We released a new TeacherPensions.org report today on teachers without Social Security coverage. Nationwide, more than 1 million teachers—about 40% of all public K–12 teachers—are not covered by Social Security, and our report takes a look at the negative consequences of this policy choice. We offer case studies on three hypothetical teachers to show that teachers of all experience levels would benefit from Social Security coverage as one part of a comprehensive retirement plan.

Read the full report here or a condensed PowerPoint version here.

The Boston College Center for Retirement Research has released an update on its National Retirement Risk Index, and the results aren't pretty. With a rising stock market and stablizing housing prices, we might expect a strong recovery in retirement savings and assets. Unfortunately, they don't seem to be having much effect, at least not for the majority of workers. That's mainly because 90 percent of all stocks are owned by the top one-third of the income distribution, and housing prices have risen only 6 percent, in real terms, since 2010. And with the median family actually earning less than they did 15 years ago, again in real dollars, it should be no surprise that retirement assets haven't grown.

The graph below (Figure 1 from the report) shows what this looks like across the age spectrum. Each line represents a given year, showing the ratio between wealth and income by age group. The yellow line, for 2013, suggests that across almost the entire age spectrum, Americans have fewer assets relative to their income than at any other time in the last 30 years.

It's not a pretty picture: In order to get back on track to enjoy a financially secure retirement. Americans will need to save more or work longer.

Taxonomy:Americans aren’t very good at saving. But apparently, workers in other countries aren’t either. To combat inertia, several countries (including the U.S. in the private sector) use a feature called automatic enrollment. Employers automatically place or enroll an employee into a retirement plan, while still allowing the employee to opt out of the plan. The purpose of this “nudge” is to encourage participation and increase retirement coverage for workers who otherwise would fall back into bad savings habits.

New Zealand and the United Kingdom have had particular success with state-administered auto-enrollment plans and received attention from AARP and Brookings, and more recently from the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; see Chapter 4).

Giving workers this prod can dramatically impact the number of workers covered by a retirement plan. New Zealand increased coverage from 15 percent of workers under age 65 in 2007 to nearly 65 percent in 2013. The United Kingdom increased their participation rates from 26 percent in 2011 to 35 percent in 2013, the first increase in a decade.

But reaching and maintaining high coverage depends on the design of the program and strategically communicating with and educating target populations. The OECD notes several design factors used in auto-enrollment plans, including the target population, opting-out window, contribution rates, financial and non-financial incentives, and communication strategy. Here are a few highlights:

- New Zealand sets the default contribution rate at 3 percent—with options to increase or decrease contributions)—but with the realization that most members will just choose the default. Just as an illustration, when New Zealand changed their original default from 4 percent to 2 percent, 62 percent of members who joined at the 4 percent rate continued to contribute at this amount even when the default was lowered. Still, New Zealand gives flexibility to members, allowing for “contribution holidays” where members can choose not to contribute if they are experiencing a time of financial stress or simply do not want to contribute for a period but wish to remain in the plan. In contrast to New Zealand, Chile had difficulty maintaining high coverage amongst its self-employed workers (73 percent chose to opt out despite auto-enrollment), and the OECD suspects that this is because of inflexibility in lowering the earnings amount that contributions were based on.

- To further incentivize workers, New Zealand gives a tax credit and a “kick start” of $1,000 to each individual account. The UK gives a 1 percent tax relief for qualified earnings to members. Paired with automatic enrollment, these incentives helped to keep members in the system.

- To educate workers about the national pension program, New Zealand created an extensive communications campaign that included TV, radio, and online ads, a website, and guides and presentations for employers and employees. In the UK, two government organizations were responsible for educating employers and employees, and created a website with planning tools and online portal as well as an advertising campaign. Government-sponsored surveys indicated high awareness amongst workers.

There’s a strong case for auto-enrollment in the U.S., and private companies are increasingly using the policy with very positive results. Public sector plans considering defined contribution, hybrid, or other alternative plans should capitalize on the benefits of automatic enrollment along with the design variables and communications strategy that go into an effective plan.

Taxonomy:In theory, defined benefit pension plans like those offered to 9 out of 10 teachers offer career public servants a steady stream of retirement income, adjusted for inflation as they age, that’s guaranteed to last their entire lifetime.

In practice, only half of teachers stick around long enough to qualify for any pension at all. Those that do must remain 20, 25, or 30 years in order to qualify for a pension worth more than their own contributions. And in a field with significant turnover, only a tiny percentage of teachers last a full career and qualify for the theoretical, idealized pension.

Unfortunately, too much of our debate about pensions focuses on theory rather than reality. The latest example comes from a report from William B. Fornia and Nari Rhee published by the National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS), in which the authors attempt to estimate whether pensions or 401(k)-style defined contribution plans are a “better bang for the buck.”

The entire report is based off a theoretical teacher who works for 30 years in the same pension system. Nowhere do they consider the “bang for the buck” of various retirement options for the vast, vast majority of teachers who don’t stay in the profession that long, let alone those who move between states.

Needless to say, they’re looking at a very small slice of the teaching workforce. On the most recent national survey from the National Center for Education Statistics, only 7.3 percent of teachers had 30 or more years of teaching experience. That figure includes teachers who split careers in multiple locations; if we backed mobile teachers out, the NIRS hypothetical would represent an even smaller amount of the teaching workforce.

What would happen if NIRS looked at different types of teachers and not just the minority with 30 years of experience? They would have to account for transition costs. In real life, teachers come into and out of the workforce, cross state lines, and attempt to transfer benefits from one retirement plan to another. They can face significant penalties when they do so, on the order of half of their pension wealth. The NIRS analysis assumes away these transition costs altogether.

In the fantasy world that NIRS has created, state pension plans do a bang-up job of delivering benefits to workers. That’s just not the reality of the world we live in.

Taxonomy:If we all live to 100, a scenario recently posed by The Atlantic, states and districts would likely face higher retirement costs in pension benefits, at least under current practices. But longer life expectancies could also open the door to policies that encourage work at older ages.

Longer worker life expectancies mean more pension payments from employers who promise benefits over a worker’s lifetime. When the Society of Actuaries updated their mortality assumptions, commonly used by pension plans to estimate future payments, they anticipated that pensions could expect up to a 7 or 8 percent increase in liabilities. This estimate is based primarily upon private plans, but teacher pension plans, which are made up of predominately female members (who tend to live longer), would also be impacted by an aging workforce.

Currently, teacher pension plans have relatively low retirement ages, encouraging teachers to spend more years in retirement and consequently draw more pensions payments. The median retirement age for a public school teacher is 58 years, compared to 62 years for the labor force as a whole. Meanwhile, pensions are structured to push out aging teachers by decreasing their overall pension wealth; every year that a teacher teaches beyond the normal retirement age is a year she forfeits pension payments. Traditional pensions basically encourage retirement at these earlier ages while punishing work at older ages.

There’s also a significant delay between actual trends in the workforce and when pension plans update their mortality assumptions. The mortality table preceding the most recent Society of Actuaries release was based on data collected from over 20 years ago. Actual life expectancies have risen considerably even in the last 20 years.

In the federal government, Social Security’s original retirement age of 65 was updated almost half a century after the initial act was passed (prompted mainly because of fiscal reasons). When Social Security benefits were first paid in 1940, the life expectancy for a male at age 65 was 78. It was 80 for a female. By the 1980s, the life expectancy for men increased by almost 2 years and over 4 years for women, where a women at age 65 was expected to live until age 84. Today, the Social Security Administration estimates that the life expectancy is 84 for a 65-year-old male and close to 87 for a 65-year-old female.

Policies like Social Security’s delayed retirement credit reward individuals who retire later with an increased percentage of benefits and encourage workers to work for more years. Some states also offer deferred retirement plans called DROP plans: teachers can “freeze” their pensions when they reach the normal retirement age. Instead of retiring, they can continue teaching and accumulate a separate DROP account of retirement benefits; or already retired teachers can return to the workforce without forfeiting their pensions. Rather than discouraging work at older ages, states can enact policies that will encourage workers to continue working for longer. The teaching workforce could benefit from the insights of veteran teachers, or second-career teachers who switched to teaching at a relatively older age.

There are mixed schools of thought on how much more life expectancy will continue to rise, and life expectancy itself varies by income. But even if we don’t all live to 100, the key takeaway for policymakers is that we still need to update our policies not just for the present workforce, but also the future one, and do so in a way that anticipates and rewards work at older ages.

Taxonomy:Back before Thanksgiving, we wrote about a new RAND report on the military's 20-year service requirement for eligibility to receive a pension. The report found that only 14 percent of enlisted personnel and 34 percent of officers remain for a full 20 years and qualify for a pension.

The report also analyzed the effects on retention efforts of offering such a back-loaded retirement plan. Not surprisingly, the current system provides little in the way of retention incentive to the vast majority of workers. Think about it. Imagine telling an 18-year-old Army recruity or even a 22-year-old officer that a nice pension awaits them…if they stick it out in the military for 20 years. The pension at the end of the tunnel may be comforting, but it probably isn’t enough to get them to stay, at least not by itself.

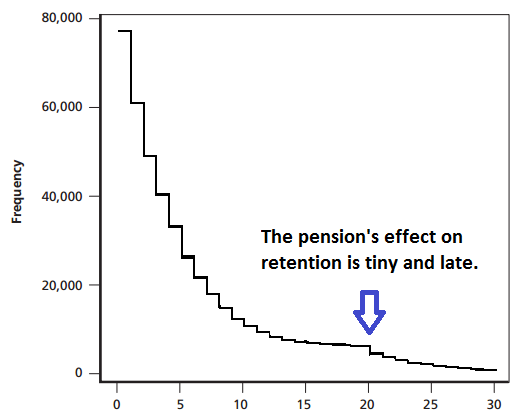

That’s exactly what shows up in the data. The graph below, modified from the RAND report, shows the number of enlisted personnel by the number of service years they have accumulated. As the graph illustrates, the Army recruits large numbers of enlisted personnel who mostly serve very short terms. Only a fraction of enlisted personnel make it to 10 years of service, let alone 20. For the vast majority of our Armed Forces members, the promise of a pension at 20 years means little. They're simply not willing to stick around that long for a pension.

That doesn't mean the pension has no retention incentive whatsoever, just that it can't possibly affect the majority of the workers. In the graph, the black experience line appears to flatten out around 17 or 18 years. Almost no one leaves then, because they might as well wait to hit the 20-year mark. And indeed, right at 20 years there's a small spike down of depatures. These are people who hung on just long enough to qualify for the pension. So the military's 20-year pension plan does have an effect on workforce retention; it's just tiny and comes too late to affect the majority of workers.

Teacher pensions have a very similar pattern, albeit one that's different in magnitude. Teachers, like members of the military, have very high rates of turnover in their early years. They may serve for a few years and then decide it's not right for them, but pensions probably don't factor very high into those decisions. (In fact, the pension plans themselves assume they have no effect on early-career teachers!) Later on, pension values rise dramatically as teachers near their state's normal retirement age. Just as with veteran military members, teachers know and understand their pension benefits and they tend to time their retirements accordingly.

As the RAND report models out, we don't have to stick with back-loaded pension plans that offer no benefits to the majority of workers. There are cost-effective alternative models that would offer more equitable, more portable benefits to all workers.