A Ponzi, or pyramid, scheme depends on constantly having new people come in at the bottom to prop up the top.

Theoretically speaking, teacher pension plans are not Ponzi schemes. Beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, states recognized that they needed to save for the pension promises they were making. If everything went according to plan, they wouldn’t have to rely on new members to fulfill those promises.

Unfortunately, many teacher pension plans have become Ponzi-like because of the way they’ve been managed. As I showed in the first installment of this series, teacher pension plans have amassed $800 billion in pension debts, thanks in large part to underestimating how much they needed to save and overestimating how fast their investments would grow.

In response, states have raised employee and employer contribution rates, effectively reducing the take-home pay for active teachers while also cutting into the discretionary budget districts have to pay them.

States have also cut benefits for new members. As extreme examples, newly hired teachers in Illinois and Ohio are now receiving a negative retirement benefit — on average, they will contribute more of their own money than they’ll ever get back in benefits.

Like Ponzi schemes, teacher pension plans also assume that new members will continue to be added to the system as it grows over time. But what if those assumptions are no longer correct? What if membership numbers start to flatline or even decline?

Student Enrollment Is Falling

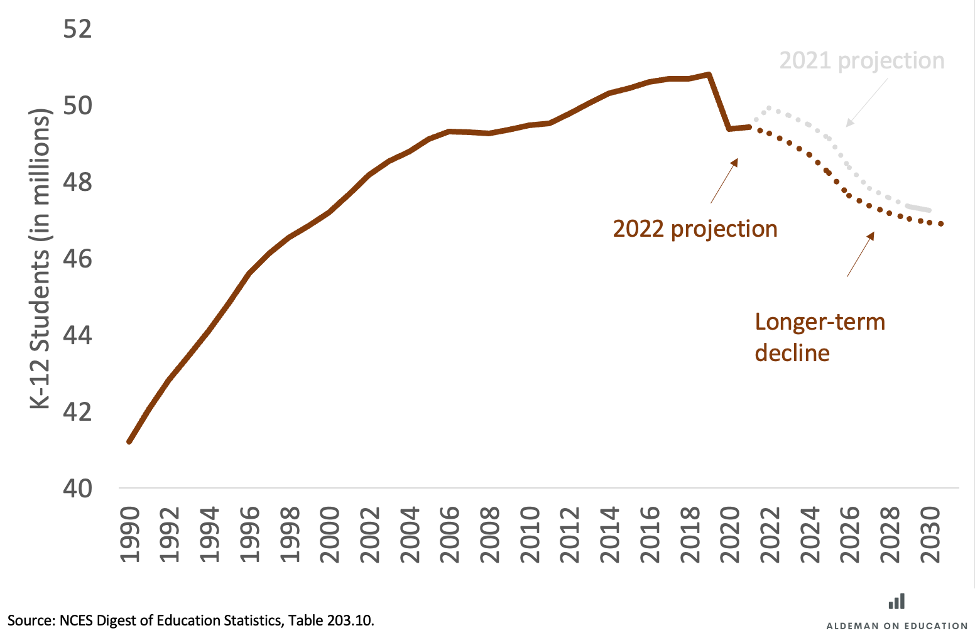

The school closures in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic led to an immediate decline of 1.4 million public school students (a 2.8% decline). This stemmed from a number of factors: a rise in homeschooling, a shift to private schools, kindergarten delays, and some students who were simply missing.

It may sound crass, but pension plans are concerned about their membership, not students. And thanks to the combination of rising state budgets and a one-time infusion of $190 billion in federal funds, district budgets have remained strong and the lower student enrollment has not translated into a meaningful decline in pension plan membership. The 10 largest teacher pension plans ended the 2021-22 school year with a combined 1,480 fewer members than they had at the same time in 2019, a decline of just 0.05%.

But the disconnect between student enrollment and pension system membership can’t last forever. State budgets are starting to plateau, and the federal money will run out in September of next year. Meanwhile, enrollment is projected to continue falling. Lower immigration and declining birth rates will cause student enrollment to fall through the rest of the decade. The National Center for Education Statistics now projects that public schools will lose an additional 2.4 million students (4.9%) between now and 2031.

Figure 1: After Decades of Growth, Public School Enrollment Is Now Falling

Enrollment changes will vary quite a bit from state to state. Thirteen states — including Florida, North Dakota, and Idaho — are actually projected to serve more students by the end of the decade.

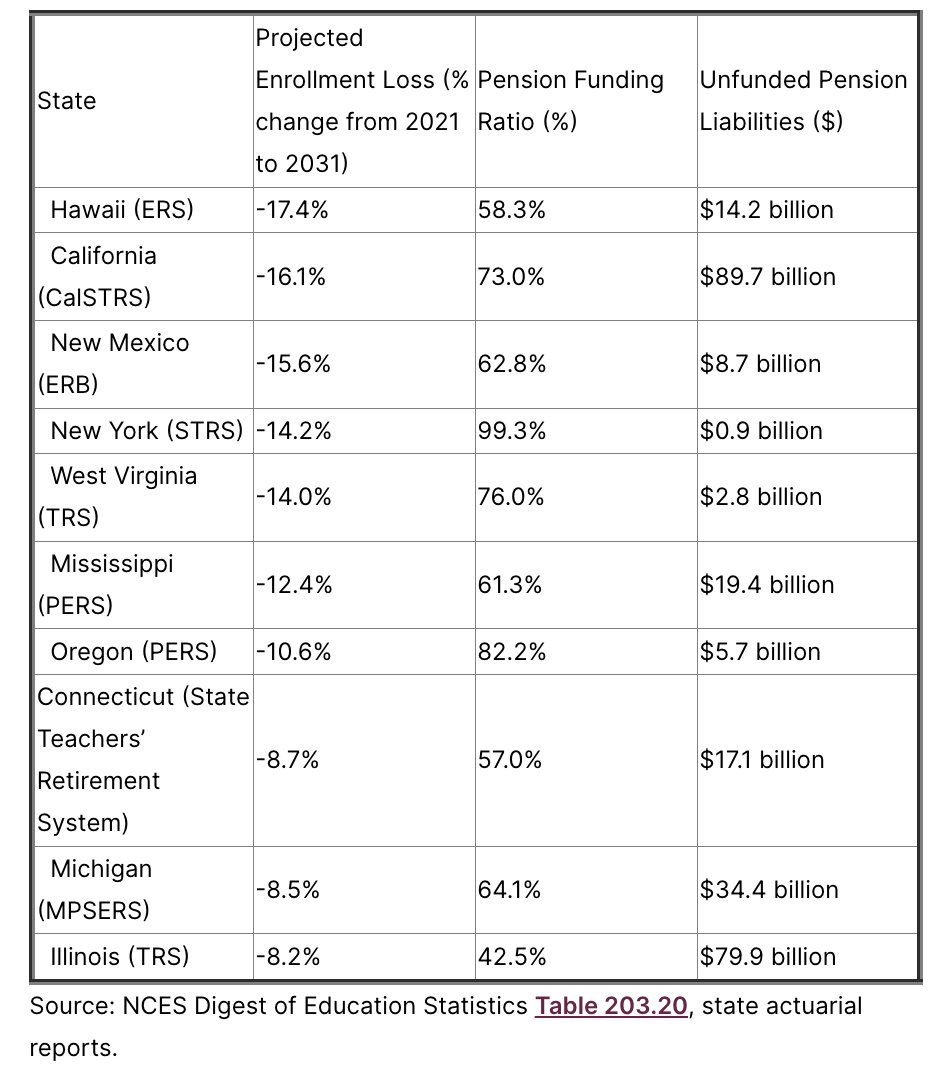

But in states facing steep enrollment declines, pension plans might be in real trouble. Table 1 below shows the 10 states with the largest projected student enrollment declines through 2031. Except for New York, which has managed to keep its pension debt costs in check, these states have dug themselves a large pension hole.

Table 1: States With the Largest Projected Enrollment Declines

It’s possible that pension plan membership will continue to grow even as student enrollment falls. But that would largely depend on state taxpayers being willing to support continued reductions in student-teacher staffing ratios.

If schools instead adjust their staffing levels to reflect student enrollment declines — well, then, watch out. Pension plans will have to pay off their existing pension debts on the backs of a shrinking pool of active workers.

Pyramid Schemes (Eventually) Collapse

At some point, Ponzi schemes collapse because there aren’t enough new entrants.

Teacher pension plans won’t collapse because their promises are backed by state taxpayers. But over time they’ve become a bigger and bigger financial strain on state and local education budgets. That trend shows no sign of slowing down. More funding going toward pension debt means less going to teacher salaries, classroom resources, building maintenance, and many other investments teachers and families care about.

So what can state legislators do? The specific details will vary by state, but I’d recommend four principles to help state leaders responsibly pay down their pension debts while mitigating the effects of enrollment declines:

1. Keep promises to current workers and retirees

Workers and retirees are not to blame for today’s pension problems. They didn’t create the pension formulas, set the contribution rates, or skip any payments — state leaders did. Pensions are a promise, and states should keep them. Besides, in many states, it would be illegal to change benefit rules for existing workers or retirees. State leaders need to look elsewhere for solutions.

2. Don’t pass the problem on to districts

School district leaders didn’t create these pension problems, either, and they shouldn’t have to pay for debt they didn’t incur. Plus, states have a larger and more equitable tax base than local communities do. As such, the state should bear the full responsibility for paying off pension debts.

3. Actually pay down pension debts

This one might seem obvious, but many states are using financial wizardry to hide the true cost of their pension plans. Some make overly aggressive investment assumptions to justify contributing less than they should. Others roll over their pension debts year after year in a process akin to paying the minimum payment on a credit card while letting the total balance grow over time.

These types of shenanigans can lead to “negative amortization,” in which pension plans slowly build up debt without making any progress on the principle. That helps keep costs (artificially) low in the short run but will cause even worse problems if (when?) membership starts to decline.

States should instead adopt more honest funding practices to ensure they can meet their obligations to workers and retirees. Once they commit to a funding plan, they should seek out a dedicated source of revenue — such as bonds, a special tax on millionaires, or “sin” taxes on marijuana or gambling — to pay down their debts over time.

4. Guarantee a path to a secure retirement for all workers

Traditional pension plans are “guaranteed” in the sense that the promises are backed by taxpayers. But workers are not guaranteed to benefit. Because of the way the formulas work, the majority of new teachers don’t stay long enough to qualify for any benefits, let alone good ones.

Instead, states should consider cash balance plans, hybrid plans, or even well-structured defined contribution plans that put all workers on a path to a secure retirement, no matter how long they remain as teachers.

These types of alternative plan designs are better for workers. Taxpayers would benefit, too. We all benefit when more workers have access to high-quality retirement plans rather than being dependent on social insurance programs. These plans also reduce or eliminate the chance of adding to the state’s pension debts going forward. Rather than using education budgets to pay for the mistakes of the past — as they are increasingly doing today — all of the money set aside for education could go to current workers, programs, and services.

If policymakers follow these steps and respond to rising pension costs, they can help teachers and ensure that more money intended for schools makes it into classrooms.