The New York Times recently ran a long story about how New York City’s pension costs are 12 times higher now than they were in 2000 and how those rising costs are eating into other budget priorities. Randi Weingarten, the President of the American Federation of Teachers, responded with a short wave of her hand letter to the editor that ignored the rising costs. Who's right?

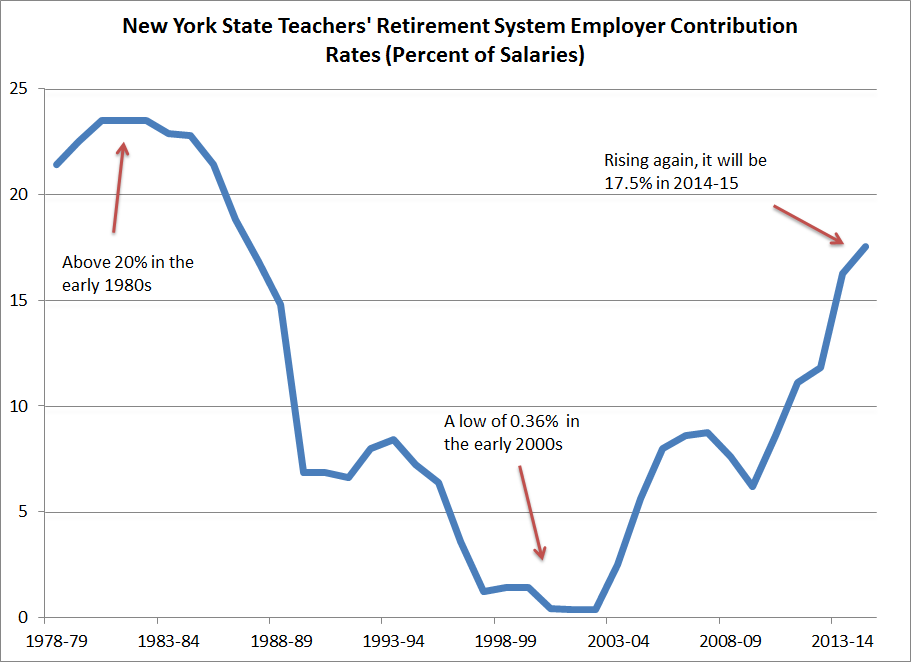

The Times did readers a disservice by focusing only on pension costs since 2000, but it is true that pension costs are affecting state and local budgets including schools. After the stock market boom of the late 1990s, state and local pension plans all across the country, including New York, cut their contribution rates as their assets swelled. The story of pensions since then has been one of rising contributions and increasing levels of under-funding, but that’s only part of the story. A more complete picture would show two things. One, New York's pension costs have fluctuated wildly (see chart below). Pensions appear artificially cheap during good times but impose steep and unexpected costs in bad times. Two, policymakers have enhanced pension benefit formulas over time, making the entire system more expensive. The result: public-sector workers, including teachers, now receive more of their total compensation in the form of benefits like pensions instead of base salaries.

Weingarten mentions the city’s recent strong investment returns but fails to note that even above-average returns haven’t been sufficient to restore the fund to solvency. And she tries to change the conversation by pointing out that many New Yorkers do not have access to an employer-provided retirement plan at all, leaving them worse off than unionized public sector workers. That’s true! It’s just not germane to the cost argument, nor is it particularly relevant to New York teachers (Weingarten's once and current constituents), many of whom won't qualify for retirement benefits themselves.

That's because any New York teacher who leaves before 10 years of service effectively gets no employer-provided retirement plan, just like many of their private-sector counter-parts. For every 100 New York teachers, 45 will leave without qualifying for a pension. They'll lose out on tens of thousands of dollars in retirement benefits.

This is ultimately where both the Times and Weingarten failed: Neither discussed the impacts current pension plans have on individual teachers. When the public is led to believe financial issues are the only problems with today's pension plans, financial issues will be the only problems legislators seek to address. They won't do anything to change the structure of retirement benefits to ensure that they meet the needs of today’s workforce.