Teachers in Denver, Colorado are on the brink of going out on strike. Given last year's statewide demonstrations in Colorado, West Virginia, Arizona, and Kentucky, not to mention the recent teacher strike in Los Angeles, it might be tempting to think of Denver as just one more data point in a larger national trend of teacher activism. But Denver is different for a few reasons.

First, unlike the rest of the contry, teacher salaries in Denver have been going up. Denver teacher salaries have risen 4.1 percent a year over the last five years, which is a faster growth rate than its overall per pupil spending (see data on page 27 here). The district is now proposing a further 10 percent raise, and the union is requesting a raise of 12.5 percent. Those are much larger numbers than in Los Angeles, for example, where the union ultimately agreed to a 6 percent raise phased in over two years.

Second, as Rick Hess notes in an excellent piece for Forbes, the Denver debate is largely over a pay-for-performance program called ProComp that began in 2005. The district and union are not all that far apart on total spending, but the disagreement is largely about how that money is allocated and whether it should go toward base pay or incentives.

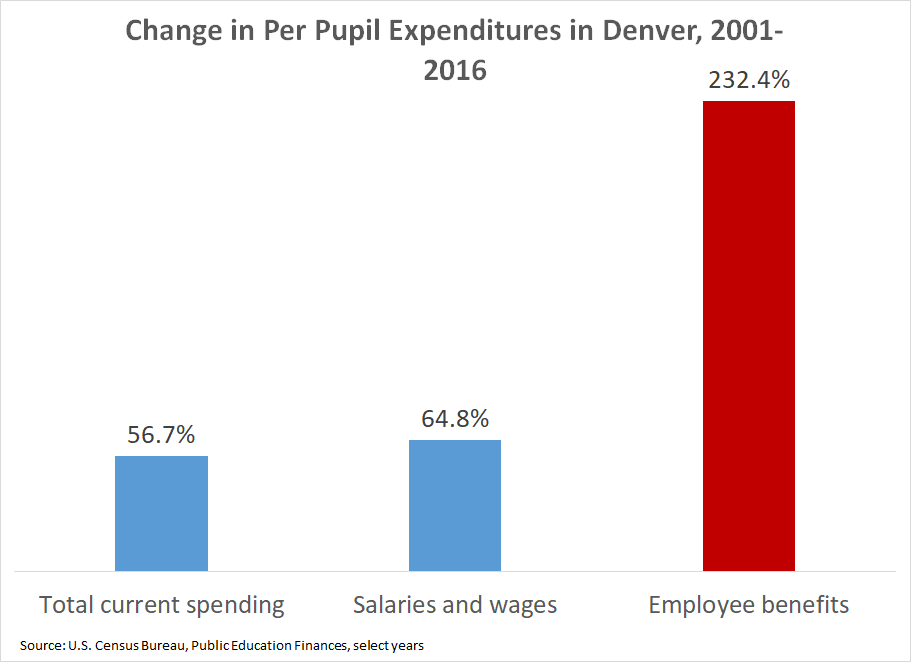

Still, if I were a Denver teacher, I would be upset about the district's inability to control spiraling benefit costs. While Denver has seen revenue increases and has been able to translate a good portion of that into higher salaries, the increases to base salary pale in comparison to Denver's spending on benefits. To show what this looks like, I created the graph below using data from the U.S. Census Bureau. As the graph shows, from 2001 to 2016 Denver increased current spending per pupil by 57 percent, and it increased spending on salaries and wages by 65 percent, but its spending on employee benefits soared by 232 percent. That is, Denver's spending on employee benefits rose about four times faster than its spending on salaries and wages.

Part of this is due to changes in health care costs, but the state pension plan is also a big factor. Mandatory contribution rates to the Colorado teacher pension plan doubled between 2001 and 2016, and they've continued to rise since then.

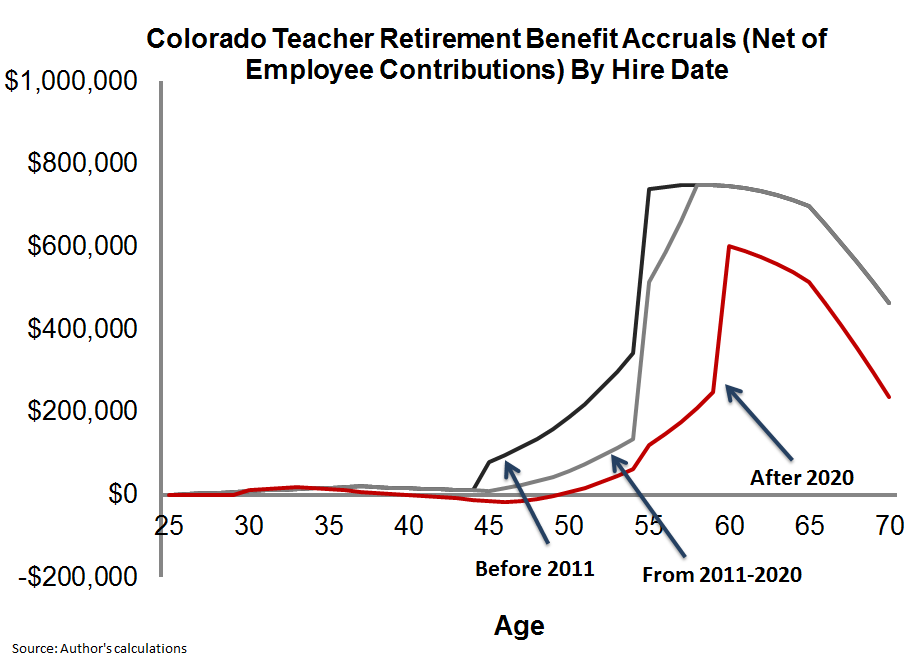

In fact, in legislation passed late last spring, Colorado cut benefits for new hires and further increased employee and employer contribution rates. As I showed at the time, the net result is a dramatic decline in the value of Colorado teacher retirement benefits. The graph below shows the value of a teacher's pension under the Public Employees Retirement Association (Colorado PERA) depending on hire date. Workers hired before 2011 were placed in a back-loaded plan that required them to stay 20 or 30 years before qualifying for a decent benefit (represented by the solid black line). But the state offers worse benefits to those hired between 2011 and 2020 (the gray line), and it will offer even worse benefits to teachers hired after 2020 (the red line).

To be clear, Denver as a school district has no control over the statewide pension plan. Those rules are set by the legislature and apply to all educators across the state. But Denver teachers are getting a particularly raw deal. Denver has a relatively mobile teacher population, meaning fewer of its teachers will stick around to reach the back-end peaks built into the state pension plan formulas. And given its fast-growing population, Denver will have a disproportionately large share of teachers hired into the new, worse benefit tiers.

These benefit issues may not get the same attention as the fight over base salaries, but Denver residents should be concerned about how their school district's budget is being spent and how little control they have over this important part of it.

Taxonomy: