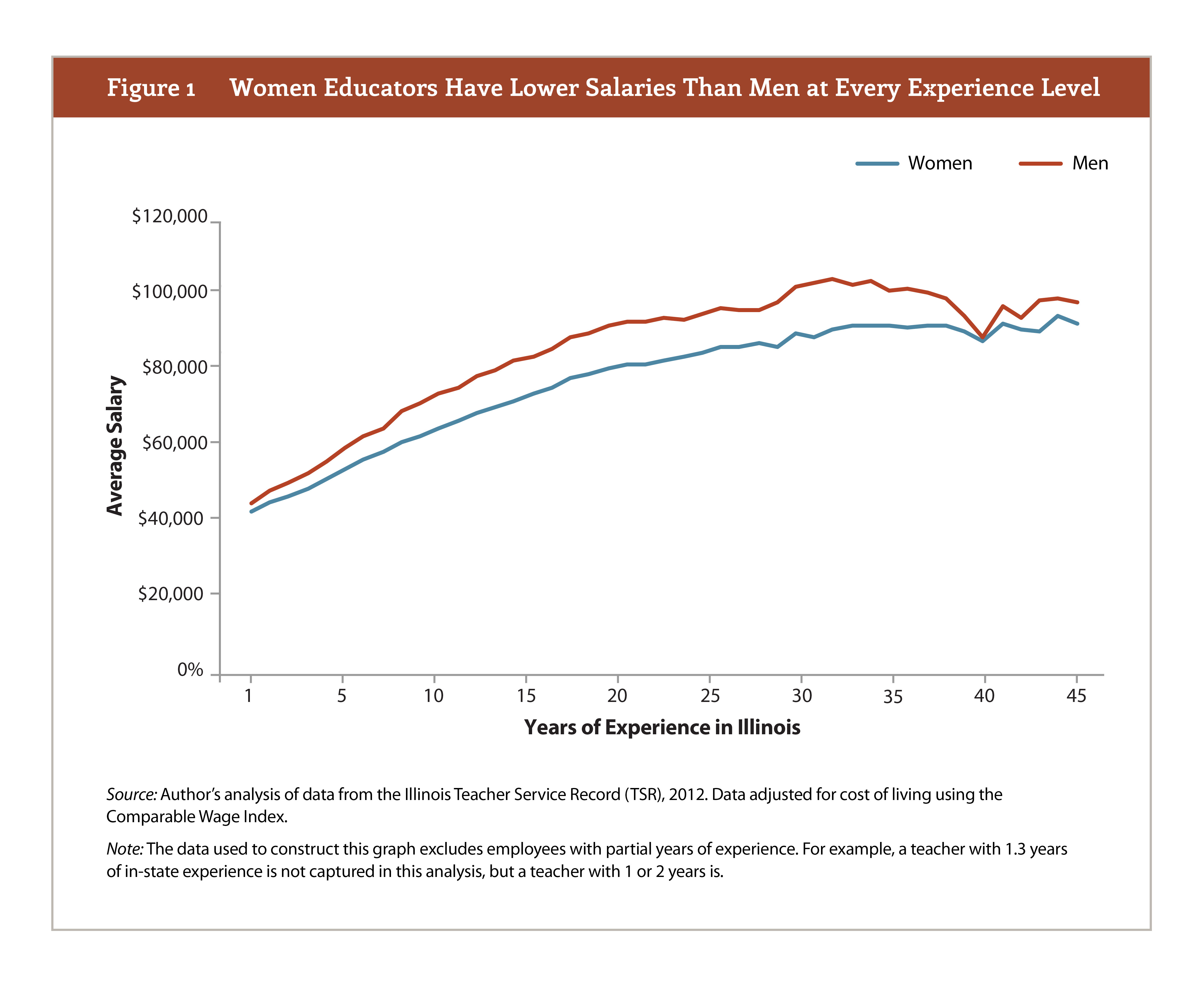

In a new report, we studied Illinois’ educator salary and tenure data, and found that women typically earn salaries that are $5,500 lower than their male colleagues. The salary gap exists as soon as women begin their careers. In year one, women earn on average $2,100 less than men. As shown in the graph below, the gender-based salary disparity persists and grows until educators reach their 30th year of service.

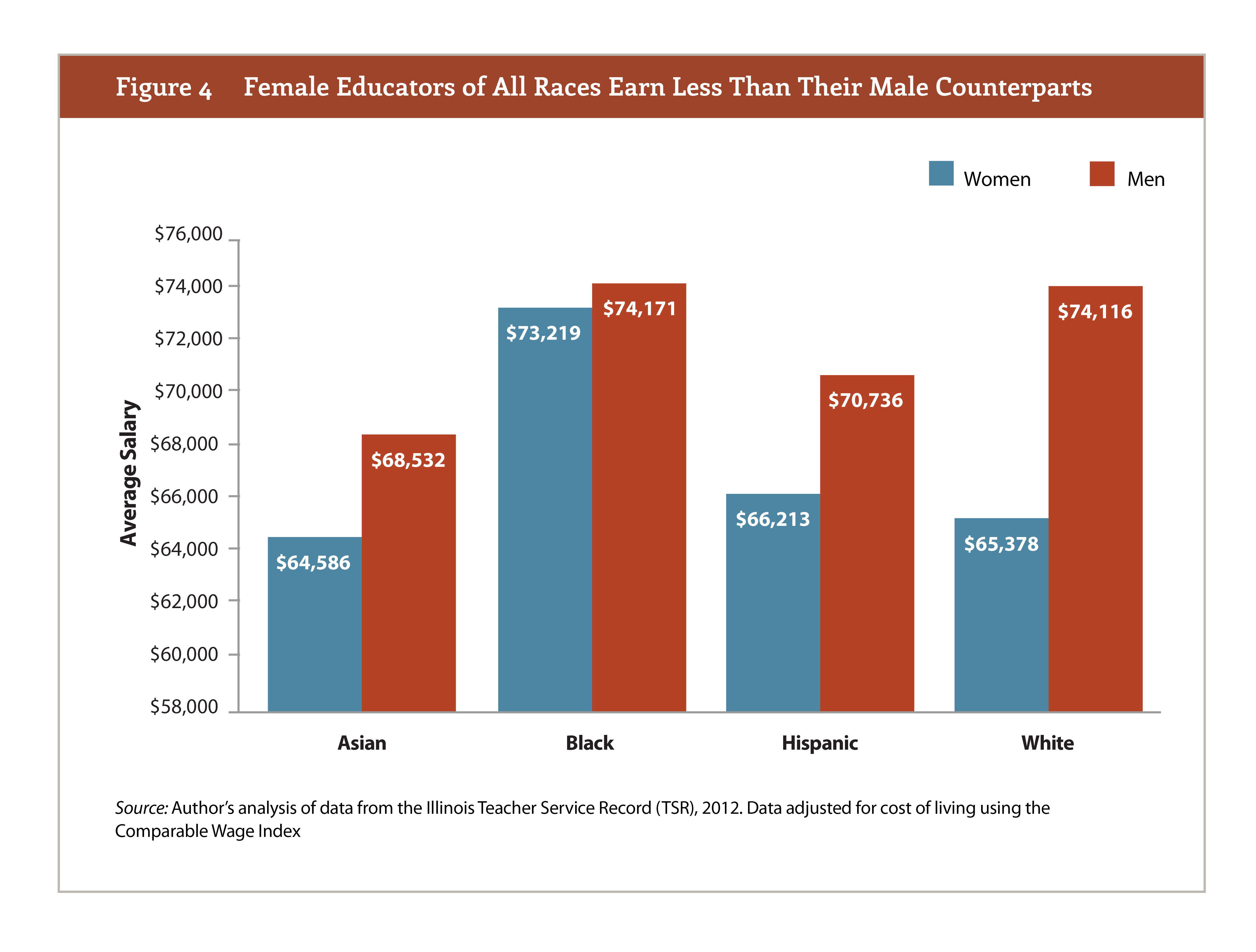

There are significant gender-based pay disparities within races and ethnicities. As shown below, women on average earn lower salaries than their male colleagues regardless of race. Hispanic men, for example, earn salaries around $4,500 more than Hispanic women. The largest gap is actually among white educators, while black educators have the closest average salaries. This is likely due to the fact that nonwhite educators primarily work in Illinois’ cities and suburbs, which pay the highest salaries in the state.

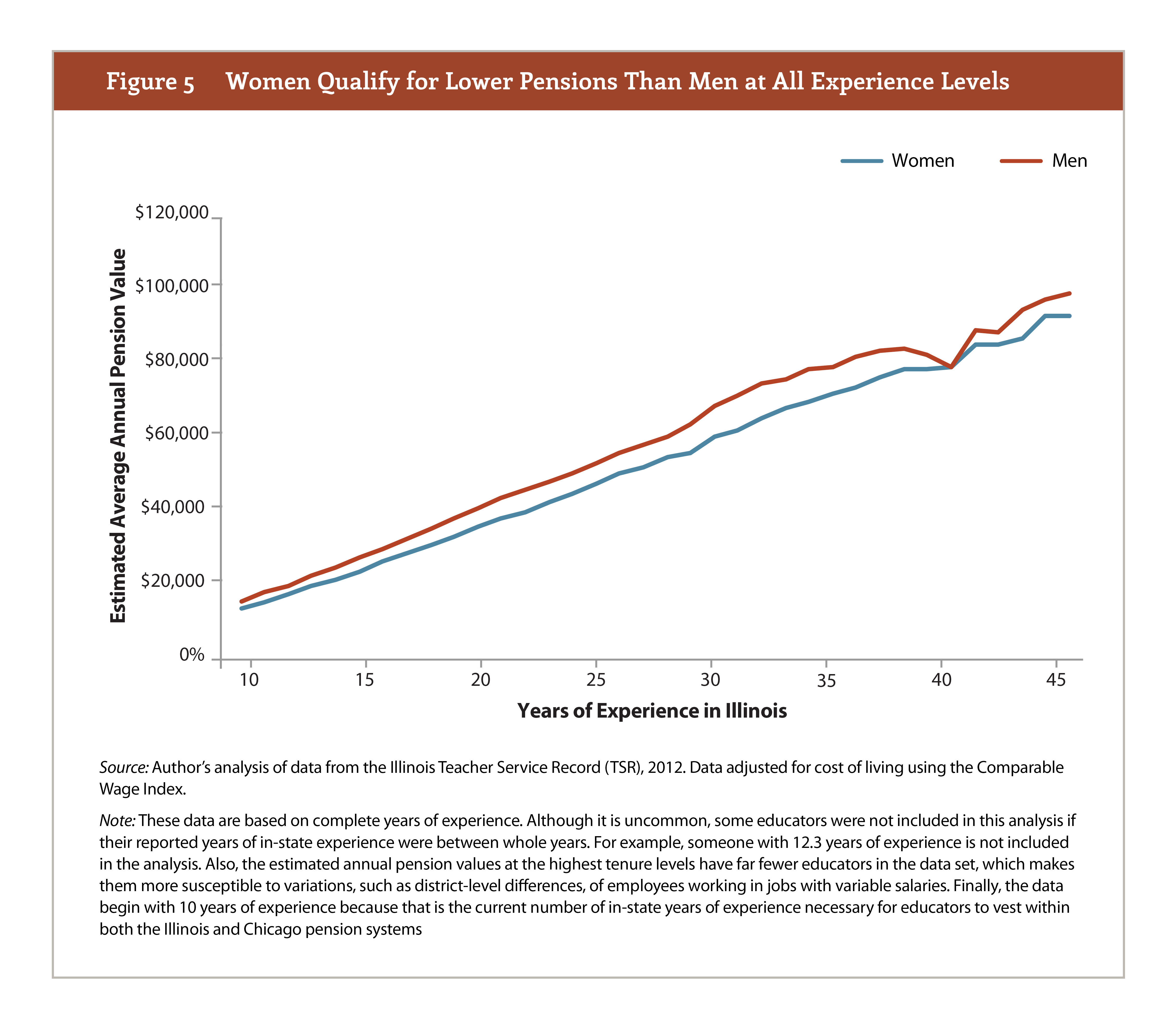

But unfortunately, salary gaps only tell part of the story. These inequities echo in retirement, resulting in even lower overall compensation for women compared with men. In fact, by excluding retirement wealth from analyses of gender-and race-based disparities in pay, we overlook the full extent of the problem. As shown in the graph below, women also earn less valuable pensions at every experience level.

After about 30 years of experience – a full working career – women’s estimated average annual pension value is $8,000 less than her male colleagues. After 10 years, men will have amassed $80,000 more in total retirement wealth than women who worked the same number of years. This pattern holds regardless for all races and ethnicities except for black educators. Black women early slightly larger annual pensions, which is likely due to the fact that they work longer and work exclusively in high-paying districts. Finally, while it is true that women tend to live longer than men, longer life does not eliminate the pension wealth gap, and it also requires women to live well into their 80s and 90s.

States and districts must recognize that large pay and retirement wealth gaps exist despite the use of uniform salary schedules. To address these problems, states and districts should consider:

- Analyzing their data to determine if they pay educators similar salaries for similar performance.

- Assessing whether an educator’s salary trajectory suffers unduly when they need to take time off, such as new or expecting mothers, to care for their family.

- Considering their rules on where incoming educators are placed on the salary schedule and whether provisions capping the number of years of credited experience disadvantages certain groups of workers.

- Evaluating promotion and leadership pipeline data and practices to identify race-or gender-based inequities.

To learn more about gender-and race-based educator salary and pension inequities, read the full paper here.