There are five things all Texas teachers should know about their retirement benefits:

- The Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) of Texas is back-loaded, and it leaves the majority of its teachers without adequate retirement benefits.

- The TRS plan is one of the stingiest in the country. On average, Texas teachers receive less money toward retirement than many of their peers in the private sector.

- TRS benefits are getting worse. Due to rising costs, state legislators have slowly reduced benefits provided to new teachers, and teachers who enter Texas schools today are getting a much worse deal than their predecessors.

- Texas lets each individual school district decide whether they want to enroll their teachers in Social Security, creating a patchwork of coverage that is not good for teachers or employers.

- Texas has better options for public servants. In Texas, municipal and county workers are covered by retirement plans which do a better job of providing adequate retirement benefits to all workers.

Each of these points deserves its own section, so I’ll break them down one by one.

1. The TRS system is back-loaded, and it leaves the majority of its teachers without adequate retirement benefits.

The Texas TRS plan is a fairly typical teacher pension plan. As a defined benefit plan, it offers workers a retirement benefit that’s equal to 2.3 percent multiplied by their years of service and their final average salary. As an example, if a teacher taught in Texas public schools for 15 years, and her salary averaged $60,000 over her last five years of teaching, she’d be eligible for annual benefits worth $20,700. The math looks like this:

Annual Pension = 2.3 percent * Years of Service * Final Average Salary

Annual Pension = 2.3 percent * 15 years * $60,000

Annual Pension = $20,700

In Texas, teachers must serve at least five years before qualifying for a pension (this is called the “vesting” period). The state also sets rules on when teachers can begin collecting their pension. For teachers hired today, they can begin collecting a pension check at age 65 if they had at least five years of service, or age 62 if they had more than 18 years of service. (Teachers may also begin collecting retirement benefits at younger ages, but those benefits are reduced for every year early they are claimed.)

This may sound fairly simple, but it’s complicated by the fact that the “Final Average Salary” number is calculated based on the years in which it was earned. That is, if our hypothetical teacher began her career at age 25 and served 15 years, her pension would be based on her salary at age 40. But, critically, she wouldn’t be able to collect her pension until age 65. By that time, inflation would have worn away the value of her pension significantly.

This rule has the effect of limiting how much early- and mid-career workers earn in retirement benefits, and it makes later-career earnings especially important. This system also has the effect of leaving many short- and medium-term workers with meager retirement benefits. In fact, these teachers would often be better off withdrawing their own contributions, with minimal interest, rather than waiting to collect a pension. (Individual teachers should consult with TRS or a financial advisor to find out what's best for them.)

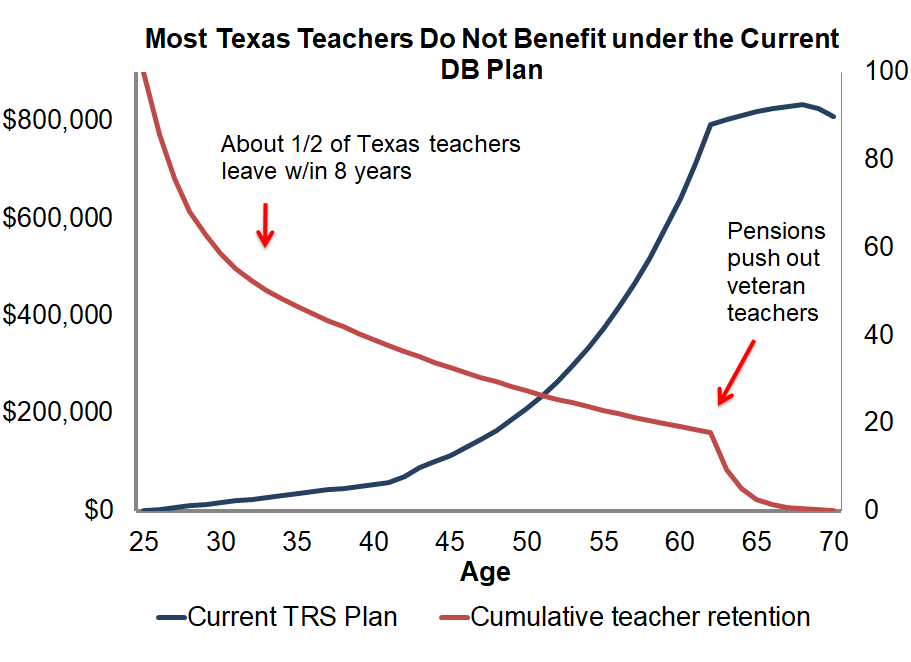

This situation creates a mismatch between Texas’ retirement benefits and the behaviors of its teachers. The graph below shows this visually. The blue line represents how retirement benefits accumulate under the TRS plan for someone who begins teaching in Texas at age 25. As the graph shows, benefits grow slowly for the first 20 or 25 years, and they only begin growing faster as teachers close in on the normal retirement age.

This is not an insignificant problem, because most teachers are gone well before those increases kick in. In the graph below, the red line shows the cumulative teacher retention rate in Texas, based on TRS’ own observations about employee behavior. The state estimates that about half of all new teachers will serve less than eight years, and two-thirds will serve less than 20 years. These teachers will need to find other ways to achieve a secure retirement beyond the TRS system.

In sum, the TRS plan offers adequate benefits only to long-serving veteran teachers. As I’ll show in the last section, there are other models within Texas that could do a better job of protecting all teachers. But first, it’s important to understand the other ways the current TRS system is failing Texas teachers.

2. The TRS plan is one of the stingiest in the country.

Most people hear the word “pension” and assume it must be good for workers. But that’s not always true, and Texas legislators have created a pension plan that is actually quite stingy, from an employer’s perspective. Texas teachers are required to personally contribute 7.7 percent of their salary, but their employers are only contributing about 2.4 percent of salary toward teacher retirement benefits (in actuarial terms, this is called the plan's "normal cost"). That’s less than a typical 401k in the private sector, where employers routinely chip in a 3, 4, or 5 percent match, and it's less than teacher retirement plans in other states.

There are two reasons the numbers above may not match with the public’s perception of the TRS pension plan. One is that the 2.4 percent normal cost represents an average across the entire plan. Some long-serving Texas educators will eventually qualify for pensions that are worth far more than that, while most workers will receive far less. The TRS system includes a number of cross-subsidies, and it works especially well for workers, like principals and district superintendents, who earn higher salaries and have more longevity than classroom teachers, aides, or other school support staff.

The second reason the TRS plan might seem more generous than it is is because Texas employers are contributing another 5.34 percent of teacher salaries to pay off unfunded liabilities (which actuaries refer to as the "amortization cost"). In total, Texas school districts are paying the same amount as employees, but much of the employer cost is going to pay down debt, not for actual employee benefits. This is not an insignificant sum, and it creates a disconnect between the amount employers are paying and the benefits that individual teachers and retirees receive. Worse, these unfunded liabilities have forced the state to cut benefits over time, such that new teachers starting out today are getting an even worse deal than their predecessors.

3. TRS benefits are getting worse.

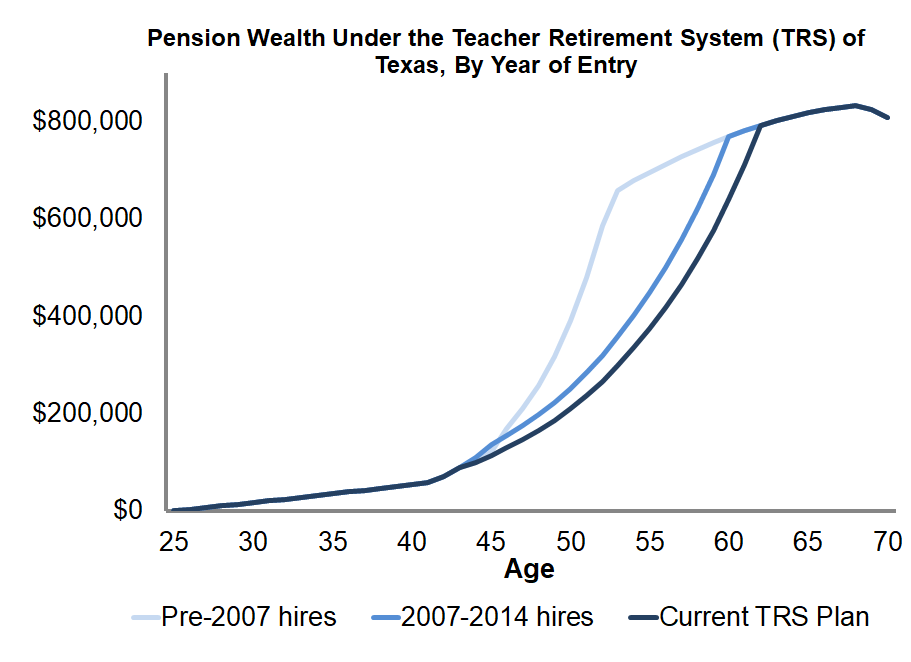

Like a number of other states, Texas has been forced to reduce benefits offered to new entrants in recent years. Texas has chosen to do this primarily by changing the normal retirement age, the point at which teachers are first eligible to start collecting unreduced retirement benefits. All workers are eligible to retire at age 65 with five years of service, but workers hired prior to 2007 could also retire at any age once the sum of their age and years of service passed 80 (commonly referred to as “the rule of 80”). Teachers hired between 2007 and 2014 had slightly less generous rules in that that the rule of 80 only applied to those age 60 or older. Texas again made changes for teachers hired after 2014. Now, teachers must wait until age 62 before qualifying for rule of 80 benefits.

These changes have eroded TRS benefits and made them even more back-loaded. Like the first graph above, the graph below shows how retirement benefits accumulate for a teacher who enters her Texas service at age 25, but this time it shows how benefits accumulate based on the year she began working in Texas schools. As the graph shows, the shifts in the normal retirement age have dramatically changed how teacher retirement benefits accumulate. The darkest blue line represents the current TRS plan, compared to the lighter-colored lines, which represent the benefits offered to teachers hired in earlier years. As the graph shows, teachers hired prior to 2007 had much more generous benefits than those hired more recently.

These changes have effectively made the TRS plan even more back-loaded, meaning fewer and fewer teachers have access to adequate retirement benefits. That’s not a good situation, and it puts more and more teachers at risk of an insecure retirement. This is particularly problematic due to the fact that most Texas teachers lack Social Security benefits.

4. Texas lets each individual school district decide whether they want to enroll their teachers in Social Security.

Due to a historical quirk, Texas lets each school district decide whether they want to offer Social Security to their employees. 17 districts, including Austin and San Antonio, cover all their workers, and another 31 offer some employees coverage. Some regional service centers do as well, as do many Texas universities and community colleges. But that leaves some 1,200 Texas school districts that do not provide Social Security benefits to their workers.

This messy hodgepodge is not good for workers or employers. From a worker’s perspective, they lose out on the nationally portable, progressive benefit structure that Social Security provides. That sort of protection is especially important given the back-loaded nature of the state-run TRS plan. Teachers may also not know at the time of being hired that their employer doesn’t offer Social Security benefits. They may take Social Security coverage for granted, and only find out later that they weren’t paying in and thus won’t receive benefits for those lost years.

Employers bear the Social Security burden in other ways. Social Security coverage might be good for workers, but many people under-estimate its true value. An employer like San Antonio that enrolls teachers in Social Security might be doing right by its workers, but it might also be at a competitive disadvantage in attracting and retaining talent if workers don’t fully appreciate Social Security’s value.

Ideally all teachers would have access to Social Security benefits, but Texas’ split Social Security coverage, and its back-loaded TRS plan, leaves Texas workers in a particularly precarious situation.

5. Texas should look within the state for better retirement options for teachers.

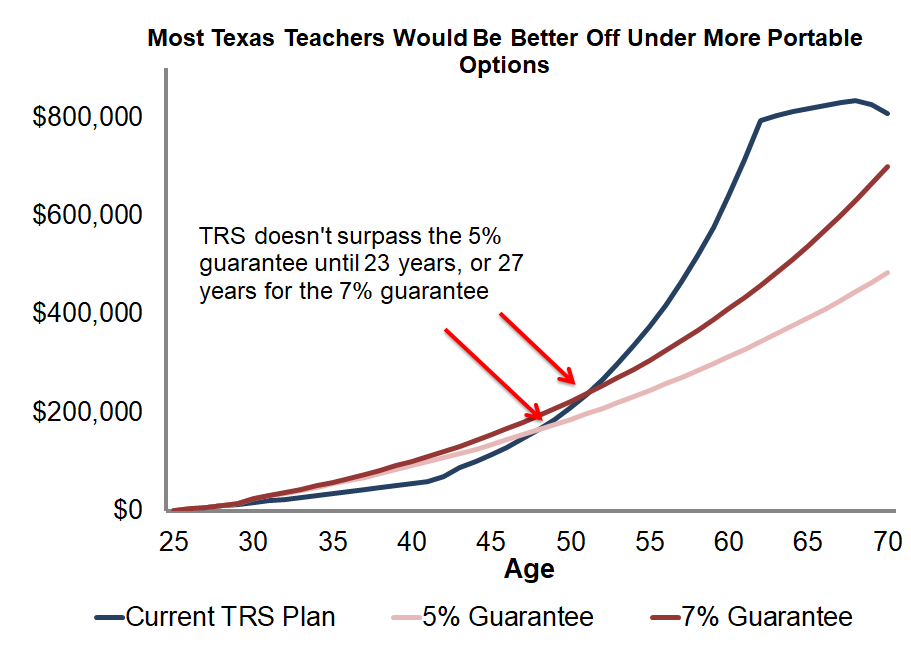

Luckily, Texas already has two alternative models in place that balance the retirement security of workers with financial stability for employers. These plans already serve hundreds of thousands of public-sector workers in Texas, and they could be adapted for school districts and teachers. Both plans are legally considered to be defined benefit plans, but rather than using formulas based on years of service, they guarantee workers a certain rate of return.

Those two plans, the Texas Municipal Retirement System (TMRS) and the Texas County & District Retirement System (TCDRS), are technically called defined benefit cash balance plans. They collectively serve about 350,000 city and county employees, including nurses, mechanics, road crew workers, sheriffs, attorneys, office workers, jailers and judges. Both plans are operated statewide, and they allow participating cities to select an employee contribution rate, an employer match, and a vesting period.

In these types of guaranteed plans, the contributions go into an account in the worker's name. The plan invests the money and guarantees a rate of return, at least 5 percent under TMRS and 7 percent under TCDRS. This provides a more portable benefit with a steadier accumulation of assets than the TRS pension plan. Like TRS, both of these plans help employees when they’re ready to retire. When employees become eligible to retire, the money in their account is annuitized into regular monthly paychecks just like a pension. These paychecks allow for sustained monthly income, mirroring the benefits and stability of a traditional pension plan without the back-loaded accumulation under the current TRS pension plan.

The graph below compares the TRS plan offered to new hires (the same dark blue as in the earlier graphs) against cost-neutral guaranteed plans like the ones currently operated by TMRS (a 5 percent guarantee, represented in pink) and TCDRS (a 7 percent guarantee, represented by the red line). For comparison’s sake, each plan is based on the assumption of a female teacher who begins her career at age 25. Due to the five-year vesting requirement assumed under all three plans, they look nearly identical for the first four years, but the guaranteed plans start looking better once the teacher vests and qualifies for the employer contributions. Because the TRS pension plan bases its formula on final average salaries that are frozen in time, it delivers benefits in a more back-loaded fashion. From a worker’s perspective, they would need to work 23 consecutive years before the TRS plan would be better than a simple 5 percent guarantee, or 27 consecutive years before the TRS benefits would exceed the 7 percent guarantee option. Although these “crossover” points would be shorter for teachers who begin their service at older ages, the majority of teachers would still be better off in the guaranteed rate plans due to high early-career turnover rates.

The plans modeled here assume contributions are identical to the current TRS plan. Enrolling future teachers into one of these plans would not make the current TRS unfunded liability go away, but the guaranteed plans would help the state cap its debt costs at its current levels.

In summary, Texas teachers currently lack secure, portable retirement benefits. Without action, the next generation of teachers are likely to have an even more precarious retirement situation. Luckily, Texas policymakers have good models to build on that already exist within the state. Adapting one of those models to the teacher workforce could help improve the state’s finances and ensure that all teachers are building sufficient retirement assets, no matter how long they work in Texas public schools.