According to national data, four out of ten teachers will leave the classroom within five years. But turnover isn’t evenly distributed. The highest turnover happens in high poverty urban and rural public schools. In 2004-05, close to half of all public school teacher turnover happened in just one quarter of all public schools.

What’s more, turnover varies even within a district. A recent report from the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) tracked teacher retention across the Miami-Dade County Public Schools as one of several indicators correlated with teacher quality. NCTQ found that a sizeable portion of the county’s turnover took place in two particular low-income voting districts, and that many of the teachers who resigned left after only teaching a few years in the classroom. In the geographic region with the most turnover (voting district 2), over a third of all teachers who resigned had two or fewer years of experience, and over half had fewer than five years in the classroom. Florida makes similar statewide turnover assumptions about its teachers and assumes that over 60 percent of teachers will leave after 5 years. The graph below shows how teacher turnover differs within the Miami-Dade Public schools.

Teacher Resignations in the Miami-Dade Public Schools (by voting district)

Source: National Council on Teacher Quality, "Unequal Access, Unequal Results," 2014.

In terms of retirement, the Miami-Dade County Public Schools teachers in voting districts 1 and 2 are particularly vulnerable if they remain in the traditional state pension system. Any teacher that leaves the classroom before eight years will not qualify for a pension, and Florida assumes that roughly three-quarters of teachers won’t qualify. However, since 2002, teachers can choose to opt into a 401k-style retirement plan instead of a traditional pension. Teachers who choose the 401k-style retirement plan will automatically qualify for their account savings after just one year, and many teachers seem to prefer the plan according to one study. The 401k-style plan benefits are portable and better for shorter-term and mobile teachers, while the traditional pension plan are better for teachers who stay beyond eight years. Teachers in voting districts 1 and 2 would be better off choosing a 401k-style plan where they could leave with retirement account savings rather than nothing.

Having flexible plan options can give mobile teachers, especially in urban and rural public schools where turnover is high, more secure retirement benefits. School districts should additionally take a role in clearly explaining benefits options to teachers.

Last night Gina Raimondo, the Treasurer of Rhode Island and a champion of penison reform, won the Democratic nomination for governor of Rhode Island. A few quick thoughts:

- Pension reform can be good politics. Despite being a Democrat in state where President Obama took 63 percent of the vote, and despite heavy union opposition and spending against her, public polls showed strong support for Raimondo's leadership on pension issues. She brought facts and data to a knife fight, and she won.

- The pension reform legislation is still tied up in lawsuits, but it would be a good thing for both taxpayers and teachers. Once enacted, it's estimated to save the state $4 billion over two decades and would put the state's pension funds on a much more sound footing. Just as importantly, it would benefit the vast majority of teachers.

- There's still a lot of work to do. Even under the most generous assumptions and assuming the reforms pass legal muster, Rhode Island's teacher pension plan faces an unfunded liability of nearly $3 billion (it has saved only about 57 percent of what it has promised to pay out in benefits). We need more politicians like Raimondo who are willing to tackle pension issues and seek out solutions that are good for their state and good for their workers. Rhode Island just proved it's possible.

Taxonomy:The Empire Center and several other organizations have published a database of New York teacher and administrator pensions that lists the pensions and service years of every member. Contrary to its name, the highest pensioners in the New York Teacher Retirement System are not teachers. Fourteen out of fifteen of the top pensioners are former superintendents and one a research professor. None retired as public school teachers.

In New York, as in most other states, pensions are based on an employee’s years of service and final average salary, and teachers, principals, and superintendents all participate in the same retirement system. While not all administrators are former educators and only serve an administrative position for a few years, many have come into the profession as a former principal or teacher or other administrative pathway, often with years within the same state and local system. Long tenure in a single retirement system, paired with a high superintendent salary, equates to a very lucrative pension. In Missouri, a teacher who stays for a full career accrues $250,000 in lifetime pension wealth, a principal accrues over $360,000, and a superintendent $450,000.

In New York, one superintendent had close to 40 years of service in the Sewanhaka Central Schools, with only five years as superintendent. His annual pension totals $223,000, significantly more than a teacher with the same amount of experience would get. The highest paid retiree was the superintendent of the Commack school district, who has an annual pension of $325,000 (based on a final salary of over $655,000), the lifetime equivalent of over $5.5 million (a true pension millionaire). These are extreme examples that can occur because traditional pension formulas rely so heavily on final salary and total service years, and many superintendents have accumulated prior service years as teachers or mid-level administrators to count toward a full career. A career educator can work and pay into the retirement system with lower teacher or principal contribution rates for the majority of their working years and still qualify for a pension for the rest of their life based on their much higher superintendent’s salary.

What is the impact of these top officials on student achievement? One would hope that such sizeable pay and benefits would mean a significant boost in student outcomes. According to a new Brookings report, however, superintendents in Florida and North Carolina had only a minimal effect on student achievement. Compared to teachers, who have a larger impact on student achievement, superintendents had little. Administrators of course play a vital role in other aspects of managing a district, but they benefit disproportionately from the heavily back loaded nature of the traditional pension system.

Taxonomy:Dear Dana,

We don't know each other, but I've followed your work closely (and am looking forward to reading your new book on teacher politics). But I want to talk about your recent piece for Vox on Teach for America. You include a throway line about teacher pensions that's worth clarifying. In describing TFA's funders, you describe the Laura and John Arnold Foundation as a place:

where hedge-fund dollars are used to support causes ranging from criminal justice reform to reducing the costs of public pensions (including those held by veteran teachers).

Let's ignore the "hedge fund" dog whistle that you threw in and talk about pensions. In full disclosure, the Arnold Foundation also funds part of our pension work, including this site, but I want you to know that your characterization of them, and the work to reform pensions more broadly, is wrong in a seemingly mild but very important way.

There are some pieces of nuance that you should understand here. The most important thing to note is that no one is seriously advocating for reducing the pensions of any individual teachers or retirees. In many places that would be illegal (and even if it weren't, here at Bellwether we think it's not the right thing to do regardless). Teachers deserve to be paid what they've earned.

However, some states have granted protections to workers giving them the right, from their first day on the job, to accrue future benefits. Changing rules like that is not the same thing as reducing someone's pension. Worse, because these rules lock in benefits for existing workers, the only way for state and local governments to address funding problems is to target new workers exclusively. I believe we should protect the benefits that individuals have already accrued, but we shouldn’t tie the hands of state and local governments decades into the future.

We have a problem in our public discourse when "changes to a person's potential future pension" becomes portrayed as "pension theft," as it did recently in Illinois. Leglsiators were accused of "pension theft" for making prospective changes that only reduced pension benefits for those who had 20 years (!) or more before they were eligible to retire. Reasonable minds can disagree on what's fair warning, but isn't 20 years more than enough?

Finally, trying to change the structure of existing retirement plans is not even close to the same thing as going after retirees. Josh McGee, the vice president of public accountability at the Laura and John Arnold Foundation said just last week that, "Pension reform shouldn’t be about benefit cuts. That shouldn’t be the aim." McGee's own work has considered ways to shift expensive retirement costs into higher teacher salaries. When you call this "reducing pension costs," you're misleading readers into believing it's about budget concerns and screwing over workers, not about helping design something that might be better for teachers. Lost in the noise about pensions is the basic fact that the system doesn't even work very well for most teachers now.

That's why we need to have a more honest debate about issues like this, something I'm sure you as a writer can appreciate. Next time when you consider teacher pensions, I hope you'll consider a little more nuance. "Teacher Wars" is a catchy title for your book, but not everything has to be one. All the best,

~Chad

Taxonomy:The New York Times recently ran a long story about how New York City’s pension costs are 12 times higher now than they were in 2000 and how those rising costs are eating into other budget priorities. Randi Weingarten, the President of the American Federation of Teachers, responded with a short

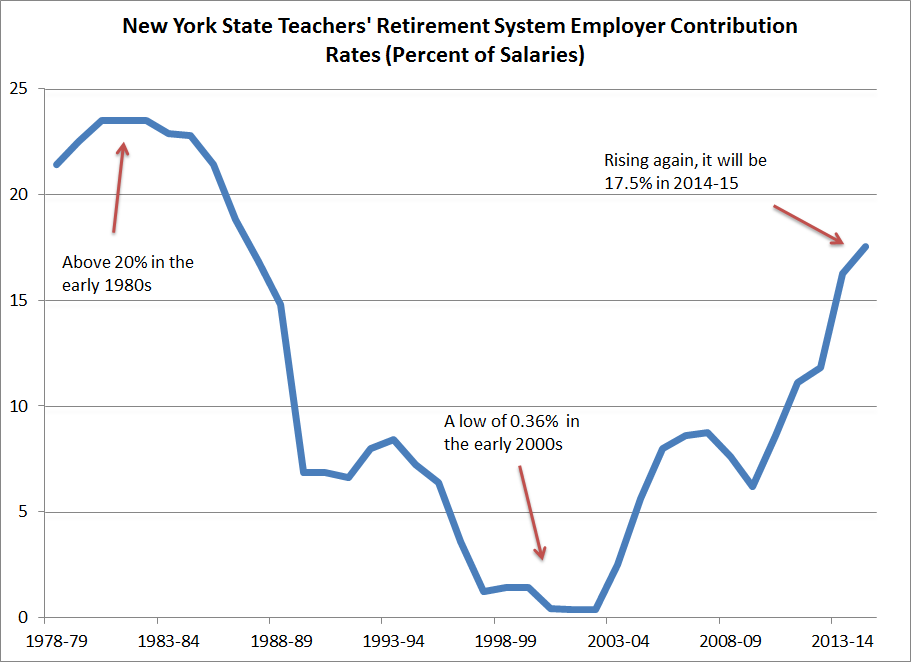

wave of her handletter to the editor that ignored the rising costs. Who's right?The Times did readers a disservice by focusing only on pension costs since 2000, but it is true that pension costs are affecting state and local budgets including schools. After the stock market boom of the late 1990s, state and local pension plans all across the country, including New York, cut their contribution rates as their assets swelled. The story of pensions since then has been one of rising contributions and increasing levels of under-funding, but that’s only part of the story. A more complete picture would show two things. One, New York's pension costs have fluctuated wildly (see chart below). Pensions appear artificially cheap during good times but impose steep and unexpected costs in bad times. Two, policymakers have enhanced pension benefit formulas over time, making the entire system more expensive. The result: public-sector workers, including teachers, now receive more of their total compensation in the form of benefits like pensions instead of base salaries.

Weingarten mentions the city’s recent strong investment returns but fails to note that even above-average returns haven’t been sufficient to restore the fund to solvency. And she tries to change the conversation by pointing out that many New Yorkers do not have access to an employer-provided retirement plan at all, leaving them worse off than unionized public sector workers. That’s true! It’s just not germane to the cost argument, nor is it particularly relevant to New York teachers (Weingarten's once and current constituents), many of whom won't qualify for retirement benefits themselves.

That's because any New York teacher who leaves before 10 years of service effectively gets no employer-provided retirement plan, just like many of their private-sector counter-parts. For every 100 New York teachers, 45 will leave without qualifying for a pension. They'll lose out on tens of thousands of dollars in retirement benefits.

This is ultimately where both the Times and Weingarten failed: Neither discussed the impacts current pension plans have on individual teachers. When the public is led to believe financial issues are the only problems with today's pension plans, financial issues will be the only problems legislators seek to address. They won't do anything to change the structure of retirement benefits to ensure that they meet the needs of today’s workforce.

Pension benefit increases were a painless way for politicians from both parties to provide something tangible to powerful interest groups without having to pay the costs immediately. A recent report provides empirical evidence to support this theory.

"The Politics of Pensions" by Sarah Anzia and Terry Moe compiles a unique data set looking at the politics surrounding pension legislation. By tracking pension legislation, partisanship, and media coverage from 1999 – 2011, the authors show that a dramatic shift in pension politics occurred before and after the recent recession.

Prior to the 2009 recession, states passed a number of laws enhancing pension benefits. Those laws expanded pension benefits, increased cost-of-living adjustments, lowered employee contributions, or made other changes to make retirement benefits more generous for public workers. Politicians could promise constituents pension increases, while pushing costs onto future generations and legislatures. From 1999 to 2008, states passed a total of 232 pension bills expanding pension benefits. After the economic recession, however, the political climate changed drastically. From 2010-11, 59 out of 63 pension bills issued some sort of reduction of pension benefits.

State Pension Legislation, 1999-2011

Pension legislation was primarily bipartisan up until the recent recession. Increasing benefits was a way for Democrats to respond to public sector constituents, and Republicans could support it as an issue that had little voter opposition. Before 2009, Republicans supported pension increases 92 percent of the time and Democrats supported benefit increases 97 percent of the time. After the recession, however, the politics on pensions changed sharply, and politicians increasingly voted along party lines. From 1999 to 2008, few pension bills were decided along party lines; of the bills passed in 2001, only 2 percent were decided along partisan lines by party unity votes. In 2011, party unity votes rose to 42 percent.

Partisanship on Public Pension Votes

Apart from pension beneficiaries, most voters weren’t aware of pension issues before the recession. The authors track the number of news clips related to state and local pensions using the New York Times as a proxy for media coverage. Before 2009, the media rarely covered pension issues. After 2009, however, the number of public pension news stories covered by the New York Times doubled. As seen in the graph below, the uptick in new stories happens at the same as the spike in partisanship in 2010.

Number of New York Times Storeis About State and Local Public Pensions

We traditionally see Democrats as supporters of public worker groups and Republicans as the antagonists striving to keep fiscal costs down. But before the recession, politicians on both sides of the aisle used pensions as an easy promise without consequences. Once states faced tough budget choices, then, the politics around pension legislation became increasingly partisan.

Figures Source: Sarah F. Anzia and Terry M. Moe, "The Politics of Pensions," December 2013.

Taxonomy: