An Illinois judge has ruled unconstitutional the state's 2013 law that decreased cost-of-living adjustments, capped pension amounts, and raised the retirement age for workers who are currently under age 45. For background, read my interview with Illinois state Daniel Biss, one of the co-sponsors of the 2013 legislation.

The state will appeal the ruling to the Illinois Supreme Court and what happens there is best left for legal minds. But what's clear is that this ruling is potentially very problematic for new teachers and those who aren't yet teaching. Because states like Illinois have constitutional protections that lock in benefits for existing workers, the only way for state and local governments to address funding problems is to target new workers. Nearly every state has created less generous plans for new workers, plans that will require new teachers to pay more money up front, remain in their jobs longer before they “vest” into the system and qualify for even a minimum benefit, and work longer before they retire with full benefits. This situation can’t last forever.

Illinois can't really cut much more. In 2010, faced with extreme under-funding of its pension system, and bound by the constitutional constraints, the state created a new plan for new workers. Robert Costrell and Mike Podgursky calculated what those benefits actually looked like for new, 25-year-old female teachers. The figure below compares the pension benefit offered to existing workers as of December 2010 (the dotted line) to the pension plan offered to new workers hired after January 1, 2011 (the solid line).

As Costrell and Podgursky write, "a 25-year-old entrant would not accrue positive net pension wealth until age 51; if she left teaching before then, she would be better off cashing out her contributions than leaving her money in for her pension." In a profession like teaching with relatively high turnover, only a fraction of teachers will stay this long. In practice then, Illinois is taking a no-cost loan from the majority of its new teachers. If the state has to cut costs in the future, it will have to create even less generous plans for future teachers. No one, including the courts, is looking out for them.

Last week was Veteran’s Day, and as we honor the security provided by those who served our country, we should also consider the retirement security of those who serve. While government initiatives through the GI Bill provide veterans with generous benefits such as education reimbursements, on-the-job training, and low-interest mortgages to help them successfully transition back to the civilian world, retirement benefits remain surprisingly inadequate for many of those who serve.

Alongside teachers and other state workers, the military is one of the few remaining occupations that still relies on a traditional pension. Like the plans offered to teachers, military pensions do not distribute benefits equally—severely shortchanging the majority of members—and their costs are high and unpredictable. The Department of Defense is now considering switching to a hybrid model that would combine a less-generous pension with a more portable 401k-style plan.

Currently, members of the Armed Forces participate in Social Security and a defined benefit pension plan. Similar to state pension plans for teachers and other government workers, benefits are calculated based on a formula that multiplies a member’s years of service by final average salary and a multiplier, 2.5 percent for military veterans. In order to qualify for this benefit, an Armed Forces member must serve a minimum of 20 years. According to a recent RAND report, 66 percent of officers and 86 percent of enlisted personnel will not stay long enough to receive these retirement benefits. The numbers are even steeper when separated by individual service branches:

Percentage Who Qualify for Military Pension Benefits Under the Current 20-Year Vesting Requirement

Within the Army, the largest branch of the Armed Forces, 93 percent of enlisted personnel and 68 percent of officers will not receive a pension. This is so shocking that it bears repeating: The majority of those who serve our country will leave with zero pension retirement savings.

According to RAND, the Department of Defense can significantly improve retirement security while saving between $1.8 billion and $4.4 billion dollars annually by adopting a hybrid retirement model. Rather than relying so heavily on a back-loaded pension, the recommended hybrid model has four streams of income: a smaller defined benefit pension, Social Security, a defined contribution or 401k-like plan called the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) that’s currently offered to civilian federal employees, and upfront bonuses for longevity paid out in cash. By decreasing the size of the pension benefit, members would receive an additional source of retirement income from the TSP and more upfront compensation through cash bonuses for certain longevity milestones (e.g., 12 years of service) or increased transition pay for those who serve for 20 years. The 20-year vesting period would remain the same for the traditional, smaller pension component. However, the TSP would have a lower vesting period of 6 years and would include an automatic 5 percent employer contribution, allowing more military members to leave with adequate retirement benefits.

According to the Department of Defense’s actuaries, the new model would not diminish the military’s capacity. Slightly more members would remain in the earlier years and slightly fewer members would stay after 20 years. Essentially, though, a hybrid plan would offer better benefits without altering who would serve.

The military remains one of the few federal agencies not already offering a more portable retirement benefit. Almost all federal workers today participate in a hybrid retirement plan, which itself replaced an outdated pension system and has provided employees with secure, portable retirement benefits. It may be time for the Armed Forces to follow suit.

Americans are not very good at saving money. The Wall Street Journal reported last week that adults under age 35 have a savings rate of negative 2 percent, meaning they're actually taking on debt in order finance their current consumption.

For most people, public policies are not to blame for their lack of saving. Individuals decide their own spending or saving habits, and they decide whether or not to participate in their employer’s retirement benefits, how much to save, and how to invest. Public policies set tax exempt savings limits and basic rules for individuals, but ultimately, individuals must make their own decisions.

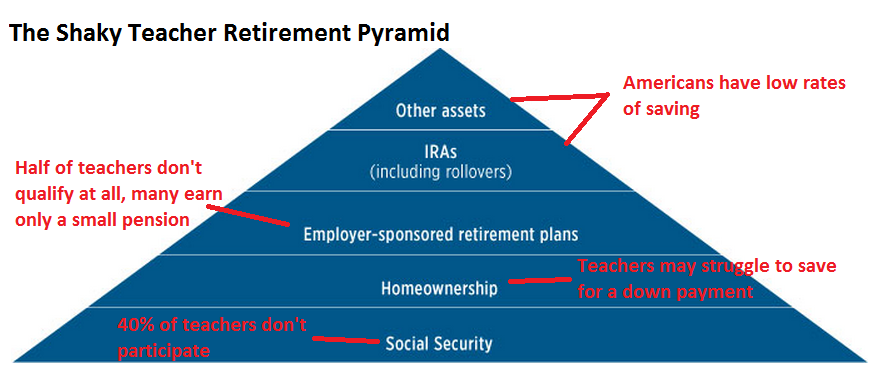

For teachers, however, insufficient savings can be blamed on bad public policy. To show how these policies harm individual teachers, I crudely annotated the Investment Company FactBook's Retirement Resource Pyramid.

At the base of the retirement pyramid for most workers is Social Security. For middle-income workers like teaches, Social Security may represent 40 percent of their retirement income. Unfortunately, 1.2 million K-12 teachers are not enrolled in Social Security, including a substantial portion of teachers in 15 states—Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Texas. These teachers are particularly vulnerable without the base of retirement security that Social Security affords all other American workers.

Next comes homeownership. For many households nearing retirement, their homes may be one of their most significant retirement assets. While we don't have national data on homeownership rates for teachers, we do know the average teacher salary is nearly in line with the median household income. Since teachers may be married or have other sources of income, we can assume they have slightly higher rates of homeownership than the 64 percent nationwide. Still, this would require them to be able to set aside enough spare income over their working years to save enough for a down payment, something that wouldn't be easy in every part of the country on an entry-level teacher salary.

Employer-sponsored retirement plans are the next-largest source of income for retirees. For teachers, that mostly means their state-provided pension plan. But current teacher pension plans are not meeting the needs of today's workforce. Half of all new teachers won't qualify for a pension at all, and many more will qualify for a pension that's worth less than their own contributions. A small minority of teachers will receive a fairly substantial pension, but, contrary to popular perception, most will leave their service with very little retirement savings.

At the top of the retirement savings pyramid are individual contributions to accounts like 401(k)s, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), or other savings vehicles. If we assume that teachers have the same savings rates as others at their income level, they are likely to have nothing or very little set aside in the way of personal retirement savings.

The end result is a pretty shaky retirement pyramid for teachers. At 3.3 million, public school teachers are one of our largest professions, and their retirement savings is our collective responsibility. We might hope that individuals will suddenly start to develop better saving habits, or we could start developing better public policies to support them.

Teachers naturally want to have a voice in how their schools are run. Through local collective bargaining agreements, teachers have a say in district salary schedules, the number and type of sick and personal leave, the length and timing of the school day and year, the number of students per classroom, the amount and type of support services offered to students, and the professional development provided for teachers. Teacher contracts can even include things like copy room protocols or the acceptable temperature of school buildings.

Teacher contracts include basically everything, that is, except pensions. School districts and teachers' unions don't negotiate on what the retirement benefit should look like or what level of benefit it should offer to various groups of teachers. Nor do they negotiate over how much the district should spend on retirement contributions. Some districts do negotiate over who pays the contribution--the district or individual teachers--but under statewide pension systems, decisions about benefit structures and contribution levels are all made by state legislators, state comptrollers or treasurers, or even unelected pension boards. Teachers have no more say over their pensions than the typical voter does.

The result of this odd dynamic is that districts are forced into spending large and growing shares of their budgets to pay for a benefit that teachers themselves don't fully value. Perhaps unbeknownst to individual teachers, this is happening across the country. While some teachers or districts may prefer lower expenditures on retirement benefits in exchange for higher base salaries, neither teachers nor local school districts are given that choice. School districts, including most charter schools, have no choice but to pay the rates set by the state legislature, even if they’d prefer to spend precious resources on higher teacher salaries, hiring more teachers, or making other critical investments in school services.

In other words, teachers might prefer a different arrangement than current state pension plans. But they don't really have a voice in those decisions.

Taxonomy:In Michigan, school funding has increased, but schools aren’t seeing much of the money. Instead, most of the funding increases are going toward paying off the state’s retirement debt.

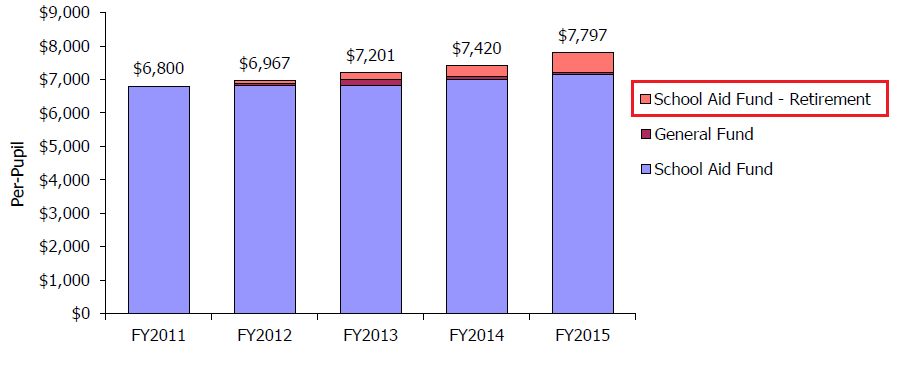

The Citizens Research Council of Michigan (CRC) released a brief documenting changes in the state's education funding over the past five years. The CRC found that state funding for K-12 education has increased by over $1 billion from fiscal years 2011 to 2015. Rather than going toward district resources, like curriculum or teacher salary, almost all of the increased funding is going toward paying off the state’s unfunded pension liabilities which now total over $25 billion. In 2015 alone, Michigan reserved $883 million in order for districts to pay off their employer retirement contributions.

The chart below tracks Michigan’s K-12 education funding in terms of per-pupil spending. The growing pink bars show how retirement funds are increasing, meanwhile the dark purple general fund bars are shrinking and the blue school aid fund bars remain almost stagnant.

State-Funded Per-Pupil Appropriations for K-12 Education, FY 2011 – 2015

Source: Citizens Research Council Memo, “Making Sense of K-12 Education Funding,” October 2014. Senate Fiscal Agency and House Fiscal Agency reports. Excludes early childhood and adult education funding.

In the face of growing pension liabilities, Michigan districts on average were required to set aside 16 to 18 percent of per-pupil spending toward retirement contributions over the past two years. This means for roughly every $7,000 allocated for a student, over $1,000 will go toward paying off pension obligations.

But Michigan isn’t the only state where retirement debt is eating into other school spending. In California, the state teacher pensions plan has an unfunded liability of $74 billion. In order to pay down the current debt, the state increased pension contribution rates that are deducted from a teacher’s paycheck. Within the next decade, nearly 40 percent of California teachers’ total compensation will go toward paying down the pension plan’s unfunded liabilities. Moreover, these costs are rising across the country.

It’s a good thing for states to pay down their pension debt. But in doing so, policymakers need to examine the costs and benefits of the system. Only a small group of teachers will actually reap the benefits of a full-career pension. In Michigan, the state assumes that over half of teachers will not qualify for even a minimum pension. The rising costs come with little reward.

What are the implications of last night’s midterm elections for pensions? I see three implications going forward:

1. Gina Raimondo, the Democratic governor-elect in Rhode Island, once again demonstrated that good pension policy can be good politics, too. Raimondo rose to national prominence as she championed reforms to the state’s under-funded and poorly structured retirement plan. She successfully ushered in a new plan that will save the state billions of dollars and improve benefits for the vast majority of teachers. Although the issue cost her union votes in the primaries, she became the first Democrat to win the state’s governorship in 22 years, even as many other Democrats struggled in other parts of the country.

2. Pension reform may be off the table in Pennsylvania. Incumbent Republican Governor Tom Corbett had championed pension reform for the last two years, but was unable to pass legislation despite a friendly Republican-controlled legislature. With Democrat Tom Wolf beating Corbett last night, the window for meaningful reform may close. The state still faces rising costs from its pension debt and a retirement structure that disadvantages the vast majority of the workforce, but Wolf has shown no interest in tackling those issues.

3. Pension reform isn’t done in Illinois. Bruce Rauner, the state’s newly elected Republican governor, made reforming the state’s under-funded pension system one of his top campaign priorities. We’ll have to wait and see whether Rauner’s support for a defined contribution plan for all new workers is primarily about costs and cutting benefits, or whether he’s willing to craft a well-structured plan that provides retirement security to all workers. If he’s serious about providing secure, portable retirement benefits for all workers, let’s hope he includes Social Security as one part of the solution for Illinois teachers.

Taxonomy: