It was May of 2012 and, like many other states, Kansas’ state-based teacher retirement plan (part of the Kansas Public Employee Retirement System, or KPERS) was in trouble. Facing a looming $8.3 billion unfunded pension liability, the state’s financial situation looked grim. As a response, legislators voted in a new retirement option, called a cash balance plan, for teachers hired on or after January 1, 2015. Below, we take a look at what the plan offers, and how it's worked out a year and a half later. Here's the breakdown:

What is a cash balance plan?

A cash balance plan is a hybrid, combining aspects of a defined contribution, 401(k)-style retirement plan within the format of a defined benefit plan, like most pensions. Individual employee retirement balances are stated in terms of an account balance, rather than a formula, but the employer takes responsibility for investing the assets and guarantees at least a minimal level of return on those investments. Kansas isn't alone in adopting this format. We've covered a similar cash balance plan in California, which offered most workers a better deal than the state's existing pension plan, and Nebraska's version has been lauded by both Pew and The New York Times.

How does it work?

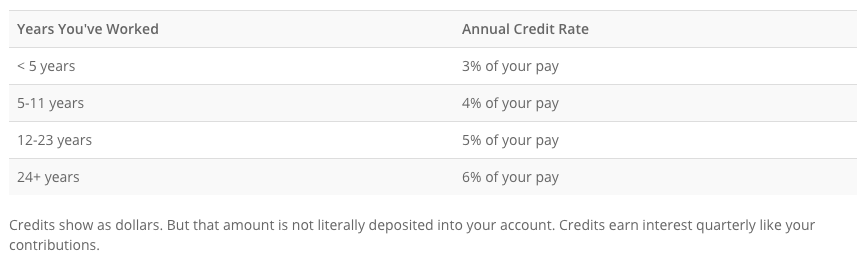

In Kansas, enrolled employees automatically contribute six percent of their salaries to the plan, and the state then invests the money and guarantees at least 4 percent annual interest. This guaranteed interest rate sets the cash balance plan apart from retirement plans like 401ks where workers are left on their own to invest and are subject to the ups and downs of investing in the stock market. In addition, teachers also earn retirement credits, based on a percentage of salary and years of service. These credits are earned quarterly, and the credit rate increases the longer a teacher works. The table below, created by KPERS, breaks this down further.

While these retirement credits, like traditional pensions, are available only at retirement, employees can withdraw their own contributions plus that promised interest should they leave employment.

Why is this particularly relevant in Kansas?

Sweeping income tax cuts were the cornerstone of Governor Sam Brownback’s re-election campaign, and his financial experiment has left the state’s budget gutted. While the vast majority of states would benefit from public pension reform, Kansas’ need is all the more pronounced. The cash balance hybrid plan is a step in the right direction, but more work needs to be done.

Where are they now?

Well, the cash balance plan didn't solve everything. This time last year, lawmakers voted to shore up the pension fund using a $1 billion bond; the bond has a roughly 4.7 percent interest rate, while the state is assuming they can invest that money and earn 8 percent interest. But in fact, KPERS officials reported that the fund earned just 0.2 percent during 2015 — a far cry from the 8 percent rate the state assumed. But that's not all. Last fiscal year, lawmakers also delayed a $100 million quarterly KPERS payment. They now have until June 30, 2018 to make the payment, plus the same 8 percent interest on that money. State legislators from both parties have expressed skepticism that even this delayed deadline will be met.

The traditional pension plans (KPERS 1 and 2), as well as the newly created cash balance plan (KPERS 3), are all paid from the same budget. The progress made in adopting a cash balance plan is commendable, but, unlike a 401(k) plan, it allows the state to continue to delay contributions. While it's unlikely, Kansas would run into trouble if enough KPERS 3 employees decided to leave the profession or move out of state, demanding their contributions plus the promised interest in the process. Kansas is making progress, and moving to a new pension plan might very well be good for new workers. At the same time, it hasn't solved all of the state's budget woes.