Yesterday, the New Jersey pension committee released a report proposing an overhaul of New Jersey’s pension and healthcare benefits. Although there are disconcerting aspects for existing workers that need to be addressed, unlike most reform proposals, the changes look promising for new teachers. Three big pension proposals that impact teachers from the report to highlight:

- Freeze benefits for all existing workers. Existing workers would keep all benefits already earned up until a set date. After that date, any benefits accrued will be under a new cash balance plan (see below). At retirement, workers would have a mix of pre- and post-freeze benefits.

- Move all new hires and existing workers (after the freeze date) into a cash balance plan. Cash balance plans pull elements from both defined benefit and defined contribution plans. In contrast to back-loaded traditional defined benefit plans, a cash balance—also known as a smooth accrual defined benefit plan—accumulates wealth at a constant rate. This means that early career teachers, who usually gain little to no benefits from traditional plans, can receive more benefits from the start. Unlike defined contribution or 401ks, workers are not responsible for making investment decisions, and hence do not bear all the risk, and can take their benefits with them as a lifetime annuity. The stickier issue will be whether existing workers can be moved into this plan, and the report has subsequently recommended passing a constitutional amendment allowing the modification of existing benefits.

- Give mid and late career workers additional pay credits or use a graduate pay credit scale. These carrots are offered as ways to make up for the loss in benefits that mid-career teachers may experience from switching plans. Normally, mid-career teachers who stay will receive a bigger bump in pension payments as they reach the end of their careers. Graduated pay credits would reward long-term service by paying workers increasing pay credits at various career milestones (i.e., a 3 percent of pay credit at 10 years, 4 percent for 20 years, 5 percent for additional years beyond 20 years).

Typically, pension reforms whittle down benefits to meagre levels without regard to effects on human capital, especially new hires. In New Jersey, a “non-forfeitable rights” statute protects existing workers from cuts. Meanwhile, any reform cuts have been issued solely to new tiers of teachers while benefits for existing workers, compounding existing inequities in the current system. New tiers essentially subsidize the benefits for past tiers in what the commission calls an “upside down wedding cake” system: multiple tiers of existing workers with protected benefits on top of a few tiers of newer workers who bear the brunt of the cuts.

New Jersey Teachers and State Employees Benefit Protections

Source: “Report of the New Jersey Pension and Health Benefit Study Commission,” February 2015.

While there are only a few winners and a much larger pool of losers in the current system, a cash balance plan would allow more teachers to gain secure retirement benefits from the onset of their careers. And while the decision to place existing workers into the plan and likewise the proposal to transfer oversight to unions rests on much shakier ground and likely to be challenged, the changes for new workers, if implemented well, could mean significantly better benefits for many of New Jersey’s teachers. After a history of pension missteps, New Jersey may be moving in the right direction.

*To read about the New Jersey pension commissions’ first report on the state health and benefit systems’ fiscal status, see here.

Yesterday Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner proposed changes to the state's $111 billion under-funded pension plans. Some of the media coverage I've seen isn't quite right. Here's the relevant text of Rauner's prepared remarks:

The pension reform plan in this budget will protect every dollar of benefits earned to date.

Let me repeat that, this is core of the issue: the pension reform plan protects every dollar of benefits that have earned so far.

What you’ve earned, you’re going to get.

And if you are retired, you get everything you were promised. That is fair and that is right.

But moving forward, all future work will be under the Tier 2 pension plan, except for our police officers and firefighters.

Those who put their lives on the line in service to our state deserve to be treated differently, and I believe the public will stand with me in this single case of special treatment.

This budget also gives employees hired before 2011 a choice to take a buyout option – a lump sum payment and a defined contribution plan in return for a voluntary reduction in cost-of-living adjustments.

A few things to note here:

1. Rauner is playing a little bit of politics. The Illinois State Constitution already protects every dollar of benefits earned to date, plus the right to earn future benefits. That's not a smart policy for the state, but his language is either a bit misleading or it hints at a desire to amend the state constitution.

2. The Tier 2 pension plan that Rauner mentions is extremely ungenerous to workers. It requires them to stay for more than 20 years just to have a pension worth more than their own contributions, and it's capped against inflation, meaning it won't keep up with rising costs. Illinois policymakers should instead be thinking of entirely new alternative plans rather than dumping all workers into the cheap, poorly designed Tier 2.

3. His proposal for an opt-out is a smart one. Research on Illinois suggests that workers may be willing to trade some upfront cash in exchange for lower retirement benefits. That would save the state money in the long run, but, because it's voluntary, it would not force any changes upon workers who didn't want it.

Taxonomy:Morgan Housel has a fantastic piece in The Motley Fool imagining a conversation between two hedge fund managers. It tells a pretty accurate, and damning, story of hedge funds' under-performance, high fees, and general lack of transparency.

Most people, and especially most teachers, don't personally invest in hedge funds. To them, hedge funds may be some sort of a distant and poorly understood creature of Wall Street. But one of Housel's hedge fund managers says that, "We're basically a conduit between public pension funds and Greenwich real estate agents." The other fellow says "Cheers to that."

Wait, what? Teacher pension plans are heavily invested in hedge funds? Yes, yes they are. Teacher pension plans and other public-sector pension funds have dramatically ramped up their investments in hedge funds and other forms of private equity over the last 30 years. In fact, pension funds in both the public and private sector are becoming some of the hedge fund industry's most dependable clients!

All this makes the politics of pensions very confusing. "Hedge funder" gets casually tossed out as a slur against anyone who works on ensuring pensions actually meet the retirement needs of workers. Advocates of the status quo use the specter of 401(k) plans to scare workers from believing that something better might be possible. And unions keep a "blacklist" against any hedge fund managers who personally support making changes from the status quo, even if those changes might run against their own professional interest.

Meanwhile, teachers and other public sector workers keep shuffling more and more of their retirement savings to Greenwich real estate agents. The conversation couldn't be more divorced from reality.

Taxonomy:When I was growing up I worked for a family-owned golf course. The owner had a dry humor and a loud voice, and whenever he'd hear a customer on a busy day who didn't want to wait in line ask how to get to a different, competing golf course, he would roar out "YOU CAN'T GET THERE FROM HERE!" and burst out laughing. It was a ridiculous assertion of course. But he wanted to keep his customers, and he didn't want to take time out of his day to explain how someone could back up and go to one of his competitors.

I think about my old boss every time I hear similar arguments about pension reform. A new brief from the National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS), an interest group representing large pension plans, tries to apply the "You can't get there from here" logic to pensions. Essentially what they argue is that it's impossible to end the current poorly designed defined benefit pension plans in favor of something better. Pension plan funding is so bad, they insist, that we must keep putting new people into it. We simply can't afford to do anything else!

If you take a step back, you realize this is crazy logic. Why would we keep putting new people into poorly funded, poorly designed retirement plans? As Andrew Biggs lays out for AEI, closing a pension plan does not change its unfunded liability. But it does mean we stop creating new unfunded liabilities, and it means new workers won't be subjected to the same, bad plan. We can offer them something better. We can get from here to there.

Taxonomy:Khan Academy is a non-profit, education organization that offers free, short instructional videos on a range of topics for students, teachers, and parents. The videos use step-by-step doodles and diagrams to break down complex content, and users also receive "energy points" for completing lessons which convert into special badges and track progress. Khan's videos have been viewed by more than 50 million users worldwide and translated into seven different languages.

See the video below (with over 25,000 views on YouTube) to hear Sal Khan, the founder of Khan Academy, explain public pension plans and how they become underfunded:

Taxonomy:There’s some good news for schools and teachers from the Center for American Progress (CAP): more new teachers are staying in the classroom after five years, up nearly 20 percentage points since 2007. The new finding uses data found in the 2007-08 and 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey, the Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Study, and 2012-13 follow-up study of the 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey released last fall. CAP found that 87 percent of new teachers stayed in the profession for at least three years, and close to 70 percent of new teachers stayed for at least 5 years.

Within the larger picture of teacher retention, it’s not clear whether these increases though are here to stay. The Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE) has tracked the teacher workforce over the course of several decades. CPRE finds a general trend of fewer years in the classroom overall, but with a recent uptick in longevity after the economic downturn. During the depths of the recession, employers stopped hiring and few people left their employment voluntarily. That was true across the broader economy, and it’s showing up in rising teacher retention rates.

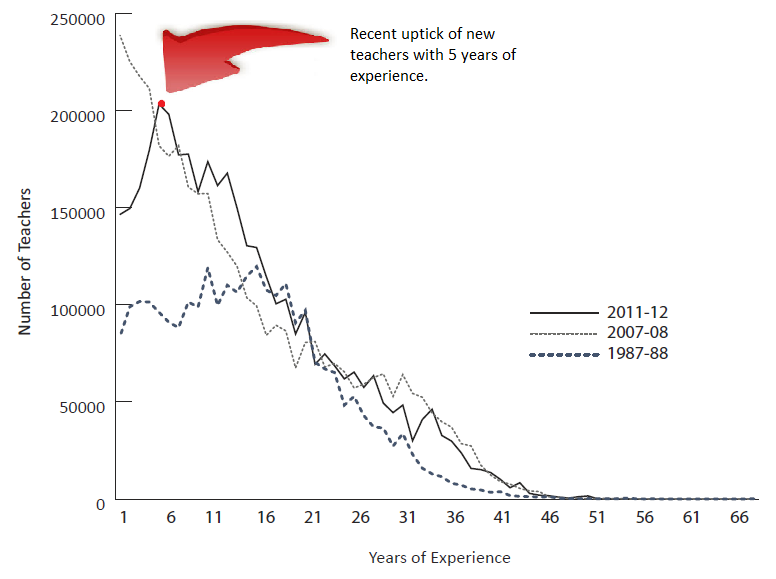

What’s less clear is how this recent trend fits in with a longer-term picture. In 1988, if you asked a teacher how many years of experience he or she had, the most common answer was 15 years. By 2008, the most common answer to the same question would have been one year, followed by two years. By 2012, this figure had crept up to five years. As the CAP report indicates, retention is higher and more teachers are deciding to stay into their fifth year. Time will tell whether this recent increase is just an effect of the recession or part of a larger structural change.

Teacher Classroom Teaching Experience, 1987 – 2012

Source: Richard Ingersoll, Lisa Merril, and Daniel Stuckey, “Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force,” University of Pennsylvania, April 2014.

But one thing is clear: despite this recent uptick, teachers who stick around for a fifth year still aren't going to be rewarded with a generous pension. In order to qualify for a pension, teachers must meet certain service or vesting requirements. Most states require a minimum of five years; 17 require teachers to work at least 10 years. Teachers who stay for a fifth year but then leave before year 10 would still miss out on qualifying for a minimum benefit in these states, despite their extra years of service (they would just receive a refund on their contributions and posssibly interest for each year). Even teachers who do qualify for a pension after just five years aren’t likely to see much in benefits because benefits are heavily backloaded. Rising retention means more teachers will qualify for some level of a pension, but it still won’t be very large and will actually cost the state more money.

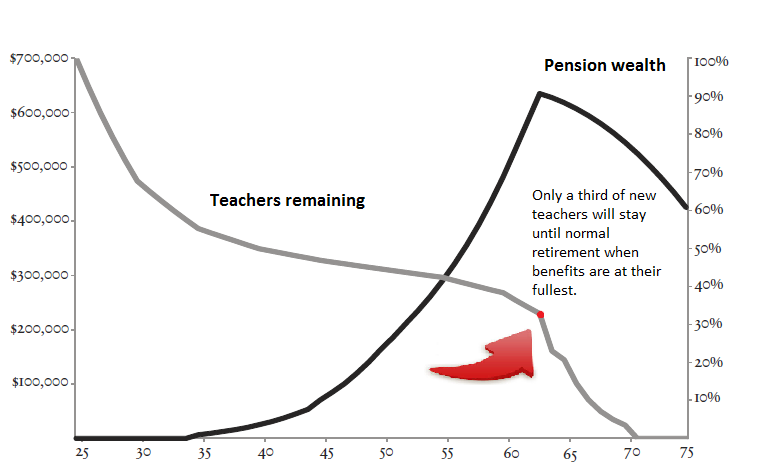

Teachers accrue very little during the first couple of decades of teaching. It’s not until they get closer to their plan’s normal retirement age—usually after 30 years or more for a 25-year-old teacher—that teachers begin to rapidly accrue benefits. The graph below comes from a paper by Josh McGee and Marcus Winters and shows the percentage of New York City teachers who stay in the classroom over the years and their corresponding pension wealth.

New York City Teacher Retention & Pension Wealth

Source: Josh McGee and Marcus Winters, “Modernizing Teacher Pensions," National Affairs, January 2015.

The gray teacher retention line begins high and drops significantly within the first ten years and continues to decline as time passes as fewer teachers stay in the classroom. Meanwhile, the black pension wealth line begins very low within the first two decades and quickly picks up more pension wealth as a teacher near retirement at age 63 and teaches beyond 30 years. A teacher earns roughly $3,500 per year of work for the first 20 years of service and then $30,000 per year for teaching years 30 through 38.

But only a third of new teachers will remain long enough to actually receive full retirement benefits. Also, New York City has a 10 year vesting requirement for any teacher hired after 2012. This means that even if a New York City teacher stays in teaching until her fifth year but leaves before year 10, she forfeits any rights to a pension benefit. Her retirement wealth will be relatively meager even if she stays beyond 10 years but leaves before 20 years.

It’s a good thing that teachers are staying in the classroom into their fifth year. States should reward teachers for making these choices. Alternative plans, such as a cash balance, accrue benefits smoothly and are not back-loaded. Rather than continuing blunt systems that only reward a small minority of teachers while leaving the majority of teachers with inadequate benefits, state and local plans should consider offering plans that more evenly distribute benefits.

Taxonomy: