When I talk about pensions, I often cite a statistic about rising teacher mobility. It comes from Richard Ingersoll, Lisa Merrill, and Daniel Stuckey’s report on Seven Trends Transforming the Teaching Force: If you asked a teacher in 1987-8 how many years of experience they had, the most common answer would have been 15 years. If you asked a teacher in 2007-8 that same question, the most common answer would have been one year. Our schools are dealing with a lot more new teachers than they had in the past, and defined benefit pension systems aren’t set up to deal with this type of mobile workforce. Defined benefit pensions work best for a stable workforce, but they provide very little retirement security to early- and mid-career workers who leave before earning the sizable pension payments that come from working in one place for 25, 30, or 35 years.

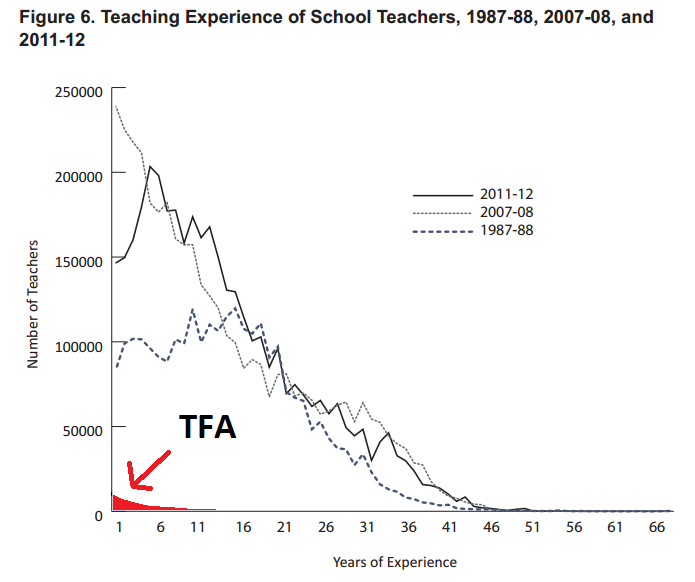

The teaching profession is not a stable workforce, and it's become less stable over time. When I talk about this trend, I like to use this graphic to illustrate what the changing teaching profession looks like:

Usually when I tell this story I’m talking about pensions, but rising attrition rates also have implications for the way we think about teacher preparation, induction, salaries, etc.

Inevitably when I cite this statistic someone asks about Teach for America. “Isn’t TFA, or a TFA-like effect, causing this rise in turnover?” they ask. The answer is no, or at least not very much.

The chart below uses the same data source as above, except that it overlays the teaching workforce of 1987, 2007, and 2011 on top of each other. I’ve added in the red at the bottom to show an estimate of TFA’s contribution to the teaching workforce.

TFA, although it’s the largest provider of new teachers in the country, is still tiny. Of 150,000 new teachers hired each year by school districts across the country, slightly less than 6,000 of them come from TFA. They have a 4 percent market share. TFA is big in relation to all other programs, but we have such a fragmented market in teacher preparation that they still represent a fraction of all new teachers hired.

What about TNTP and other Teaching Fellows programs? Altogether, adding up all their locations, the Teaching Fellows program trained an additional 2,182 teachers in 2012, or another 1.5 percent of teachers hired by districts. Taken together, TFA and the TNTP maybe prepare slightly more than 5 percent of new teachers hired by districts. These two organizations play an outsize role in our conversation about teachers because most of their placements are in large cities with large media markets, but they’re relatively small from a national perspective. Plus, TFA and TNTP didn’t even exist during this entire, longer period of rising attrition rates, so TFA and TNTP can’t be blamed for the changes.

If the trends in mobility aren’t caused by TFA or TNTP, what’s causing rising turnover rates? The simplest explanation is that teachers are part of a larger trend in the U.S. As our society as a whole has become more mobile, teachers have been part of that pattern. The Bureau of Labor Statistics followed all Baby Boomers throughout their working careers and found that the average Boomer held 11.3 jobs between the ages of eighteen and forty-six. Although turnover decreases with age, the median adult employee in the U.S. has about five years of experience with her current employer.

The recent recession slowed this trend for both the broader economy and for teachers. As the Ingersoll paper points out, during the recession districts slowed their hiring of new teachers while simultaneously laying off a large number of teachers, who were disproportionately in their early careers. But he predicts this will be temporary and that as the economy improves, districts will resume their previous practices and start hiring more new teachers. That will have implications across the education pipeline, and we need to have real, substantive conversations about what it means for the future of teacher preparation, induction, evaluation, compensation, and teacher pensions.