In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were fears of a massive wave of teacher retirements. After all, older people were and remain more susceptible to the virus, and it seemed reasonable to expect that older teachers might have experienced a rougher transition to remote learning.

It didn’t play out that way. In fall 2020, most schools across the country stayed closed, which took the immediate health risks off the table. When Alex Spurrier and I looked at the retirement numbers available that fall, we found they were mostly down.

Speculation, combined with bad data, continued to perpetuate the teacher retirement narrative nationally. For example, in February 2021, the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) wrote a blog post noting that midyear retirements were up by 26% over the same period the year before. Media outlets warned that, if trends continued, teacher retirements could hit “record-breaking heights.”

Did the trends hold?

They did not. Pension data are slow, but when it eventually released its official, full-year data, CalSTRS reported that the number of retirements for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2021, was nearly identical to the number for 2018 (see Table 6 of its actuarial report).

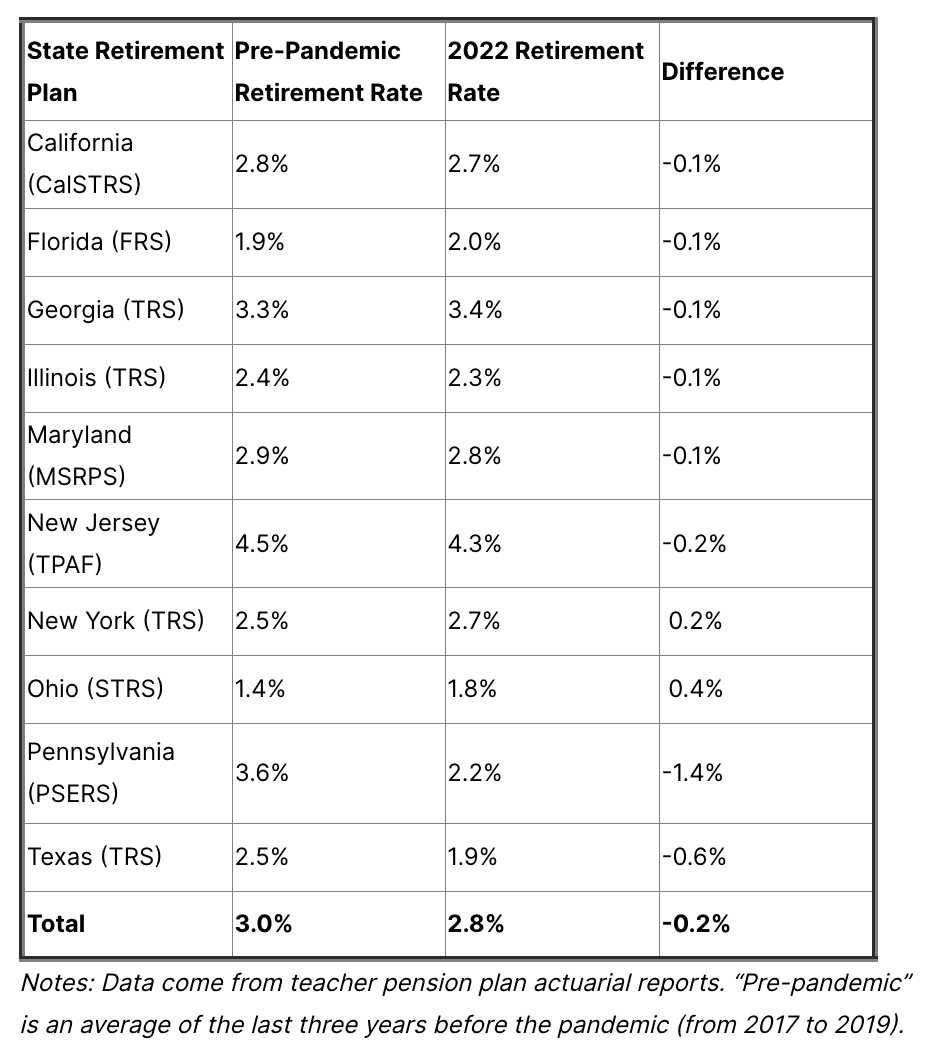

In fact, retirement rates across the largest teacher pension plans in the country have remained relatively stable over the course of the pandemic. Figure 1 below shows state trends for the five largest pension plans covering teachers. Although there is some evidence of a dip in 2020 followed by an uptick in 2021, there’s no clear pattern across all five. There’s certainly nothing pointing to a massive surge of retirements.

Figure 1: There Has Been No Surge in Retirements From the Largest “Teacher” Pension Plans

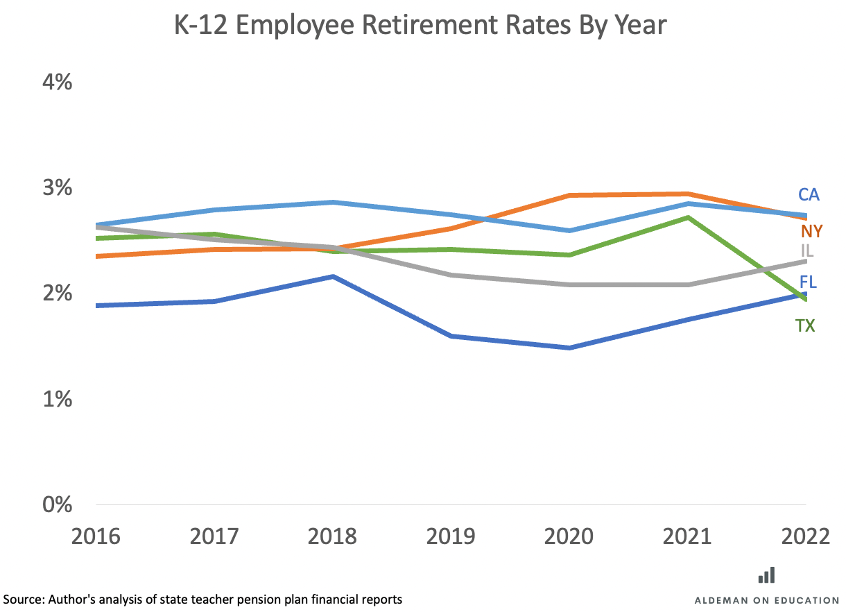

Table 1 takes this a step further, comparing the latest retirement rates with pre-pandemic averages for the 10 largest pension plans serving teachers. Six had a lower retirement rate in 2022 than they did in the three years leading up to the pandemic — and the total retirement rate across all 10 plans is down, not up.

Notes: Data come from teacher pension plan actuarial reports. “Pre-pandemic” is an average of the last three years before the pandemic (from 2017 to 2019).

These data illustrate why it’s important to look at retirement rates rather than raw numbers. As COVID-19 should have taught us, raw numbers might sound scarier, but denominators matter because they put things in context. CalSTRS, for example, had 12,785 new retirees in 2021. But that number doesn’t mean much without knowing that CalSTRS had 448,419 active members at the time. Dividing the number of retirees by the number of active members works out to a retirement rate of 2.9%.

Putting the Retirement Rates in Context

What to make of the generally flat trend in teacher retirements at the same time reporting shows teacher turnover rates rose last year in a number of states?

First, it’s hard to pin down the exact retirement numbers for classroom teachers versus other types of education workers. For example, CalSTRS is officially the “teacher” retirement system of California, but it also includes other types of education employees. That’s true in other states, too: In Florida, for example, teachers are in the same retirement plan as other non-education state and local government employees, and the state pension plan does not report disaggregated results by role.

Turnover can also vary across many dimensions. For example, some states may be experiencing increases in turnover among early-career teachers even as turnover among retirement-age teachers holds steady — a question worth exploring. And at least one state, Arkansas, has seen a statistically significant 7% increase in turnover among teachers age 55 or older. But even if other states saw similar increases among older workers, that level of change may not be big enough to meaningfully affect the overall retirement numbers since retirement-eligible veterans make up a relatively small share of the total teacher workforce.

Why Are Teacher Retirement Rates So Stable?

About 90% of public school teachers are enrolled in defined-benefit pension plans, with guaranteed retirement benefits based on the worker’s years of experience and age. These plans offer predictable, assured benefit payments regardless of external factors. In addition, about two-thirds of public school teachers serve in states or districts that provide health care benefits to eligible retirees. The combination of retirement benefits plus health insurance means that veteran educators are in a relatively stable position financially.

Research has found that these structural factors make a difference. Veteran teachers are aware of their pension benefits and time their retirements accordingly, even if they no longer enjoy teaching. Because of the way the benefit formulas are structured, pensions can also push out veterans who might otherwise prefer to keep teaching.

Regardless of how highly you value stability over these other factors, the available evidence suggests that teacher retirements have been proceeding normally, even amid a pandemic.