The Center for American Progress (CAP) recently released a report on teacher salaries. The report looks at the average base salary for teachers with 10 or more years of experience in all fifty states, comparing salary growth over time. The report finds that teacher salary growth is minimal. But as the National Review pointed out, this does not include the relatively high cost of pensions.

In the public sector, lower wages are supposed to be offset by more substantial retirement benefits. Public sector workers generally have more generous retirement packages than similar workers in the private sector. A public sector worker who stays an entire career will have more retirement wealth than their counterpart who stays an entire career in the private sector.

Retirement benefits are expensive, and these benefits are eating away at salary growth. Nationally, pensions eat up 16.3 percent of public employee compensation in states with Social Security, and 22.7 percent in states without Social Security. CAP featured a North Carolina teacher named Richie Brown. Mr. Brown and his district employer contribute over 20 percent of his paycheck toward the state retirement system. In California, the state teacher pensions plan has an unfunded liability of $74 billion. In order to pay down the current debt, the state increased pension contribution rates which are deducted from a teacher’s paycheck. Within the next decade, nearly 40 percent of California teachers’ total compensation will go toward paying down the pension plan’s unfunded liabilities. A report like CAP’s that looks only at teacher salaries would not see things like this, but rising pension costs are a significant factor keeping salaries flat.

Most importantly, while retirement benefits are meant to balance out lower wages, only a small percentage of teachers will actually experience the generosity of a full-career pension. Instead, the majority lose out and do not even qualify for minimal retirement benefits. All teachers pay the cost of higher pension contributions, but only a small fraction reaps the benefits. State policymakers need to consider whether loading public sector compensation at the backend is worthwhile, or whether more funds should be paid upfront through salaries.

Teacher attrition has increased over the past couple of decades, but attrition is not necessarily bad if the teachers who leave weren't performing well. What’s most problematic is the loss of an effective teacher.

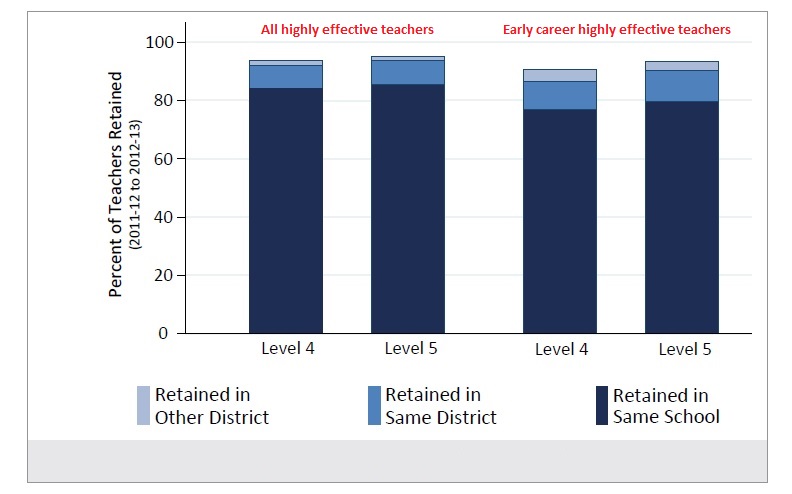

Tennessee recently released a report that examines teacher retention in relation to effectiveness. The report tracked teacher retention patterns alongside effectiveness levels from 2011-13, when the state first implemented its multiple measures evaluation system, the Tennessee Evaluator Acceleration Model (TEAM). Overall, teachers rated as highly effective tended to have slightly higher retention rates. Early career teachers with one to three years of experiences tended to have lower retention rates than teachers with more experience, including highly effective early career teachers.

The chart below shows the percentage of teachers who remained in the same school, the same district, or a different Tennessee district. The bars on the left show the retention rates of all highly effective teachers. The bars on the right show the retention rates of highly effective teachers who had only one to three years of teaching experience. Level 4 and 5 represent highly effective teacher ratings.

Retention Rates by Effectiveness

Source: Tennessee Department of Education, 2014.

Some Tennessee districts are much better at retaining highly effective teachers than others. The chart below shows the difference in district retention rates for districts who were able to retain highly effective teachers at a higher rate (teachers with a level 4 or 5 rating) and districts who retained lower performing teachers (teachers with a level 1, 2, or 3 rating) at a higher rate.

District Retention Rate Differences by Effectiveness

Source: Tennessee Department of Education, 2014.

What does this mean for school districts and policymakers? Districts need to consider policies that better retain early career teachers who have a higher probability of leaving, especially early career teachers who are already highly effective.

Policymakers can use this data to rethink teacher retention and quality in relation to the state’s pension system. Pensions have acted as a strong incentive for late career teachers nearing the prescribed retirement age to stay in the classroom, “pulling” teachers to stay in the system. But pensions do little to incentivize early career teachers to continue teaching, and instead punish teachers with fewer years of experience. What’s more, there is no evidence that teacher pensions raise teacher quality overall. Besides, it’s impossible for state-level pension plan to act as a recruitment or retention incentive for individual schools or districts. When it comes to teacher retention and quality, districts need to find local solutions.

If you work on the pension issue long enough you start to hear complaints that pension data are "out of date." Ross Eisenbrey, a Vice President at the liberal Economic Policy Institute (EPI), recently tossed out this allegation against a report from the conservative Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), but the claim is not a new one, nor is it unique to EPI. The same accusation is often flung at the non-partisan Pew Center on the States for their reports tracking state data on pension plan funding levels.

This is a flawed line of argument, and it says something about the pension debate that we even have to discuss it. But, since it continues, let's break it down why it's wrong:

- First, the CEI report cites the U.S. Census Bureau and states, "Due to lags in availability, the most recent data is from 2012." No one is cherry-picking their favorite data here: Eisenbrey and EPI are criticizing analysts using the most recent data from a trusted federal data source. The Census Bureau expects to release the 2013 version sometime this summer, but in the meantime it's factually inaccurate to call the 2012 data "out of date."

- Second, the federal government is not always a paragon of speed, but in this case the timeliness of its data is quite reasonable. The most recent federal data are for Fiscal Year 2012, which ended June 30, 2012. It can take individual states months to release their own reports--for example, it took the California State Teachers' Retirement System six months to release its own report this year. The Census Bureau takes another few months to compile all the state data into one, comparable report.

- Third, the most recent data collected by groups representing large public pension plans comes from Fiscal Year 2012.

- Fourth, even more recent projections have not found that funding conditions have changed materially over the last year. When the Boston College Center for Retirement Research attempted to collect 2013 data in May of 2014 (two months ago), it found that two-thirds of its sample of state and local plans still had not reported updated figures. Even with a partial dataset of the most recent data available from state and local governments, pension plan funding nationwide remained virtually unchanged.

We shouldn't allow this sort of quasi-defamation in our public dialogue. Trying to tarnish someone's work by lobbing "out-of-date" accusations should come with some proof that the researcher selectively chose data that bolstered their case or used data that are so old as to be meaningless. Otherwise, it's just an advocate using any means necessary to discredit data they happen to not like. Obfuscation is a nasty line of defense.

Taxonomy:On July 8, AARP and the Brookings Institution held a panel discussion on New Zealand’s government-sponsored retirement savings plan, KiwiSavers. KiwiSavers is a subsidized, voluntary defined contribution retirement savings plan. The New Zealand government implmented KiwiSavers in 2007 in order to increase retirement savings amongst the country’s citizens.

Before KiwiSavers, New Zealand residents relied on three main sources for retirement income: the country’s mandatory government retirement program “New Zealand Superannuation” or NZS (similar to Social Security in the U.S.), employer-provided pension plans, and private savings. KiwiSavers serves as a supplement to employer-provided pension plans, which not all citizens participate in, and NZS.

KiwiSavers participants can choose a specific scheme or plan and contribute 3, 4, or 8 percent (or none) of their paychecks to the program. Employers must contribute a minimum of 3 percent of an employee’s paycheck. All New Zealand residents under age 65 can participate in KiwiSavers (children can participate with their parents’ consent), and accounts move with the employee. Any financial service provider can apply to become a KiwiSaver provider, as long as they are approved and registered through the government. Thirty-one different providers currently offer KiwiSavers services.

KiwiSavers has several unique features. First, the program automatically enrolls participants. Rather than allowing citizens to default to non-participation, the program automatically withholds a 4 percent contribution rate from working citizens. Citizens can choose to opt out of the program, or alternatively, choose lower or higher contribution rates. People tend to exhibit a high amount of inertia when it comes to saving, and empirical research shows that automatic enrollment has a dramatic impact on participation outcomes. New Zealand was the first country to introduce a national auto-enrollment savings program (the United Kingdom is one of a small handful of countries to enact a national automatic enrollment savings program). Over half of the eligible population in New Zealand now participate in KiwiSavers, with 72 percent of 18-24 years old participating in the program.

A second key feature of KiwiSavers is its “kick start” financial incentive. To encourage participation, the New Zealand government gives a $1,000 tax-free lump sum to any new member’s KiwiSavers account. Members additionally receive a tax credit of over $500 if they contribute at least $1,000.

Although an initial evaluation found that KiwiSavers had only a marginal impact on overall national savings, the program is now conducting a longitudinal analysis on individual savings practices. Still, KiwiSavers has successfuly enrolled a growing number of participants and could be an example for the U.S. While current politics may prevent a similar national program at the federal level, states can look to KiwiSavers for designing their own government-sponsored retirement plans.

Matthew Di Carlo had an excellent post on teacher turnover over at the Shanker Blog a few weeks ago. Pulling data from the Teacher Follow-Up Survey (see Table 1 here), he created the graph below showing changes in teacher turnover over time. For each given year, the blue line represents the percentage of teachers who left the profession, the red line represents the percentage who move schools, and the green line is the sum of those two sources of turnover. For a variety of reasons, over the course of two decades total teacher turnover in the U.S. increased about two percentage points, from 13.5 percent to 15.5 percent.

Di Carlo spends some time analyzing the trend and discussing potential causes, so you should read his post. Here, I want to spend a bit of time thinking about the components of teacher experience levels and how they interact with pensions. Total Teacher turnover is the combination of several factors:

- Teacher mobility captures teachers who stay in the profession but change schools or districts. Mobility only affects pensions to the extent the teacher is moving into a new pension system. If a teacher changes schools or districts within the same state, they typically remain in the same pension system and continue accruing benefits. If they move across state lines (or across a pension boundary in districts with their own pensions, like St. Louis and Kansas City), they face potentially steep pension penalties.

- Teacher attrition captures the hundreds of thousands of individuals who work only part of their career in the teaching profession. They may or may not qualify for a pension at all or may qualify for such a small pension that it’s worth less than their own contributions.

- Teacher retirements are people who end their careers as teachers and begin collecting a pension of varying amounts depending on their salary and years of service.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the one-year turnover rates appear misleadingly low. They indicate the percentage of teachers leaving within one years’ time. But even low one-year rates become significantly amplified over longer periods of time. For example, assuming that the national average holds true for teachers at all levels of their career, a one-year rate turnover rate of 13.5 percent, as in 1988-89, converts to a 52.5 percent turnover rate over five years. The actual long-term turnover rate is probably a bit lower than this, but it's important to think about how short-term figures translate into longer-term effects. High turnover rates have consequences for schools, districts, and state pension plans, not to mention the individual teachers who leave.

Are state pension plans a recruitment or retention incentive for teachers? It's complicated, but many of the claims about the value of pensions don't stand up to scrutiny:

- Pensions could theoretically have some sort of blanket effect boosting recruitment and retention across the entire teaching profession. That argument may sound reasonable, but it's just as plausible that teachers don't know about or fully appreciate the thousands of dollars states and districts spend toward their pension each year. Most teachers will likely never see that money anyway.

- For early- and mid-career teachers, state plans themselves assume that actually qualifying for a pension has no effect on teacher retention. In our review of state turnover assumptions, we found no state where teachers time their departures based on when they qualify for a minimum pension. If pensions were really a retention incentive for these workers, we'd see evidence of teachers hanging on just long enough to qualify for a pension. We don't.

- Pensions do offer a retention incentive to late-career teachers. Teachers nearing retirement age do seem to respond to pension incentives, but this is a relatively small group of workers, and even large incentives barely change their behavior. For example, St. Louis spent $166 million on a pension enhancement that was worth tens of thousands of dollars for any teacher who stayed additional years. But other than teachers one year away from retirement, no other group of teachers changed their behavior, and the money had no effect on teacher retention.

- It's impossible for state pension plans to act as a recruitment or retention incentive for individual public schools or districts within a state. State pension plans offer all teachers a benefit that's distinct from all other workers. But by definition, a statewide pension plan that includes all public schools and all public school districts cannot provide any special recruitment or retention effect amongst those same schools and districts. School District A can't distinguish itself from District B if it's offering the same thing.

To sum up, the research on teacher pensions has been unable to find a recruitment effect, and prospective teachers rarely consider pensions as one of their top reasons for entering the profession. Researchers have found some retention effects for the small fraction of teachers who are committed to teach in one place for an entire career, but the teachers responding to this financial incentive may prefer to be doing something else instead. Two studies, one looking at macro-level impacts in Illinois and another looking at individual retirement decisions in Missouri, suggest that pensions may encourage some late-career teachers to continue teaching even if they're burned out or ready to do something else. In both studies, the pension plan appears to be slightly boosting late-career teacher retention, but it doesn't seem to benefit students.

At best, pension plans may provide a small boost in the retention of very late-career veteran teachers, but they have not led to increases in student achievement.