By now it's become something of a joke on social media, but earlier this month MarketWatch tweeted that, "By 35, you should have twice your salary saved, according to retirement experts." The original source for the tweet is a set of calculations by Fidelity Investments. It may be funny to joke about--my favorites involve acquiring a wide variety of Tupperware, plastic bags, and electric cords--but the Fidelity targets were an earnest attempt to estimate how much people should have saved at various ages in order to be on a path to a secure retirement.

The Fidelity targets are ambitious, but they're not crazy. They start with the assumption that people should aim to replace 45 percent of their income every year in retirement. That level of savings, plus Social Security, should afford someone to comfortably retire at age 67. Fidelity works backwards from there to estimate how much people should have saved at every stage of their career. The targets are framed as a percentage of income on the assumption that people should aim for a similar lifestyle in retirement as they enjoyed during their working years.

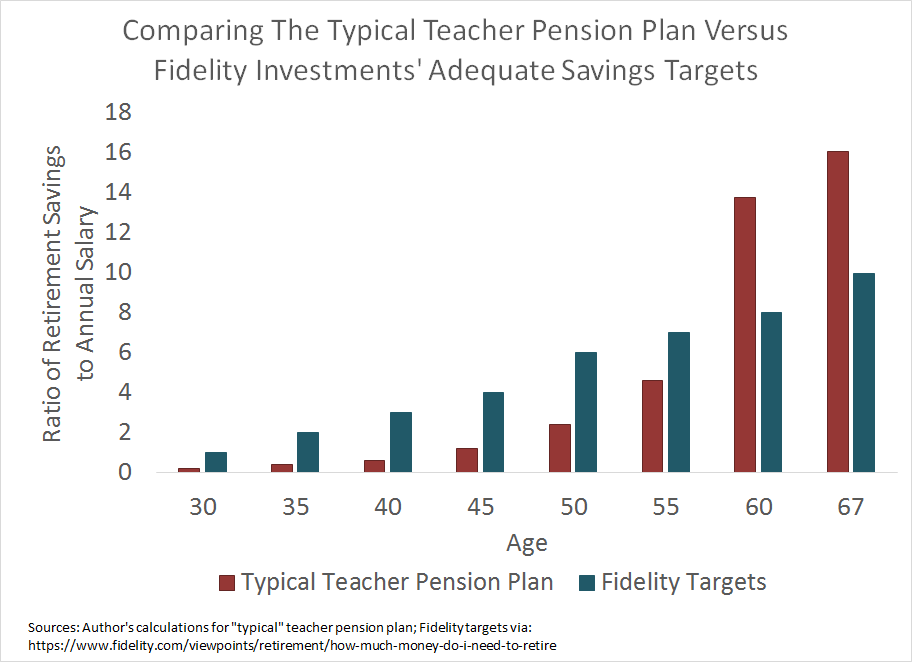

Given the perception of teacher pensions as being extremely generous, I set out to compare the typical teacher pension plan against the Fidelity targets. Using data from the National Council on Teacher Quality, I created a "typical" teacher retirement plan and then compared how assets accumulate for a typical public school teacher versus what Fidelity recommends.

As the graph below illustrates, the typical state-run pension plan forces teachers to suffer from years of low savings. If a teacher leaves the profession short of a full career, she may qualify for a pension, but it won't be large enough to provide for a comfortable retirement. To reach the same level of retirement security, ex-teachers will have to save more in later years, retire later, work longer, or depend on family members.

The graph also shows the opposite end. For the fraction of teachers who do stay for a full career, the typical pension system works fairly well. If they stick it out and continue teaching well into their 60s, their retirement income will start to beat out the Fidelity targets. (Due in part to the way the plans are structured and when they allow teachers to retire, most teachers, even full-career teachers, retire well before their mid-60s.) Still, this level of retirement security is only provided to those who remain as teachers in one state for their entire careers. Depending on the state, that's only 15-20 percent of incoming teachers. The rest fall short.

Public school teachers could have their own personal investments that might make help make up the difference, but the graph above may be under-selling the issue somewhat, since Fidelity's targets take Social Security for granted. About 40 percent of public school teachers do not have Social Security, so they're even more vulnerable to back-loaded teacher pension plans.

As the jokes made clear, many people find the Fidelity targets unrealistic. And they may be for lots of young people facing other financial pressures. But they're simply one way to gauge retirement readiness. And public school teachers aren't passing the test.