States may be getting a deal for their teachers. The Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE) recently released a report on the changing trends in the teaching workforce. The authors—Ingersoll, Merril, and Stuckey—found seven trends in the data. The teaching force is simultaneously becoming: larger, older, younger and less experienced, more female, more racially diverse, and more consistent in academic ability. Important to the topic of state pension plans, the report findings mean that states have more retirees to pay for. But at the same time, states are hiring younger and more transient teachers who can be paid lower salaries and often leave before qualifying for a large or even moderate pension. It’s ostensibly a bargain for the state, but a loss for individual teachers.

The trends impacting retirement the most are the size, age, and experience of the teaching workforce. The CPRE report found that the teaching labor force has significantly increased from the mid-1980s and only recently tapered after the economic downturn in 2008. Within these increases, there has been a large increase in younger and less experienced teachers in the classroom.

The following graph shows the number of teachers and their ages:

Teacher Age (1987, 2007, 2011)*

Following the data lines over time, we see some big changes. Teachers in the 1980s tended to be older, where the most common teaching age was 41. A shift occurs however in the 2000s, and the most common teaching age decreases to 30. In addition, rather than simply one peak, there are now two peaks: one in younger teachers and one in older teachers. The teaching force is both older and younger or—in the authors’ words—“grayer” and “greener.” While “grayer” teachers with more years of service will cost the state more in salaries and retirement benefits, “greener” teachers with less service years will cost less.

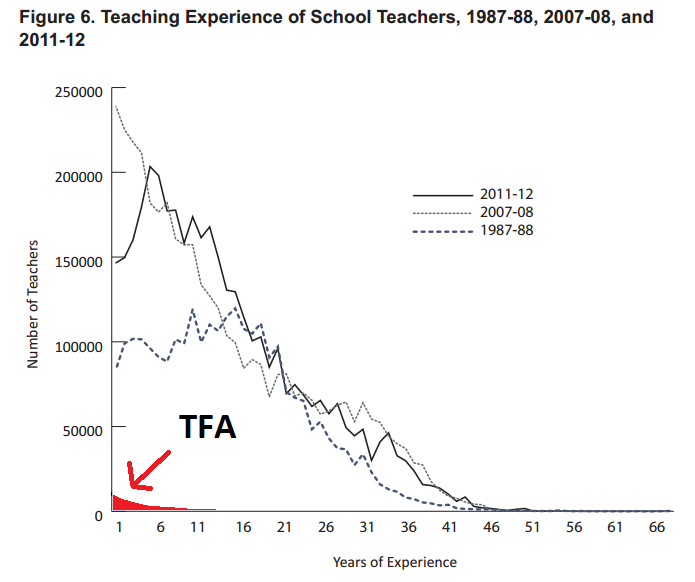

The next graph shows the number of teachers and their classroom experience.

Teacher Experience (1987, 2007, 2011)

As seen in this graph, there are dramatically more beginning teachers in our nation’s classrooms. In 1987-88, the most common teacher was in her fifteenth year. Compare this to 2007-08, when the most common teacher was a first year teacher, and the most common teacher in 2011-12 was a fifth year teacher. There remains a substantive number of older teachers, but the flood of new teachers into the workforce has pushed the modal or most common years of experience down. What's more, even during the recent recession, 41 percent of teachers left the classroom within five years. The teaching force has become more mobile.

What do these trends mean for state pension systems? An increase in veteran teachers means more teachers with higher salaries and retirement benefits. However, an increase in beginning teachers means lower salaries. Plus, beginning teachers are staying in the classroom for a shorter period of time. Put together, this means more “greener” teachers are paying into the pension system, and at the same time, leaving with little if any retirement benefits. This translates to cheaper costs for the state, but at the price of their retirement savings.

*Ingersoll, Merril, and Stuckey drew their research from the recently released 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS) and Teacher Follow-Up Survey (TFS) collected by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), part of the US Department of Education. The SASS data come from a nationally representative sample of 50,000 teachers and covers a 25-year period.

When I talk about pensions, I often cite a statistic about rising teacher mobility. It comes from Richard Ingersoll, Lisa Merrill, and Daniel Stuckey’s report on Seven Trends Transforming the Teaching Force: If you asked a teacher in 1987-8 how many years of experience they had, the most common answer would have been 15 years. If you asked a teacher in 2007-8 that same question, the most common answer would have been one year. Our schools are dealing with a lot more new teachers than they had in the past, and defined benefit pension systems aren’t set up to deal with this type of mobile workforce. Defined benefit pensions work best for a stable workforce, but they provide very little retirement security to early- and mid-career workers who leave before earning the sizable pension payments that come from working in one place for 25, 30, or 35 years.

The teaching profession is not a stable workforce, and it's become less stable over time. When I talk about this trend, I like to use this graphic to illustrate what the changing teaching profession looks like:

Usually when I tell this story I’m talking about pensions, but rising attrition rates also have implications for the way we think about teacher preparation, induction, salaries, etc.

Inevitably when I cite this statistic someone asks about Teach for America. “Isn’t TFA, or a TFA-like effect, causing this rise in turnover?” they ask. The answer is no, or at least not very much.

The chart below uses the same data source as above, except that it overlays the teaching workforce of 1987, 2007, and 2011 on top of each other. I’ve added in the red at the bottom to show an estimate of TFA’s contribution to the teaching workforce.

TFA, although it’s the largest provider of new teachers in the country, is still tiny. Of 150,000 new teachers hired each year by school districts across the country, slightly less than 6,000 of them come from TFA. They have a 4 percent market share. TFA is big in relation to all other programs, but we have such a fragmented market in teacher preparation that they still represent a fraction of all new teachers hired.

What about TNTP and other Teaching Fellows programs? Altogether, adding up all their locations, the Teaching Fellows program trained an additional 2,182 teachers in 2012, or another 1.5 percent of teachers hired by districts. Taken together, TFA and the TNTP maybe prepare slightly more than 5 percent of new teachers hired by districts. These two organizations play an outsize role in our conversation about teachers because most of their placements are in large cities with large media markets, but they’re relatively small from a national perspective. Plus, TFA and TNTP didn’t even exist during this entire, longer period of rising attrition rates, so TFA and TNTP can’t be blamed for the changes.

If the trends in mobility aren’t caused by TFA or TNTP, what’s causing rising turnover rates? The simplest explanation is that teachers are part of a larger trend in the U.S. As our society as a whole has become more mobile, teachers have been part of that pattern. The Bureau of Labor Statistics followed all Baby Boomers throughout their working careers and found that the average Boomer held 11.3 jobs between the ages of eighteen and forty-six. Although turnover decreases with age, the median adult employee in the U.S. has about five years of experience with her current employer.

The recent recession slowed this trend for both the broader economy and for teachers. As the Ingersoll paper points out, during the recession districts slowed their hiring of new teachers while simultaneously laying off a large number of teachers, who were disproportionately in their early careers. But he predicts this will be temporary and that as the economy improves, districts will resume their previous practices and start hiring more new teachers. That will have implications across the education pipeline, and we need to have real, substantive conversations about what it means for the future of teacher preparation, induction, evaluation, compensation, and teacher pensions.

According to a study released last week from the Urban Institute, nearly 80 percent of Rhode Island teachers will be better off under a new retirement plan adopted in 2011. Rhode Island legislators reformed the state retirement system with the adoption of the Rhode Island Retirement Security Act (RIRSA), which restructured the previous defined benefit plan into a hybrid plan comprised of both a defined benefit and defined contribution components. The law went into effect on July 1, 2012, and practically all working teachers were enrolled into the plan. State worker unions have since filed lawsuits against the legislation, and pending mediation for a settlement proposal could alter certain provisions in the plan.

Before 2011, teachers participated in a traditional defined benefit pension plan. The old plan calculated pension benefits by multiplying final average salary by total number of service years and a multiplier determined by the number of service years. Teachers who worked for a minimum of 10 years could participate in the system and receive full-retirement benefits at age 65 (or after 29 years of service at age 62). Teachers who met retirement service requirements before July 1, 2005 were vested in “Schedule A”; teachers meeting service requirements after July 1, 2005 were vested in “Schedule B.”

Under RIRSA, almost all working teachers are now enrolled in a two-part hybrid plan. The hybrid consists of a less-generous defined benefit component than the one found in the old pension system, as well as a defined contribution component similar to the 401(k) plans found in the private sector. Teachers contribute 3.75 percent to the defined benefit portion of the plan and 5 percent to the defined contribution portion of the plan. The state will contribute 1 percent to the defined contribution portion of the plan.

How does the new plan affect teachers? The Urban Institute recently issued a report evaluating the impact of the hybrid plan for Rhode Island’s teachers. While the payment for a defined benefit is determined in advance (hence the benefit is “defined”), variable investment returns leave the payment of a defined contribution unknown. The Urban Institute ran simulations of 1,000 different investment return scenarios to determine the probability or likelihood of a teacher’s defined contribution wealth. The study found that nearly 80 percent of teachers would receive greater benefits under the hybrid plan. Particularly, teachers who serve less than 30 years are more likely to receive increased benefits under the new hybrid plan. The median increase in annual benefits is $5,000 for teachers who teach for 10 to 14 years, and a $7,800 increase for teachers who teach for 25 to 29 years. All teachers who serve less than 10 years will receive greater benefits due to the defined contribution portion of the plan. The odds of increased benefits, however, decreases for teachers with thirty or more years of service. Teachers with thirty or more years of service have only a 50-50 chance of increased benefits. Teachers with thirty-five or more years of service have only a 30 percent chance of increased benefits; these teachers could lose up to $11,500 a year under the new plan.

The following chart from the report compares annual pension benefits from the old Schedule B plan and new plans.

Annual Pension Benefits

Old Plan (Schedule B) vs. New Plan (Hybrid)*

The first set of solid blue bars shows the annual defined benefits in the old system. In the old system, pension wealth is back-loaded and accumulated mostly in the later service years. Teachers with thirty-five years of service receive the greatest benefits with lifetime payments averaging $50,000 a year. Teachers with 10 years of service receive an average benefit of less than $5,000. Teachers who leave the system before 10 years of service are not eligible for a pension and only receive their contributions without interest.

The next set of red-blue bars shows the mean or average yearly benefits in the new system. While the hybrid plan’s defined benefit is smaller than the old plan, in combination with the defined contribution plan, total hybrid benefits exceed the old plan for potentially all groups of teachers. Teachers in the earlier years receive substantively more in benefit payments, particularly for teachers who teach between 10 to 20 years of service.

In the old system, only 15 percent of teachers stayed in the classroom long enough to garner a high pension while the majority of teachers received minimal or no retirement benefits. Unlike the old plan, the hybrid plan provides greater retirement security for teachers who teach for twenty years or less, while still providing comfortable retirements for teachers with more service time. In other words, the researchers found that more teachers would likely benefit from the new system.

Rhode Island has been in the midst of a settlement agreement over RIRSA. The settlement agreement, if passed, would keep the same hybrid plan but increase the employer contribution in the defined contribution portion for teachers who reach 10 to 20 years of service. The Rhode Island Superior Court recently ordered the state and plaintiffs to return back to mediation, where the future of the plan will yet to be determined. The Urban Institute report suggests most teachers would be better off if they preserved the fundamental elements of the new plan.

*From Urban Institute authors’ calculations from plan documents and actuarial reports. Estimates are for teachers hired in 2014 at age 25 who earn the average salary among plan participants for their age and years of service. The analysis assumes that hybrid plan participants annuitize the balances from the DC.

Dave Low is the Executive Director of the California School Employees Association and the Chairman of Californians for Retirement Security, a coalition of 24 unions including the California Teachers Association and the California Federation of Teachers. Low has been a leading advocate for the state’s public pension plans and actively pushed back against a proposed statewide ballot initiative that would have changed California’s constitution to allow state and city governments to make prospective changes to retiree benefits.

To better understand the issues around California’s pension plans, I spoke with Mr. Low. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Chad Aldeman: California's pensions are significantly under-funded. As of June 30, 2012, the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) was only 67 percent funded and had liabilities that were almost $71 billion more than its assets. CalPERS, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, was underfunded by $76 billion. Can you talk about how we got here?

Dave Low: First of all the term “severely underfunded” is probably not very accurate. CalSTRs at 67 percent is underfunded, but in terms of actuarial analysis, a funded plan would be a plan that’s between 80 and 100 percent funded. So to say that all plans are severely underfunded is not completely accurate.

The main reason that we got here is because of the economic downturn and the abuse and fraud that went on on Wall Street that ended up sapping money from everyone’s pension plans as well as everyone’s 401(k)’s. During that crisis, plans lost approximately 30 to 40 percent of their assets which is a devastating hit. Individuals lost that amount or even more in their defined-contribution plans. So prior to the economic downtown, CalSTRS and CalPERS and most of the pension plans were more than 100 percent funded.

Aldeman: How do we unwind today’s under-funding problem? I know that both the large California state pension plans had a pretty good year of investment returns last year and exceeded their targets. Can we grow our way out of this problem? Are we likely to get back to 100 percent funding in the near future or anytime soon?

Low: I don’t think we’re going to get there anywhere in the near future, but I don’t know what might happen in the long-term. If you look at the past, in 1980, CalPERS, CalSTRS, and most of the California funds were at a funded status of 50 to 55 percent. Then over the next 20-25 years, they achieved a super-funded status at over 100 percent. So it’s possible to get back to 100 percent or greater over time, but I don’t think anyone would say that that’s going to happen over the short-term. It’s just not the way it works. Unless they put their money on red in Vegas and won.

Aldeman: Do you think changes need to be made to the existing plans, or do you think that prudent funding and more consistent investment returns will return them back to solid funding?

Low: Well, the legislature has already made changes to the plans. This past couple of years ago there have been changes to all plans in California. I don’t see any other dramatic changes that need to be made going forward.

Essentially, CalSTRS is in the situation they are in primarily because of under-funding, in addition to the fact that they lost so much money in the economic downturn and the debacle on Wall Street. They don’t have the legal authority to increase the rates on a year-to-year basis. So they are on a fixed-funded status and the legislature is working on that. I think it’s going to require several things to get CalSTRS back on track: legislatively, they probably need to increase the amount of money going into the fund. Then they also have to meet their mark in terms of their investments over time.

Aldeman: What about the legal protection known as the “California Rule”, which has been the subject of an attempted statewide ballot initiative recently? It grants employees the right to accrue future pension benefits that they haven't worked for yet as if a contract exists going forward. In practice, this might mean that an employer who wants to cut costs on retirement benefits must do so solely for new employees. Is this fair to new workers, or is this just a consequence of preserving that contract between existing employees and employers?

Low: I think it’s fair to the workers that are there, and I think that if employers determine that pensions need to be cut for new workers, new workers know what they’re getting when they come in. So the law is fair to both sides.

Aldeman: Your organization works to protect the retirement security of a diverse group of employees--firefighters, police officers, teachers, school employees, and other public employees. Do you think all of these workers should have the same type of retirement system, or do different groups of workers need different types of benefits?

Low: I think that yes, it doesn’t make sense for everyone to have the same thing because there are different types of jobs and different types of systems. For example police officers, firefighters, and teachers, generally are not in Social Security, so their formulas are reflective of that difference. Most other employees are in Social Security. I think the best thing to do is to have pension systems that are tailored to the needs of the employees and the ability of the employer to recruit and retain qualified people.

Aldeman: It’s not commonly known that all public-sector workers are not in Social Security. In our recent paper, we looked at California’s turnover assumptions and estimated that one-third of teachers won’t reach California’s 5-year vesting requirement and thus won’t qualify for a pension. These teachers won’t receive Social Security either. What steps if any should be taken to ensure their retirement security?

Low: I think that everyone should have retirement security, whether you work in the public sector or the private sector. If you work a career, you should be able to not be in poverty once you retire. The same is true for all the teachers who leave the profession. I don’t know where they go. Some of them go to the private sector, some of them might go to another public sector job. Wherever they go, I do know that this trend towards taking away pensions and putting people in 401(k) plans is creating a generation of people who are starting to retire now who don’t have anything saved up for retirement. I don’t think that’s good for people and that’s not good for society.

Aldeman: One of the things we wrote about in our paper is that there are a large group of new workers who aren’t staying in the pension system long enough to qualify for a pension, so they lose out on a pension, and they will also often lose out on employer contributions or interest on their own contribution. Are you worried at all for their retirement security?

Low: For the workers who don’t vest, they do get their own contributions back with interest. So they don’t lose out on the interest. If they don’t work for five years, then they do leave the employer contributions in the system. I think that that’s the way the system is set up; I don’t think it’s extremely unfair. If they fail to vest, it’s not their money. If they come back into the system, if they leave their money in the system, they can come back and work and eventually vest, or at least they can get their money back with interest. The bigger concern is for those employees and where they go next and what type of system is available to them in their next job.

Aldeman: Defined benefit pension systems work best for a stable workforce, for someone who says in the same pension system for an entire career. But American society has become more mobile over time, and recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics suggests the median adult employee in the U.S. has only five years of experience with their current employer. Do you think traditional defined benefit plans still support this type of workforce? If not, what would we do about it?

Low: Well, they can. I think that the problem is not the design of defined-benefit pension systems; the problem is that people are just getting less and less security all around. Social Security is constantly under attack. Social Security was designed as one of those backstops. The traditional formula is the three-legged stool, Social Security being one leg, savings being another, and then a pension plan being the third. Generally speaking, that system still works, even in a mobile workforce, if you have plans in place that are adequate. But when you move from employer to employer, some employers don’t even provide a sufficient or a matching 401(k) plan. And if Social Security is weakened, then nothing is going to work for those people.

Aldeman: What about those people who work for ten or 15 years in a defined-benefit plan that aren’t fully reaching the normal retirement age, and not staying for a full career, and not in Social Security either? Do you think that the current system is serving them well?

Low: If you’re not in Social Security, and you only work for 10 years, there’s no system that’s going to work well for you, unless you’re making a lot of money. The reality is in order to retire, with some level of financial security, you have to put in a full career of work. If you don’t have Social Security, then you have to make up for that, potentially one-third of your income, by making more or saving more. So again, I don’t think it’s the system. There are certain people based on their circumstances that they’re not going to make it through retirement, they’re going to run out of money. If you don’t have Social Security, in a fifteen year career, the average worker is not going to save up that much money. If you have no pension, or a very small pension, you’re going to be in trouble.

Aldeman: Yes, my question was about people who are working another job but only worked ten or fifteen years toward a pension. Let’s say they teach for ten or 15 years, and then they go into the private workforce. So they don’t have a large pension from the public system, they have a modest one, and then they don’t have Social Security for those years either.

Low: That person if they worked another career in the private sector then they would have Social Security from the private sector. They’ll have whatever they’ve saved up during all those years, and they’ll have a relatively modest pension. If you worked for fifteen years as a teacher, you’re going to get 30 percent of whatever you were making for the rest of your life. I would say for having worked in the public sector as a teacher or something else, you’re going to be better off than another worker who didn’t have that pension.

Aldeman: Some states have allowed public sector employees to choose what type of retirement plan they want to enroll in, whether it's a defined benefit plan or a defined contribution plan. California has this to some extent, they allow some part-time teachers to opt into a cash-balance plan, but they automatically enroll full-time teachers into a defined-benefit plan. Would you support allowing employees to make a choice or expanding that choice to more types of workers?

Low: It’s depends on what the choices are. If you’re going to give people a variety of solid options, we would, of course, consider giving people choices. But if you’re going to give them a choice between good and very bad options, we don’t think that’s a wise way to go.

Aldeman: In addition to traditional defined-benefit plans, what other good options could you foresee?

Low: I’ve seen hybrid plans that offer a combination of defined-benefit and defined-contribution elements. Even in a defined-contribution plan, the choice of whether it’s good for you or not is going to depend on, number one, how much is your employer going to put in? Because if the employee is putting in all the money, or the vast majority of it, that’s probably not going to end up being very good for them. What are the investment options available? What kind of education is provided? Because most people aren’t very financially savvy, and they often make very bad choices. To me, you have to provide a choice of well-thought out and well-designed plans.

The New York Times recently covered a story about a 57-year-old woman, Gail Ruscetta, who switched careers to become a teacher in Virginia. Retirement security is important for all workers but is particularly salient for individuals nearing retirement age and moving into a second career in their late fifties. Unfortunately for teachers like Ms. Ruscetta, most state pension plans are designed primarily to support the retirement of teachers with a much longer time to serve. Her retirement benefits will be relatively modest in comparison.

As a teacher beginning in 2012, Ms. Ruscetta is covered under a traditional defined-benefit plan. The traditional pensions benefit is calculated by multiplying a teacher’s final average salary by a 1.7 multiplier by years of service. After five years of service, Ms. Ruscetta will qualify for a yearly pension benefit of roughly $4,600, or about $83,000 for her entire retirement. Benefits earned at this stage of a career are unlikely to be sustainable by themselves.

Ms. Ruscetta coincidentally entered the teaching workforce right at the cusp of reform. In 2012, Virginia passed an overhaul of the state retirement system. Under the new law, teachers hired on or after January 1, 2014 must enroll in the state’s hybrid plan. The state’s new retirement plan consists of a less-generous defined-benefit component than the one found in the old pension system, as well as a defined-contribution component similar to the 401(k) plans found in the private sector. Teachers hired before January 1, 2014 retain the traditional defined-benefit pension plan or can choose to opt into the new plan. Had Ms. Ruscetta began working in the 2014-15 school year, she would have been automatically covered under the new plan.

As a hypothetical, let’s look at how retirement earnings under the traditional plan compare to the new hybrid plan. The hybrid plan has two streams of retirement benefits. Assuming she contributes the maximum 5 percent (which the state matches at 3.5 percent) and a 6 percent investment rate, the hypothetical teacher would accumulate around $26,500 after five years in the defined-contribution portion of the plan. She could receive the $26,500 as a one-time lump sum, spending the amount however she chooses. In the defined benefit portion of the plan, she would receive a yearly benefit of $2,700. This $2,700 is an annuity, meaning that she would receive $2,700 on a yearly basis beginning at age 65 and each subsequent year of her life for a cumulative benefit of about $49,000 (unadjusted for inflation).

Retirement Benefits (With 5 Years of Service)

The traditional defined-benefit plan would provide Ms. Ruscetta with a higher annuity and total retirement benefits than the new hybrid plan, but only if she stays at least five years. If Ms. Ruscetta (or any teacher) leaves before five years, she would relinquish rights to a pension altogether, and leave with just her original contribution and accrued interest. The hybrid plan, in contrast, allows new teachers to retain 50 percent of the employer contribution after two years, 75 percent if they leave or move after three years, and 100 percent after four years.

The state retirement system estimates that half of all teachers who begin teaching at age 25 will leave the system after five years and 73 percent will leave before 10 years. The state estimates higher retention rates for teachers entering the classroom at older ages, but they still have relatively high turnover. For teachers who enter Virginia public schools at age 55, the state estimates that 64 percent will remain in the classroom after five years and 50 percent will remain after 10 years. Given these retention statistics, the new hybrid plan provides transient and short-term teachers greater retirement benefits (as opposed to just their own contributions). Whether the hybrid plan itself could create an incentive for increased turnover is up for debate and an area for research.

What does this all mean for Ms. Ruscetta? We certainly hope the odds are in her favor to stay in the classroom as long as she likes, but it’s understandable that a 55-year-old may want to retire at a reasonable and comfortable age. While Ms. Ruscetta’s pension benefits greatly increase with additional service years (her annuity would rise to $11,000 after 10 years or $30,000 after 20 years), her chances of remaining in the classroom become slimmer and slimmer with each passing year. Plus, at some point she has a diminishing return because each year she continues working is a year she can’t enjoy retirement. Only a small percentage of teachers like her stay in the classroom for long enough to qualify for the greatest benefits of the pension system and become “pension millionaires.”

*Benefit calculations are based on the Alexandria Public Schools’ salary schedule for teachers serving 205-day calendar years. Does not include cost-of-living adjustments. Virginia grants cost-of-living adjustments (COLA), matching the first 2 percent increase in the Consumer Price Index for all Urban Consumers and half of any additional increase up to 2 percent, for a maximum COLA of 3 percent.

Andrew Biggs has an interesting new report for the American Enterprise Institute investigating the generosity of public-sector pension plans.* He finds that, for the average full-career state worker, traditional defined benefit plans are working quite well and many of these workers are de facto “pension millionaires” because of the amount of money they can expect to receive in retirement.

How does this square with reports from some states that the average pension is quite modest? As we’ve written about for teachers in Illinois and California, the “average” pension is skewed by many employees who qualify for only a very small pension. It’s not accurate to use the statistical average as any indicator of actual payments. To find the typical pension payment, it would be better to look at the statistical median (the midpoint) or even the mode (the most common) amount.

Biggs looks at something different, the payment provided to full-career state government workers. (The piece has an important section reminding readers that the group of workers remaining in the pension plan for a full career is a small group. They are the relative winners in the pension lottery, and all other participants subsidize their pension benefit.) Biggs uses state pension data to look at how well these long-term workers fare under the current system.

There are variations across states, but overall they fare pretty well. In the average state, a full-career state employee receives an annual pension of $36,131. Biggs also converts these figures to total pension wealth and finds that the average full-career state worker can expect to receive $768,940 in pension payments over the course of their retirement.

The numbers are startling, but “generosity” is inherently a judgment call. Another way to look at this question is how much the average pension payment can replace the employee’s pre-retirement earnings. Because retirees tend to face lower expenses than workers, most experts suggest they aim for a 70 percent “replacement rate” in retirement.

The average full-career state employee pension, combined with Social Security where it’s offered, provides an 87 percent replacement rate, meaning these workers can expect to receive $.87 in retirement for every $1 they were earning pre-retirement. This is above the margin commonly suggested by retirement experts and suggests that these workers are “over-saving” for retirement. They’re taking too little of their compensation in the form of present-day salaries and too much in the form of deferred retirement savings. This could be especially problematic for workers with children or those who face other spending constraints, because they’re forced to follow the pension plans’ mandatory contribution rates even if they might prefer more upfront cash and less in savings.

These are two different problems with two different solutions. If the public and policymakers think $36,000 a year in pension payments are too generous, they might support policies that cut retirement benefits and overall compensation for government workers. They may end up with a less generous defined benefit pension plan with all of the same structural problems that exist today. Cutting compensation is also not not likely to help governments attract high-quality workers. That does not mean pensions don't need to change. Pensions may not be overly generous but they still limit individual choice, fail to provide a secure retirement savings path to all workers, and improperly balance upfront and deferred compensation. But those problems demand different solutions than cutting compensation. For example, policymakers seeking to improve the quality of their workforce would support restructuring retirement benefits while simultaneously raising base salaries. The two positions start in the same place but end very differently. The former would cut overall compensation for government workers, while the latter could be cost-neutral. The end goal should be better, not worse, compensation.

*To be clear, Biggs focuses only on state government employees, not teachers, although many of the findings would be similar.

Taxonomy: