Social Security, Teacher Pensions, and the “Qualified” Retirement Plan Test

Most Americans depend on Social Security benefits to lead a comfortable and secure retirement. Among all Americans over age 65, Social Security makes up more than half of their household income.[1]

And yet not all workers can count on Social Security. Due to a historical quirk, many local and state government employees lack the retirement and social safety net offered by Social Security. Public school teachers constitute one of the largest groups of uncovered workers.[2] Nationwide, approximately 1.2 million active teachers (about 40 percent of all public K-12 teachers) are not covered.[3] Those teachers are concentrated in 15 states — Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Texas — and the District of Columbia, where many or all public school teachers neither pay into nor receive benefits from the system.

In 1990, Congress attempted to ensure that all public-sector workers were either covered by Social Security or enrolled in a retirement system provided by their state or local government.[4] To enforce this provision, Congress directed the Secretary of the Treasury to define the term “retirement system” through regulation.

In its subsequent regulations, the IRS determined that state and local government retirement plans provide sufficient benefits if they are at least as generous as Social Security itself. The IRS also created simple “safe harbor” formulas to test whether those plans were providing sufficient retirement benefits to their workers. These thresholds are intended to apply to each individual worker, and if a retirement plan’s benefits fall below what Social Security would provide for even a single day of any worker’s career, the state or local government must either raise benefits or enroll in Social Security all workers who fall below the threshold.

In theory, the safe harbor formulas provide an easy-to-understand test for state and local government retirement plans while also setting a base floor of retirement benefits conveyed to workers covered by those plans. In recent years, states have struggled to fund their pension plans and in response have cut benefits for new workers.[5] During those rounds of cuts, the safe harbor formulas have provided a clear and straightforward bar below which state and local policymakers cannot cut benefits.

However, while the safe harbor rules are simple and clear, they are failing to deliver on their intended purpose. The safe harbor provision governing defined benefit pension plans, like the ones enrolling 90 percent of teachers, relies on formulas that leave many short- and medium-term teachers with retirement benefits worth significantly less than what they could have earned under Social Security.[6] While the current safe harbor rule is easy for policymakers to follow, it ignores many other variables that materially affect the retirement benefits workers actually receive. Worse, the safe harbor rule works better for the highest-paid, longest-serving workers while leaving the most vulnerable workers short.

This situation is not trivial. In addition to millions of active workers who aren’t covered by Social Security, there are currently about 20 million retirees who performed some government service as non-covered employees.[7] Many of those workers are now facing a lower standard of living in retirement due to the flaws in these seemingly arcane rules.

To fix this problem once and for all, Congress must act. All workers deserve the retirement and disability protections afforded by Social Security. After all, states on their own will never match the national portability provided by Social Security, and they have chosen not to match the progressive, inflation-adjusted benefits Social Security offers. States could unilaterally choose to join Social Security, but universal coverage would make the system far simpler and more sustainable for all participants.

Short of passing legislation, Congress should use its oversight powers to hold public hearings and investigate how the safe harbor rules are affecting constituents. The Department of the Treasury should also revisit its regulations to more accurately align the benefits provided under safe harbor to how benefits accumulate under Social Security itself.

This brief outlines the history of Social Security benefits in the public sector, describes the safe harbor rule and how it is intended to work, and then shows its limitations. As a concrete example, it then analyzes the pension formulas covering approximately 1.2 million active public school teachers in the 15 states and the District of Columbia that do not offer universal coverage for teachers. Similar to previous work, it shows that the pension formulas in those states do not protect teachers from receiving retirement benefits that are worth less than they would otherwise receive under Social Security.[8] Those workers should be covered by Social Security immediately. The brief concludes with suggestions about how IRS could amend its rules to protect these workers and more closely align its policies with congressional intent.

(Download a pdf of the report here.)

Social Security Coverage in the Public Sector

In 1935, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act, creating the precursor to the modern program we know today. At the time, it applied only to private-sector workers and excluded employees of federal, state, and local governments.[9] Beginning in 1954, Congress extended the law to allow state and local governments to voluntarily provide Social Security coverage to their employees.3 Most public school teachers at the time were already enrolled in state-run defined benefit (DB) pension plans, and a small but important subset of states chose not to join Social Security when given the chance on the theory that their existing pension plans could offer better benefits than Social Security could. To make up for the lack of Social Security, nonparticipating states today tend to offer slightly more generous pension formulas than states that combine both Social Security and their own statewide retirement plan.[10]

That mix persisted until the 1980s, when Congress extended coverage to newly hired federal workers. And, in 1990, Congress required state and local governments to enroll their workers in Social Security if they did not offer those workers a retirement plan. At the same time, Congress tasked the IRS with defining what qualified as a sufficient “retirement plan.” In the wake of the 1990 law, the IRS issued regulations that a public-sector worker is considered to be enrolled in a qualified retirement system if “he or she participates in a system that provides retirement benefits, and has an accrued benefit or receives an allocation under the system that is comparable to the benefits he or she would have or receive under Social Security.”[11]

For DB pension plans, like those offered to 90 percent of public school teachers, the IRS regulations state:

A defined benefit retirement system maintained by a State, political subdivision or instrumentality thereof meets the requirements of this paragraph (e)(2) with respect to an employee on a given day if and only if, on that day, the employee has an accrued benefit under the system that entitles the employee to an annual benefit commencing on or before his or her Social Security retirement age that is at least equal to the annual [retirement benefit] the employee would have under Social Security.[12]

The test is intended to assess whether plans deliver benefits that provide sufficient retirement savings for each individual on every single day he or she is employed. A plan could be considered a qualifying retirement plan for some workers, at some point in their career, but not for other workers or at all points in any individual worker’s career.[13]

Since 1991, the IRS has implemented the safe harbor provision for DB pension plans through a simple test: A DB plan qualifies if it pays out a monthly pension that is worth at least 1.5 percent of the employee’s salary, averaged over the last three years of service, multiplied by his or her years of service, beginning no later than the worker’s Social Security retirement age.[14] If an employee is enrolled in a pension plan meeting these requirements, they are considered to be enrolled in a qualified plan and are not required to join Social Security.

Today, there is still an uneven distribution of Social Security coverage across and even within the states. In fact, 5 million state and local government workers, including 1.2 million public school teachers, lack the protection of Social Security.[15] Among those currently without coverage are approximately 40 percent of public school teachers in states or districts that have chosen not to participate. Those teachers are concentrated in the District of Columbia and 15 states — Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Texas — where many or all public school teachers lack coverage.

Social Security coverage also can vary within states. For example, in California, all state government employees, state legislators, and judges are covered by Social Security, while teachers are covered solely by their state-provided pension plan. In Washington, D.C., teachers employed by the District of Columbia Public Schools are not covered by Social Security, but about half of the district’s teachers work in public charter schools, which generally do participate. A similar split exists across a few states, namely Georgia, Rhode Island, and Texas, which have left the coverage decision to local school districts, so even within a state’s education system there may be split coverage. As discussed below, teachers in these states with split coverage may be especially vulnerable to cracks in the IRS’ safe harbor rule.

The Safe Harbor Formula in Practice

The safe harbor formula is easy to implement — policymakers need to look at only a few basic details about the plan — but it ignores several variables that can substantially affect the benefit a worker ultimately receives.

First, the safe harbor rule specifically carves out an exception for states to employ “vesting periods” that impose minimum requirements on the number of years an employee must work before becoming eligible for pension benefits.[16] With no constraints on those vesting requirements, non-Social Security states can and do set long vesting periods. For teachers, eleven of the states without universal Social Security coverage require a five-year vesting period, while four states — Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, and Massachusetts — do not offer Social Security and withhold all employer-provided retirement benefits from teachers until they have reached 10 years of service.[17] These long vesting periods would be illegal in the private sector, where a federal law known as ERISA requires all employees to vest within no more than seven years. Across the states that do not offer Social Security coverage to their teachers, a previous study found that an average of 52 percent of new teachers will fail to vest into their state retirement system, leaving them with no retirement benefit at all.[18] The IRS rules allow for this result by specifically exempting vesting periods from the safe harbor test.[19]

Second, the safe harbor provision does not consider employee contribution rates. From the IRS’ perspective, it doesn’t matter whether employees or employers are making contributions into the plan, but that question matters a great deal to workers and retirees. Illinois provides an extreme but real example of the problem with this omission. Illinois teachers are not covered by Social Security, but teachers hired after 2011 are required to contribute 9.4 percent of their salary toward the state pension plan, even as the pension plan itself estimates those benefits are worth only 7 percent of each teacher’s salary.[20] According to the IRS rules, the Illinois plan counts as a qualified retirement plan, even though the average Illinois teacher hired today is not receiving a positive retirement benefit at all — he or she is paying a tax. Illinois’ situation is an outlier, but the safe harbor provision does not look deep enough to protect against situations like this.

Third, the safe harbor rule is silent on the rules governing workers who leave the plan. Merely enrolling in a qualified plan is sufficient; the IRS rules ignore whether departing employees ever actually collect a benefit that matches those that were promised. This is not a small oversight. While not all states report the percentage of teachers who withdraw from the plan, California does report this data, and they find a not-insignificant share of teachers will eventually withdraw. In its official financial projections, the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) estimates, for example, that one-quarter to one-half of all 35-year-olds who leave the plan will eventually withdraw their contributions rather than wait to collect a pension.[21] In California, those withdrawing teachers are entitled to their own contributions, with a small amount of interest, but they do not qualify for any employer contribution, even if they are vested. However, in determining whether a state’s plan qualifies or not, the IRS does not look at the plan’s employee contribution rates, its rules around interest credits, or whether it offers any employer matching. Without looking at these elements, the IRS cannot guarantee that a state is providing minimal retirement savings to every worker on every day that employee works.[22]

But perhaps the biggest problem with the IRS rule governing DB pension plans is the way it measures benefits for workers. The IRS focuses only on the benefit formula itself, even as a large and growing body of literature has demonstrated that DB pension formulas deliver wealth in a back-loaded fashion.[23] Many teachers will leave their service before qualifying for those larger, late-career benefits. This delayed delivery of benefits violates the “on a given day” language in the IRS regulations, which were designed to ensure that all workers accrue retirement benefits every day and every year they work.

As the next section shows, this oversight has large consequences that undermine the intent of the rule. Without looking at how workers accumulate benefits across their entire careers, the rule fails to protect teachers who do not stay in a single state pension plan for their entire career.

How the Safe Harbor Provision Leaves Workers Short

Recall that IRS regulations require all full-time employees to be enrolled in Social Security unless “the employee has an accrued benefit ... that is at least equal to the annual [retirement benefit] the employee would have under Social Security.”14 This section attempts to measure whether the IRS safe harbor rule governing DB pension plans is living up to its own standard.

First, we have to measure the value of Social Security. Social Security benefits are based on the average of a worker’s highest 420 months (35 years) of earnings, adjusted for the growth in average wages. This is called the Average Indexed Monthly Earnings (AIME). The Social Security formula then applies “bend points” to convert the AIME into the worker’s monthly benefit (called the Primary Insurance Amount, or PIA). Those bend points are updated annually. In 2019, the formula replaces 90 percent of the AIME up to $926; 32 percent of the AIME between $926 and $5,583; and 15 percent of the AIME over $5,583. These bend points are what make Social Security progressive, because they replace a larger share of income for lower-paid workers than for higher earners.

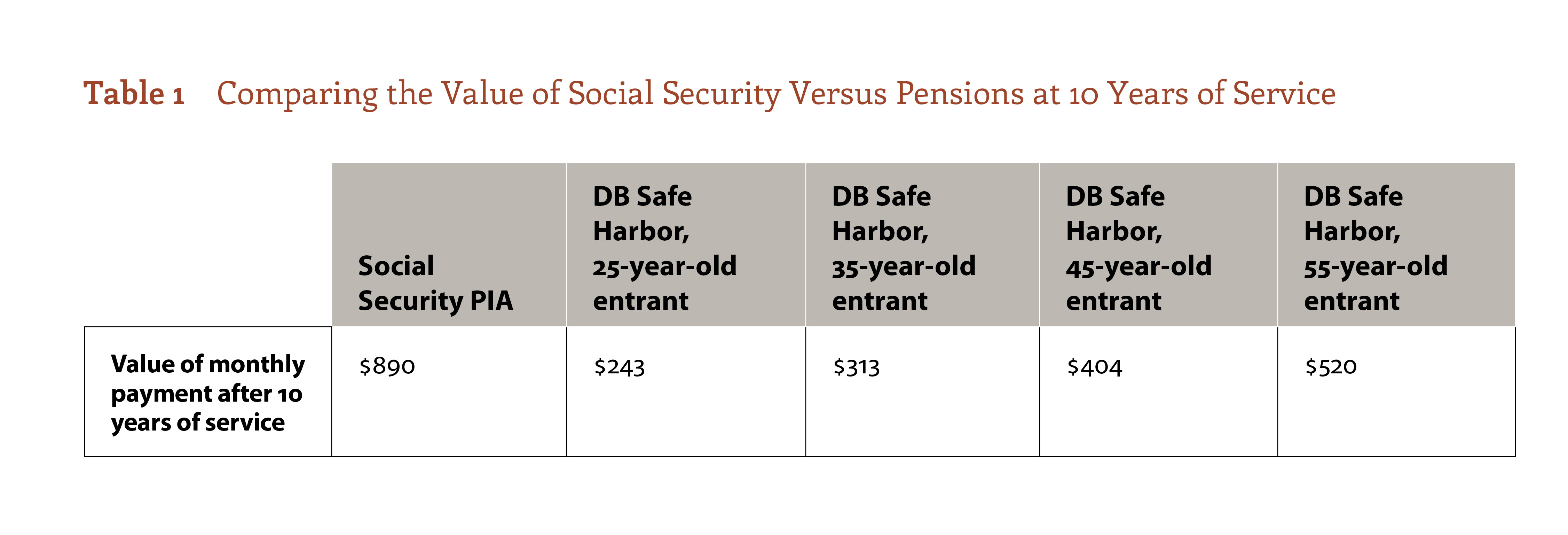

As an example, consider a worker who starts her employment earning $40,000 a year.[24] After 10 years of working, she’ll have enough credits to qualify for Social Security benefits when she retires. Assuming she earns real salary increases of 1 percent a year, after 10 years she’ll qualify for a Social Security benefit of $890 a month in today’s dollars. It doesn’t matter how old she is when she completes her years of service, because Social Security automatically adjusts her salary to inflation.[25]

Now consider the same worker’s benefit under the safe harbor rule governing DB pension plans. In this scenario, she earns the same salary as before and works the same 10 years. However, now instead of Social Security, she is enrolled in a pension plan with a formula that meets the IRS minimum. It will be based on her average salary over her final three years of working, multiplied by 1.5 percent times her total years of service. In contrast to Social Security, the salary used in her pension formula will not be adjusted for inflation, so it does matter when she completes her 10 years of service.

Table 1 below compares the results, broken out by when this hypothetical worker completes her 10 years of service. In real terms, someone who completed 10 years of service from ages 25 to 35 would qualify for a pension upon retirement worth only $243 per month in today’s dollars. In comparison, if the worker completed her years of service between the ages of 55 to 65, she would be eligible for a pension worth $520 per month in today’s dollars. The IRS rules do not protect against this disparity. Worse still, all the 10-year pension values fall short of the value of Social Security.

Figure 1 below applies the same methodology above to show how benefits accumulate across the employee’s entire career, beginning at age 25. The blue line represents the value of the DB pension wealth guaranteed by the minimum IRS safe harbor rule, and the red line represents the value of the Social Security PIA. All the salary assumptions are the same as above.

With no prior earnings history, the Social Security PIA would be more valuable than the IRS safe harbor rule as soon as the worker reached the minimum Social Security credits after 10 years of employment.[26] Social Security would continue to offer a greater benefit until she turns 58, after her 33rd consecutive year of service.[27] If she leaves her uncovered employment at any point before then, she will qualify for a pension worth less than what she could have earned under Social Security.

In contrast to Social Security, which is designed to provide proportionately more generous benefits to lower-income and transient workers, the IRS safe harbor rules do the opposite; they offer better protections for higher-income, stable workers than they do for lower-income, transient workers.

Teachers Without Social Security Coverage

So far, we’ve focused only on how the IRS safe harbor provision works in theory. This section looks at how it plays out in practice for one particular group of workers — public school teachers in the 15 states without universal Social Security coverage.

As Table 2 illustrates, all the states that do not universally enroll their teachers in Social Security offer pension formulas that pass the bare minimum of the IRS safe harbor threshold. The safe harbor threshold represents a floor under which these states cannot cut benefits (or else enroll workers in Social Security), but most of these states are offering benefits that are well above the IRS thresholds in terms of their formula multipliers and normal retirement ages.

With these more generous benefits, are teachers earning retirement benefits that are at least as generous as the Social Security PIA? For the same structural reasons outlined above, the answer is no.

To illustrate what this looks like under particular state pension plans, consider the case of a new teacher hired at age 25 in California. She will be automatically enrolled in the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS). As a newly hired CalSTRS member, she will be eligible for a pension equal to 2 percent times her years of service times the average of her highest three years of salary. She can begin collecting that pension beginning at age 62.[28] CalSTRS members do not participate in Social Security, so she will be solely dependent on her state-provided pension plus any personal savings.

Figure 2 below compares the value of the worker’s CalSTRS benefit versus what she would have earned under Social Security. As in the generic hypothetical described above, the CalSTRS system provides a much more generous benefit to longer-term veterans, but short- and medium-term teachers are at risk of leaving with less. In fact, a new, 25-year-old teacher would have to teach for 24 consecutive years in California before qualifying for a pension benefit that equaled or exceeded the value of the Social Security PIA.[29] Despite the fact that the plan parameters comply with the letter of the IRS regulations, the CalSTRS system provides benefits to many of its members that fall well short of the value of Social Security.

California is no exception. Table 3 replicates the above analysis for new, 25-year-old teachers in all states where Social Security coverage is not universal for teachers.[30] It uses the same salary assumptions as above but swaps in the applicable multipliers and normal retirement ages from each state plan. As the table shows, the lowest break-even point is 16 years in Missouri, which offers a multiplier of 2.5 percent and allows our hypothetical teacher to begin collecting full pension benefits at age 53. In contrast, the break-even point is 25 years in Illinois and Maine and would require teachers to stay 29 years in Rhode Island.[31]

There are some caveats to these findings. If we repeat the same analysis with higher salaries and faster wage growth, the “break-even” points become shorter.[32] Due to the way DB pension benefits suffer from inflation, the break-even points are also shorter for workers who enter their uncovered service at older ages (although those workers are more likely to enter their uncovered service already qualified for Social Security). The break-even calculations presented here also do not represent the total value of a worker’s lifetime benefits under either scenario. They estimate the value of a worker’s monthly benefit at age 67 but do not factor in how many years the teacher would be eligible to collect those benefits in retirement.[33] In all these states, long-serving veteran teachers would have pension benefits worth far more than the lifetime value of Social Security.

Still, a similar analysis came to similar conclusions even when looking at the total net present value of benefits, as opposed to monthly payments.[34] Moreover, comparing monthly payments is how the IRS defines a “qualified retirement plan,” and there are likely some teachers working in all these states today who qualify for benefits worth less than Social Security. According to the IRS rules, those teachers should be offered more generous benefits or be enrolled in Social Security immediately.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The odds are stacked against teachers and other public-sector workers who lack Social Security coverage. Congress directed the IRS to write a rule that would protect these workers, but the provision is not functioning as intended. Millions of current state and local government workers are affected. They are at risk of leaving their public service with retirement benefits worth less than what they would have received under Social Security. The safe harbor formula covering DB plans, as currently enforced, ensures adequate protections only to long-serving veteran workers, while leaving short- and medium-term workers, especially lower-paid ones, without adequate retirement benefits.

There are three potential paths forward. At the national level, Congress could decide that all public workers deserve the retirement and disability protections afforded by Social Security. States on their own can never match the national portability provided by Social Security, and they have chosen not to match the progressive, inflation-adjusted benefits Social Security offers. Moreover, the WEP and GPO provisions introduce unnecessary complications into the program and have led to hundreds of millions of dollars in overpayments each year. Universal coverage would solve all these problems.

Short of passing legislation, congressional leaders should use their oversight powers to hold public hearings on the safe harbor rules. Members of Congress could also ask the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) to study this issue and recommend potential solutions. In response, the IRS should revisit the safe harbor rules and ensure that its definition of “qualified” retirement plans aligns with congressional intent. With such a revision, the IRS should focus on the accumulation of retirement savings and look beyond basic pension formula variables. Without looking deeper than surface-level elements, the IRS will not be able to accurately determine whether workers are truly accumulating sufficient retirement assets.

Even in the absence of federal action, states that don’t offer Social Security coverage should reevaluate how they provide retirement benefits to workers. Too many teachers today serve under retirement plans that provide sufficient benefits only to those who stay in one system for very long periods of time. That arrangement works for a small minority of workers who remain in a single system for their entire career and qualify for a sizable pension, but not at all for the majority of teachers. Teachers who don’t vest into their state’s pension system or who qualify for only a modest pension are losing out. Social Security coverage would provide a solid foundation for all workers and guarantee a steady accumulation of retirement wealth, regardless of any teacher’s long-term career path. Integrating Social Security into a state retirement system would help provide all teachers with secure retirement benefits.

(Download a pdf of the report here.)

[1] Table 8.A1: “Section 8: Importance of Income Sources Relative to Total Income,” Income of the Population 55 or Older, Social Security Administration, 2014, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/income_pop55/2014/sect08.pdf.

[2] Internal Revenue Service, Social Security Administration, and National Conference of State Social Security Administrators, “Federal-State Reference Guide,” Federal-State Cooperative Publication, November 2013.

[3] Of the more than 3 million public school teachers, approximately 40 percent are not covered by Social Security. National Center for Education Statistics, “Fast Facts,” Institute of Education Sciences, 2012. National Education Association, “Characteristics of Large Public Education Pension Plans,” 2010. Chad Aldeman and Andrew J. Rotherham, “Friends without Benefits,” Bellwether Education Partners, 2014, http://www.teacherpensions.org/resource/friends-without-benefits.

[4] Rep. Leon Panetta, “H.R.5835 — Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990,” Congress.gov, https://www.congress.gov/bill/101st-congress/house-bill/5835/text.

[5] See: Leslie Kan and Chad Aldeman, “Eating Their Young,” TeacherPensions.org, July 7, 2015, https://www.teacherpensions.org/resource/eating-their-young and Jean-Pierre Aubry and Caroline V. Crawford, “State and Local Pension Reform since the Financial Crisis,” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, January 2017, https://crr.bc.edu/briefs/state-and-local-pension-reform-since-the-financial-crisis/.

[6] The IRS has separate safe harbor rules for defined benefit (DB) and defined contribution (DC) plans. This brief focuses on the rule governing DB plans. However, the rule governing DC plans has its own problems, and the two rules do not necessarily produce equivalent benefits for all workers. For more, see: Chad Aldeman, “Social Security’s Unsafe Harbor,” TeacherPensions.org, March 8, 2016, https://www.teacherpensions.org/resource/social-securitys-unsafe-harbor.

[7] Stephen C. Goss, Chief Actuary, Letter to Chairman Kevin Brady, October 4, 2018, https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/solvency/KBrady_20181004.pdf.

[8] See, for example: Aldeman, “Unsafe Harbor,” https://www.teacherpensions.org/resource/social-securitys-unsafe-harbor and Laura D. Quinby, Jean-Pierre Aubry, and Alicia H. Munnell, “Spillovers from State and Local Pensions to Social Security: Do Benefits for Uncovered Workers Meet Federal Standards?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, September 2018, https://crr.bc.edu/working-papers/spillovers-from-state-and-local-pensions-to-social-security-do-benefits-for-uncovered-workers-meet-federal-standards/.

[9] The original law also did not cover private-sector agricultural and domestic workers, but was amended to add those workers over time. See, for example: Larry DeWitt, “The Decision to Exclude Agricultural and Domestic Workers from the 1935 Social Security Act,” Social Security Bulletin 70, no. 4 (2010), https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v70n4/v70n4p49.html.

[10] William G. Gale, Sarah E. Homes, and David C. John, “Social Security Coverage for State and Local Government Workers: A Reconsideration,” Brookings Institution, June 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Download-the-paper-5.pdf.

[11] 26 C.F.R. § 31.3121(b)(7)-2(b).

[12] 26 C.F.R. § 31.3121(b)(7)-2(d)(i).

[13] 26 C.F.R. § 3121(b)(7)-2(e).

[14] For plans that average salaries over longer time periods, Social Security requires higher multipliers. For example, if the plan averaged the employee’s salary over 10 years, the annual benefit must be at least 2 percent times the employee’s years of service and average salary.

[15] For more on how a lack of Social Security coverage harms teachers, see Leslie Kan and Chad Aldeman, “Uncovered: Social Security, Retirement Uncertainty, and 1 Million Teachers,” Bellwether Education Partners, 2014, http://www.teacherpensions.org/sites/default/files/UncoveredReportFinal.pdf.

[16] 26 C.F.R. § 3121(b)(7)-2(d)(1)(i).

[17] To be fair, Social Security imposes its own requirement that workers have at least 40 quarters, or 10 years, of earnings in order to qualify for disability of retirement benefits. This works like a vesting requirement too, except that unlike a vesting period in a single retirement plan, Social Security is not tied to a specific employer or state, and more than 95 percent of jobs are covered by Social Security.

[18] Aldeman and Rotherham, “Friends without Benefits.”

[19] The regulation states, “An employee may not be treated as an actual participant or as actually having

an accrued benefit for this purpose to the extent that such participation or benefit is subject to any conditions

(other than vesting), such as a requirement that the employee attain a minimum age, perform a minimum period

of service, make an election in order to participate, or be present at the end of the plan year in order to be credited

with an accrual, that have not been satisfied.” See: 26 C.F.R. § 31.3121(b)(7)-2(d)(i).

[20] Dick Ingram, “Executive Director’s Report,” Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois, Winter 2015, https://www.trsil.org/sites/default/files/documents/winter15.pdf.

[21] The assumptions vary based on the worker’s gender and years of experience. See: CalSTRS Valuation 2017.

[22] From a retirement savings perspective, the worst possible outcome would be a worker withdrawing their contributions and failing to roll that money into some other retirement savings account. This “leakage” from retirement plans is quite common, but for a teacher without Social Security coverage, they might end up with no retirement savings and no Social Security.

[23] See, for example: Robert Costrell and Michael Podgursky, “Peaks, Cliffs, and Valleys: The Peculiar Incentives in Teacher Retirement Systems and Their Consequences for School Staffing,” Education Finance and Policy 4, no. 2 (2009): 175–211; Martin Lueken, “(No) Money in the Bank: Which Retirement Systems Penalize New Teachers?” Thomas B. Fordham Institute, Washington, D.C., 2017; Josh McGee and Marcus Winters, Better Pay, Fairer Pensions III. The Impact of Cash-Balance Pensions on Teacher Retention and Quality: Results of a Simulation, Report 15 (New York: Manhattan Institute, 2016); Ben Backes et al., “Benefit or Burden? On the Intergenerational Inequity of Teacher Pension Plans,” Educational Researcher 45, no. 6 (2016): 367–377.

[24] This figure represents an example, but as of 2017, the average salary for teachers with a bachelor’s degree and one year or less of experience earned $40,260. See Table 211.20 in T. D. Snyder, C. de Brey, and S. A. Dillow, “Digest of Education Statistics 2017 (NCES 2018-070),” National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, 2019.

[25] For Social Security, nominal earnings that are entered into the AIME are indexed to average wages through the Average Wage Index.

[26] This analysis assumes that workers enter their uncovered service with no prior years of Social Security earnings, but some workers will enter their uncovered service already qualified for Social Security, and those workers would immediately qualify for a Social Security benefit greater than what their pension plan is providing.

[27] The analysis here and throughout the paper uses the formula under the current Social Security Primary Insurance Amount. However, some critics may note that Social Security itself is projected to run a shortfall as soon as the year 2035. While that could conceivably lead to benefit cuts, the shortfall could also be addressed through a mix of tax increases and benefit cuts, and the precise combination of those are difficult to project, especially for different groups of workers. For that reason, we focused our analysis on present benefit values.

[28] The state also offers an early retirement provision of a reduced pension beginning at age 55.

[29] As before, the graph shows workers who enter their uncovered service with no prior Social Security earnings, but there are workers who enter their uncovered service who already qualify for Social Security.

[30] Nationally, about 55 percent of teachers begin their careers at or prior to the age of 25. In non-Social Security states, those figures range from 39.4 percent in California to 64.2 percent in Ohio. Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS), Public Teachers Data File 2011-12.

[31] As mentioned above, Rhode Island is a unique case in that the DB plan discussed here is part of a larger hybrid plan. But from the IRS’ perspective, the entire plan passes the safe harbor test thanks to this DB component.

[32] A report by the Boston College Center for Retirement Research estimated that about 45 percent of uncovered state and local government workers will eventually earn total retirement benefits, including Social Security, worth less than what they would have if they had been covered throughout their careers. In particular, Social Security’s progressive features help lower-income workers. See: Quinby, Aubry, and Munnell, “Spillovers,” https://crr.bc.edu/working-papers/spillovers-from-state-and-local-pensions-to-social-security-do-benefits-for-uncovered-workers-meet-federal-standards/.

[33] These figures do not include cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) because the IRS safe harbor rules do not consider them. However, if we were to include them here, they would drop the break-even points by 0-4 years, depending on the state’s normal retirement age, the starting pension benefit, and the size of the COLA.

[34] Aldeman, “Unsafe Harbor,” https://www.teacherpensions.org/resource/social-securitys-unsafe-harbor.