In June of 2012, a majority of San Jose, CA voters approved changes to pension and retiree health care plans for city workers. In late December 2013 a judge ruled that certain components of the city’s reforms changing future pension benefits for current employees violated the state’s constitution. The ruling relied on a legal precedent known as the “California Rule,” which protects the right of workers, from their first day on the job, to accrue future benefits. For more background, see here or here.

Mayor Chuck Reed led the local initiative in San Jose and is now sponsoring a statewide ballot initiative that would change California’s constitution to allow state and city governments to make prospective changes to retiree benefits. The change would protect any benefits that an employee had already accrued, but would no longer guarantee employees the right to accrue the same level of benefits forever into the future.

To better understand the initiative and why he’s sponsoring it, I spoke with Mayor Reed. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Chad Aldeman: First, can you say what drew you to pension reform? Why take it up as a key issue?

Mayor Reed: Well, I took it up as Mayor because, after a decade of cutting services to balance the budget, I thought it was necessary to take on the primary cause of budget shortfalls: skyrocketing costs. The main drivers were retirement benefits (in the aggregate) including pensions and retiree healthcare. And the choice was to continue to cut services or take action. I thought we should take on the most significant factor which was increasing costs for pensions and retiree healthcare.

Aldeman: You’re a lead sponsor of a potential ballot initiative that would allow state and local governments to make prospective changes to pensions. Can you say more about the initiative, how it would work and why you support it?

Reed: The initiative would put language into the California Constitution that does two things: protects the benefits public employees have earned, as they’re earned; and, two, allow elected officials around the state — the cities being the most important to me, but the state of California as well — to negotiate changes to bring down the costs of retirement benefits by making changes to benefits that would be earned in the future under future contracts for future years of service. That allows us to deal with the skyrocketing costs – by dealing with future accruals for future years of work, while protecting what people have already earned.

Aldeman: The initiative would also require state and local governments to prepare detailed funding status reports, which the California Legislative Analyst’s office estimates could cost tens of millions of dollars. Why did you choose to include this provision in the initiative?

Reed: Well, I thought it was important to be honest with the people: the taxpayers who have to make the payments, the employees that have to make the payments, and the retirees that are counting on the systems to have the money and to be there when they retire. We ought to be open and honest about whether or not there are adequate funds.

It’s a reporting requirement, not an action requirement. It doesn’t require people to take any steps to deal with the problem. But it does require them to be honest about it, and to be open and transparent about the size of the problem. Retirement systems that have less than 80 percent of the funds available to pay for the benefits would have to do a report based on the actuarial work that they already do. There would be a public report, a public hearing, a public debate, a public decision, so that people wouldn’t be shocked to find out, for example, that the California teacher’s retirement plan [CalSTRS] is grossly underfunded. I think everybody should know that. Every teacher should know that their retirement funds are grossly underfunded, and they ought to know when they’re going to run out of money. And I don’t think that’s widely known by beneficiaries of the plans or taxpayers. This would be a requirement to get the information out.

Aldeman: The Attorney General recently supplied a title and a short description that would go on the ballot. What’s next? Were you happy with the wording, and are you planning to go forward with it or wait?

Reed: I am not happy with the wording. It is inaccurate and misleading. So we are considering our options. One of those options is to file an action in Superior Court to get the wording corrected. I am conferring with our lawyers and our state coalition to see what action we might take. We haven’t decided that next step.

Aldeman: Can you say more about the wording? What did you not agree with?

Reed: I think when people read the first sentence of the summary, they are likely to conclude that we are proposing to eliminate the vested rights of future work performed. We’re not proposing that. That’s not our intention. We don’t want to do that. In fact, as people perform work, we believe that their benefits ought to be vested as that work is performed. So it’s contrary to what we’re trying to do and certainly contrary to the language of the initiative which is why it is inaccurate.

Aldeman: CalPERS announced recently that its investments grew at a 16.2% rate in 2013. Steve Maviglio, a spokesman for Californians for Retirement Security, said this rate of return “takes the wind out of the sails” of pension reform efforts. How would you respond to those claims?

Reed: Well, it’s good news that they’ve gotten good returns this year. It’s good for everybody. It’s good for beneficiaries, good for the plan sponsors, good for the taxpayers. So that’s excellent news.

Unfortunately, the problem hasn’t gone away with a good year’s return. The unfunded liabilities remain. In California, hundreds of billions of dollars at the state level alone, and then when you factor in the local level, much more than that. Those unfunded liabilities haven’t gone away with one good year’s return and even a couple of good years’ returns are not going to take care of those unfunded liabilities. CalPERS has notified their participating agencies (and there are thousands of them) that they expect a rate increase of 50 percent over the next six or seven years, and that’s creating problems and will create problems for cities and agencies all over the state.

Aldeman: Recently there have been some high-profile cases of cities declaring bankruptcy in part from rising pension costs: Detroit, Californian cities like Vallejo, Stockton, and San Bernardino, as well as cities in Alabama and Rhode Island. Some people point to these instances as bellwethers of what’s to come, while others say they’re extreme examples without larger implications. How broad is the pension problem?

Reed: Well, I think it’s a very broad problem. Bankruptcy is basically a last resort for cities. The mayors I know will do everything they can to avoid bankruptcy. But it is clearly a big enough problem nationally that cities have gone into bankruptcy and they’re not alone in the distress that they’re experiencing. So I expect that there will be more bankruptcies.

But even without a bankruptcy, there are cities that are having great distress over skyrocketing retirement costs crowding out other services. We’ve experienced that here in San Jose. Many other cities are experiencing the same problem.

Short of bankruptcy, you can be in service delivery insolvency, which is when you have enough money to pay your bills, but beyond that, you just can’t provide basic services to your taxpayers and residents. There will be many more cities that are in that situation. But even cities that aren’t extremely distressed have seen cuts in services as these cost increases are crowding out other services. We’ve seen that all over the state of California in cities large and small. And that’s a problem.

What I draw from these bankruptcies are some things that we should all avoid doing. Because typically, like in Detroit, there are many causes. If you look at the recent bankruptcies, you can see that retirement benefits and unfunded liabilities are a huge part of the debt that these cities are incurring. When they get in trouble, they can’t afford to pay their obligations and retirement costs are part of what takes them into bankruptcy. And once you’re in bankruptcy, then we’re seeing that retirement benefits are being cut in bankruptcy, something I want to avoid. I want to make sure that everyone gets paid what they’ve earned. That is why I’m advocating that we take action now, so we can deal with future accruals and not have to be cutting benefits like they’ve done in these bankruptcies.

Aldeman: What message would you have to the governor or other leaders in California? What steps can they take to help cities manage their pension liabilities, pension debts?

Reed: Well, they can support my constitutional amendment. Because in California, under what’s referred to as the “California Rule of Vested Rights”, there are currently a very limited number of things that cities, counties, and the state of California can do to deal with the cost of pension benefits. We need a constitutional amendment to make it clear that – while we’re protecting benefits that have been accrued, that they’re vested and protected – benefits that might be accrued sometime in the future should be negotiable, just like wages in the next contract are negotiable. So, I would ask them to support my constitutional amendment because that allows the state of California to do the things it needs to do to deal with the state’s share of problems as well as local governments having the flexibility to negotiate changes to future contracts.

One more thing that I would ask them to do is to pay what they owe to the California Teachers’ System. The state of California is shorting CalSTRs by about $4.5 billion a year and they should be paying that.

Aldeman: You’re a twice-elected Democratic mayor in a county where 70% of the 2012 presidential vote went to the Democrat. You’re also the lead sponsor of an initiative that would allow cities and the state government to potentially reduce pension payments to government workers like teachers, state employees, and police officers, all groups that are traditional Democratic supporters. What does this say about pensions and the politics of pension reform?

Reed: First, let me just clarify that we’re not trying to reduce pension payments. My proposal would ensure people get paid what they’ve already earned. So the people already retired, we’re not talking about changing their pensions. What we’re trying to do is change the future accruals and things like that.

As you mentioned I’m a Democrat, in a Democratic city, and most of my councilmembers are Democratic. So why did we take on pension reform? Basically, the pain of doing nothing was worse than the pain of taking on the reforms. We have cut services for ten years. We were facing a fiscal disaster. We were facing service delivery insolvency. We laid off police officers, we laid off firefighters, we closed libraries, we closed community centers, and we decided that we couldn’t continue to cut services. We had to deal directly with the problem and that problem required us to take on retirement reform. And that’s why we did it. We were sick and tired of cutting services.

Aldeman: Is there anything else that you would like to say or things that you wish people would know about your initiative?

Reed: People should understand that we’re trying to do two things: one is to make sure that people get paid what they’ve earned, and the second is to make sure that we can provide basic services for our residents and taxpayers. Those two goals are hard to do simultaneously. If we were choosing one or the other, it wouldn’t be that hard. We’re trying to do both and those twin goals make it a very difficult thing to do. But that’s our objective.

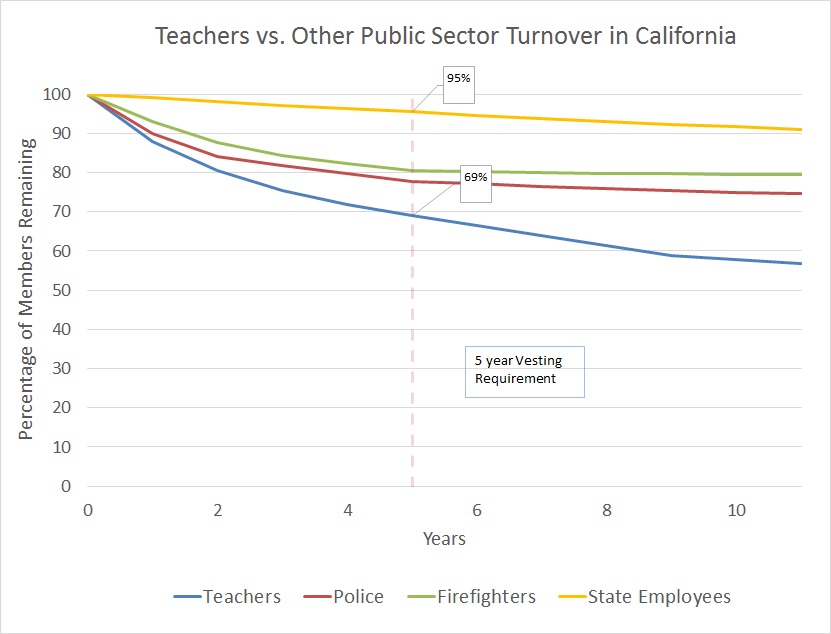

Taxonomy:- Unnecessarily high turnover is a problem in any field. Turnover results in increased costs in lost work during vacancies, recruitment, and retraining, all of which contribute to overall productivity losses and lower quality of service. In the public sector those services are the ones that we all benefit from: police and fire protection, government offices ranging from the Department of Transportation to the Environmental Protection Agency, and in education, public school teachers. How much does turnover affect various public sector occupations? We can use state pension calculations to find out.In the state of California, teachers and other public sector employees are channeled into two different retirement systems. Teachers participate in the California Teachers State Retirement System (CalSTRS). All other state and public agency employees participate in the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS). CalSTRS represents the largest educator-only pension fund in the world and boasts a total of 862,192 members and approximately $191.1 billion in assets. CalPERS totals 1,678,996 members: 30.3 percent are state employees, 30.7 percent are local public agency employees, and 39 percent are non-teaching school employees (this is made up of non-credentialed employees such as janitorial staff, secretaries, attendance monitors, etc.).To compare turnover rates among public sector workers, we compiled data based on the actuarial assumptions found in CalSTRS and CalPERS’ Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports. While the data represent the plan’s assumptions for the future, not the actual rate, the assumptions are based on semi-regular experience studies that look at recent historical trends (for example, CalPERS updated their assumptions in 2010 based on historical data from 1997-2007).We compiled this turnover data for teachers, police officers, firefighters, and individuals employed by the state of California, California State University, or California community colleges who were not involved in law enforcement (labeled as “state employees”). The graph below shows the results.Sources: CA Public Employee’s Retirement System and CA Teachers’ Retirement SystemFor all groups, turnover occurs most during the first few years of service and flattens in the later years. However the drop-off is steepest for teachers (blue) but very low for state employees (yellow), over 90 percent of whom remain even after ten years.Now compare teachers and state employees with the police and firefighters. Where state employees have a less than 5 percent cumulative attrition within the first five years, police and firefighters have more than triple this, with 20 percent or more attrition. Teachers in California have nearly six times the attrition of state workers, with over 30 percent turnover during the first five years.Teachers are often lumped in with other public sector workers, but the turnover rates of the teaching profession places them in a much more volatile position than other state or local government positions. On the national level, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, teachers had nearly twice the annual turnover rate as state and federal government workers.In terms of retirement, these turnover rates also give us a picture of the retiree pool. To even qualify for a minimum pension in California, teachers, police, firefighters, and state employees must serve at least five years. Where 95 percent of all state employees meet the five year vesting requirement, the numbers are steeper for teachers. With a turnover rate of over 30 percent at the five year vesting mark, roughly one-third of California teachers will leave the profession before qualifying for even a minimum pension. Furthermore teachers from California are excluded from Social Security, leaving a substantial group of teachers with neither a state pension nor Social Security.In certain states, teachers are placed in the same retirement system as all other public sector workers. But as the turnover rates suggest, such systems may be treating unequal employee groups equally. While California teachers are channeled into a separate retirement system from other public sector employees, both CalSTRS and CalPERS follow the same structure of a traditional defined benefit pension where benefits are not tied to contributions and are back-loaded toward the end of the employee’s career. Traditional defined benefit pension plans may make more sense for the more stable pool of public sector state office employees, but for teachers, the current system simply doesn’t have the same breadth of coverage when significant portions of teachers will not receive a pension at all. Teachers are a unique labor force whose trends differ from other traditional state and local government workers. States should in turn consider the varying patterns of their labor force so that they can build a retirement system that better fits the demands of its employees.Taxonomy:

Defined benefit pension plans include two key points in time for all members. First, there's a "vesting" requirement, the period of time the employee must work before they qualify for even a minimal pension benefit. Most state pension plans for teachers have either a 5- or 10-year vesting requirement. The second key point in time is when teachers are first eligible to retire and start collecting benefits. If pensions are a tool to boost teacher retention, we should see teachers change their behavior around these two key points in time.

There is ample research showing teachers do know and respond to the financial incentives tied up in their retirement age. Research from Missouri and California has shown that teachers nearing retirement age do time their retirement for when they hit their peak retirement compensation. This acts as a retention incentive for teachers nearing their full retirement age, but it also pushes out some veteran teachers who would have otherwise kept working. This makes sense, because, at that point, every year they keep working is a year they could be retired with nearly the same income. They could work another year for 100 percent of their salary, or they could retire from working, do something else, and still receive a large portion of their salary in the form of a pension.

The full retirement age varies across the states, but it typically falls somewhere between ages 50 and 60 for teachers who have been working 20 or 25 years. Unfortunately, not that many teachers remain in the profession that long. In fact, one recent report found that teachers in 9 of the 10 of the largest school districts had less than a 10 percent chance of remaining employed long enough to receive the maximum pension payout.

What about the majority of teachers that won’t reach these career milestones? Do pensions affect their retention decisions?

Conceptually, a teacher facing a 10-year vesting requirement likely does not say to herself, in her 3rd year of teaching, “well, I don’t like teaching here very much, but if I just stick this out for seven more years, at least I’ll qualify for a minimal pension!” The pension-as-retention-incentive argument looks even stranger when you consider it from the employer’s perspective. States and districts have been lengthening their vesting requirements in the last few years because it saves them money. It takes a giant rhetorical leap to argue that offering cheaper, worse benefits to teachers through longer vesting requirements is an incentive for them to stay in the profession longer. (This same logic applies to those who argue that pensions are a recruitment incentive.)

Empirically, pensions appear to have no effect on early- or mid-career teachers. Take Washington, DC as an example. Below I’ve copied and pasted their withdrawal assumptions based on a teacher’s age and years of experience. The table comes from the District of Columbia Retirement Board's (DCRB) 2012 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report. With a 5-year vesting requirement, we should expect to see withdrawal rates slow down in years three and four as teachers closed in on vesting. Then, we’d see a spike of departures right at the 5-year mark. But that’s not what happens. DC doesn’t even have a separate calculation for teachers with five years of experience. It assumes a teacher with four years of experience is no more or less likely to leave than someone with five years, and someone with five years is no more or less likely to leave as someone with six years of experience. DCRB assumes vesting has no effect on teacher withdrawal rates whatsoever. Across all ages and years of experience, it assumes the withdrawal rate starts high and declines gradually over time.

Lest you think I’m cherry-picking numbers or the D.C. pension assumptions aren’t applicable elsewhere, take a look at New York City’s actual teacher attrition rate. Here are the percentage point declines in New York City teachers who began teaching in 2001-2, by year: 18 points, 16, 5, 5, 4, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1.

These teachers were eligible to vest into their pension plan after five years, but there’s no noticeable change around year five. As in D.C., a lot of New York City teachers leave in their first few years and departures fall gradually from there. (You can see this same data graphically here.) There’s no evidence of teachers knowing about or reacting to the 5-year vesting period. Even when looking at multiple cohorts of entering teachers, there’s no noticeable jump around the 5-year vesting requirement (See Table 3.17 here). As in D.C., the Teachers’ Retirement System of the City of New York does not estimate any change in teacher behavior based on the vesting requirement.

In the next few months, Bellwether will be releasing a paper looking at this sort of data for every state. Having looked at each state’s assumptions for teacher turnover assumptions, I can tell you that the pattern from D.C. and New York repeats itself all over the country. According to their own data, state pension plans are simply not a retention incentive for the vast majority of teachers.

The Louisiana Budget Project is out with a short report attempting to show the economic benefit of pensions. The figures are big, but the logical leaps are bigger:

Altogether, Louisiana's 13 pension systems pay out more than $3 billion in benefits to 150,000 retirees and their families every year--an amount equivalent to 1.7 percent of all personal income in the state. These dollars don't just sit in savings accounts, but are spent and pumped back into the local economies, where they pack a big economic impact, supporting everything from car dealers and restaurants to grocers and hospitals.

The Louisiana Budget Project uses the total size of the payments as justification that pensions shouldn't be reformed, but size shouldn't be the end-all argument. We would never apply that same logic to other industries with similar economic contributions. As the report documents, pensions contribute about the same amount to the Louisiana economy as salaries in the chemical manufacturing and restaurant and food industries. Would it be acceptable to argue that we shouldn't regulate chemical manufacturers because they're so large? What about the working conditions or cleanliness at restaurants? Economic benefits are important to consider, but they're not a sufficient reason to halt policy discussions that weigh the trade-offs comparing the status quo with other alternatives.

Most importantly, touting the size of pension systems as a reason not to change is oblivious to other alternatives. Louisiana public-sector workers generally don't receive Social Security, but that was a choice the state made long ago. If they had been in Social Security, the Louisiana Budget Project could have created a nearly identical analysis showing how much Social Security contributed to the local economy. This wouldn't show anything about the effectiveness of the program or other alternatives, but it would be a large number!

Louisiana is not alone in making these types of nonsense economic arguments. See here, here, or here. But we need to get past these discussions of size and start talking about the most effective ways to ensure retirement security for all public sector workers.

Taxonomy:Every state except Vermont has a balanced budget amendment requiring state legislators to spend no more money than they bring in as revenue. Yet, states have wracked up large unfunded liabilities for their pension and retiree health plans. How can both of these things be true at the same time? Watchdog.org digs into a new State Budget Solutions report and explains how this works.

Taxonomy:This post was written by Bellwether Pensions Analyst Leslie Kan.

Like city and state governments, the federal government is facing rising pension costs and is dealing with them in similarly unproductive ways. Congress’ recent Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 included controversial provisions that reduced the pension benefits for two groups: federal employees and military retirees.

Specifically, the two groups affected are new federal employees hired on or after January 1, 2014 and military personnel retiring before the age 62. Contribution rates remain the same for federal employees hired before this date, but new federal employees must now contribute 4.4 percent of their salary toward their retirement, a 1.3 percentage point increase. Cuts to military pensions, on the other hand, come from a reduction in cost-of-living adjustments or COLA. A military personnel who retires before the age of 62 will have a 1 percentage point reduction from their COLA until they reach the age of 62, whereupon the normal rates apply. The plan will not affect high ranking military officials. The pension cuts contribute to $12 billion in budget savings, $6 billion coming from retirement reductions for new federal workers and $6 billion for military personnel.

To put this into real world perspective, let’s take for example a federal employee newly hired in 2014 and salaried as a GS-09 Step 1. As a GS-09 Step 1 she makes $51,630 annually. Where her FERS (Federal Employee Retirement System) Annuity would have been 3.1 percent of her salary or $1600.53 if she were hired in 2013, under the new Budget Act, she now faces a FERS Annuity payment of $2271.72. Her costs have risen by $671.19. The jump is even steeper when we compare this to the rates for employees hired between 1984 and 2012 when the rate was 0.8%. Her annuity during the 1984 to 2012 time frame would have been $413.04. Through this lens, she is paying almost $1,900 more than if she were hired just a few years earlier.

To put the changes in military retirement benefits in context, take an example that has been well-circulated by the media: a woman enlists in the army beginning at the legal age of 18 and remains in service until she turns 38 years old. At 38 years, she has now reached the 20 year minimum to qualify for a military pension. However, she is also under the age of 62 years and therefore will receive the one percentage point COLA penalty under the new Budget Act. According to House Budget Committee staff, our military woman’s total retirement wealth would be reduced from $1.734 million to $1.626 million under the Budget Act.

So how does this relate to teacher pensions? One thing to consider are some of the overarching similarities in pension structures, particularly within the military. Certainly the military and teaching are very different professions and their retirement systems are not wholly analogous. But it is interesting to note that in both cases pension accrual is based almost completely around service time, rather than the nature or type of service performed (notwithstanding of the exemption for high ranking military officials, but even here time constitutes a main variable). The military is also subject to high turnover rates and very few employees qualify for the full retirement benefit. According to the Pentagon, only 17 percent of the military serve 20 years or more and hence qualify for a pension. The remaining 83 percent leave the service without the retirement security of a full pension. As in teaching, the majority of the military labor force will not be able to rely on the pension system providing them with an adequate retirement.

In terms of Congress’ decision: in one sense it may have been a gesture, however indirect, towards some much needed reform in public sector pensions. On the other hand, it may just have been an effort to make a deal by tweaking bloat in the system. As NCTQ and the Fordham Institute have written about, several states have put in place similar adjustments in COLA reductions or increases in retirement age for teacher pensions. However, these small tweaks and adjustments preserve the existing system’s basic structure while doing nothing to address larger human capital problems.

*Examples as calculated from the U.S. Office of Personnel and the House Budget Committee.

Taxonomy: