As soon as state legislators begin to seriously ponder teacher pension reform, the specter of West Virginia is raised. Defenders of traditional pensions argue that the Mountain State’s switch to a defined contribution (DC), 401(k)-style plan and its subsequent return back to a pension plan offers definitive proof that reform cannot work.

But that story is vastly oversimplified.

The reality is that both plans are poorly designed and fail to provide a high-quality benefit to a majority of teachers, and that any structure, even one expected to better meet teachers’ retirement needs, can fail if not carefully structured.

In a new report, “Teacher Pension Reform: Lessons and Warnings From West Virginia,” I analyzed all of the state’s teacher retirement plans and modeled wealth accumulation under each of them. We found that both the pension system and the DC plan have design flaws, such as lengthy vesting periods, which severely limit the ability of either retirement plan to provide teachers with sufficient benefits.

The lesson of West Virginia’s attempt to reform its teacher retirement system is not that reform is unachievable and unnecessary. Rather, it is that structure matters. To confront the growing pension crisis, states should undertake a sober examination of their plans and seek to design a retirement system that is fair to teachers and sustainable for taxpayers.

To better understand what happened with West Virginia’s pension reform, I look at their systems through the lens of two conventional myths levied against efforts to reshape teacher retirement systems.

Myth 1: State pension plans provide a more valuable retirement benefit for most teachers.

Many people consider a pension the gold standard in retirement benefits. And for those who teach for many decades, pensions usually do provide a valuable benefit. But this raises the question: how many teachers actually earn a high-quality retirement from state pension systems?

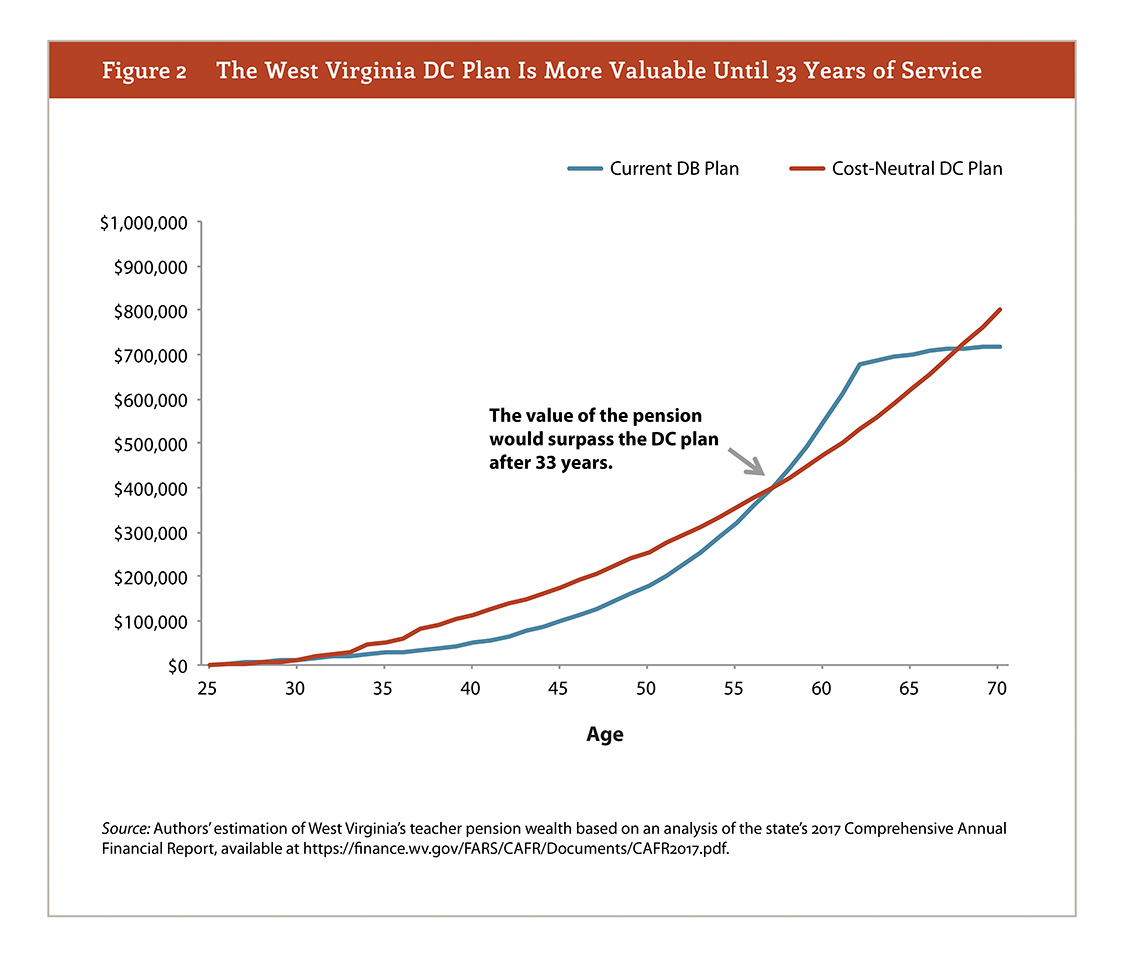

In West Virginia, the answer is not many. Due to the back-loaded structure of its pension plan formula, very few teachers in West Virginia actually reach an adequate retirement through their pension. As shown in the graph above, when wealth begins to accumulate more quickly, only about 40 percent of teachers will remain in the system. In other words, more than half of all teachers in West Virginia earn a subpar pension benefit.

Myth 2: Defined contribution plans are inherently inferior for teachers.

When West Virginia legislators sought to replace their pension plan, largely for cost reasons, they adopted a defined contribution plan. This was back in 1991, and the defined contribution plan the state implemented at the time was not well-designed to meet the retirement savings needs of its teachers. For example, the plan required teachers to serve 12 years before qualifying for full benefits. A shorter vesting period better aligns with teacher employment patterns. Indeed, that unusually long vesting period would be illegal in the private sector under federal regulations.

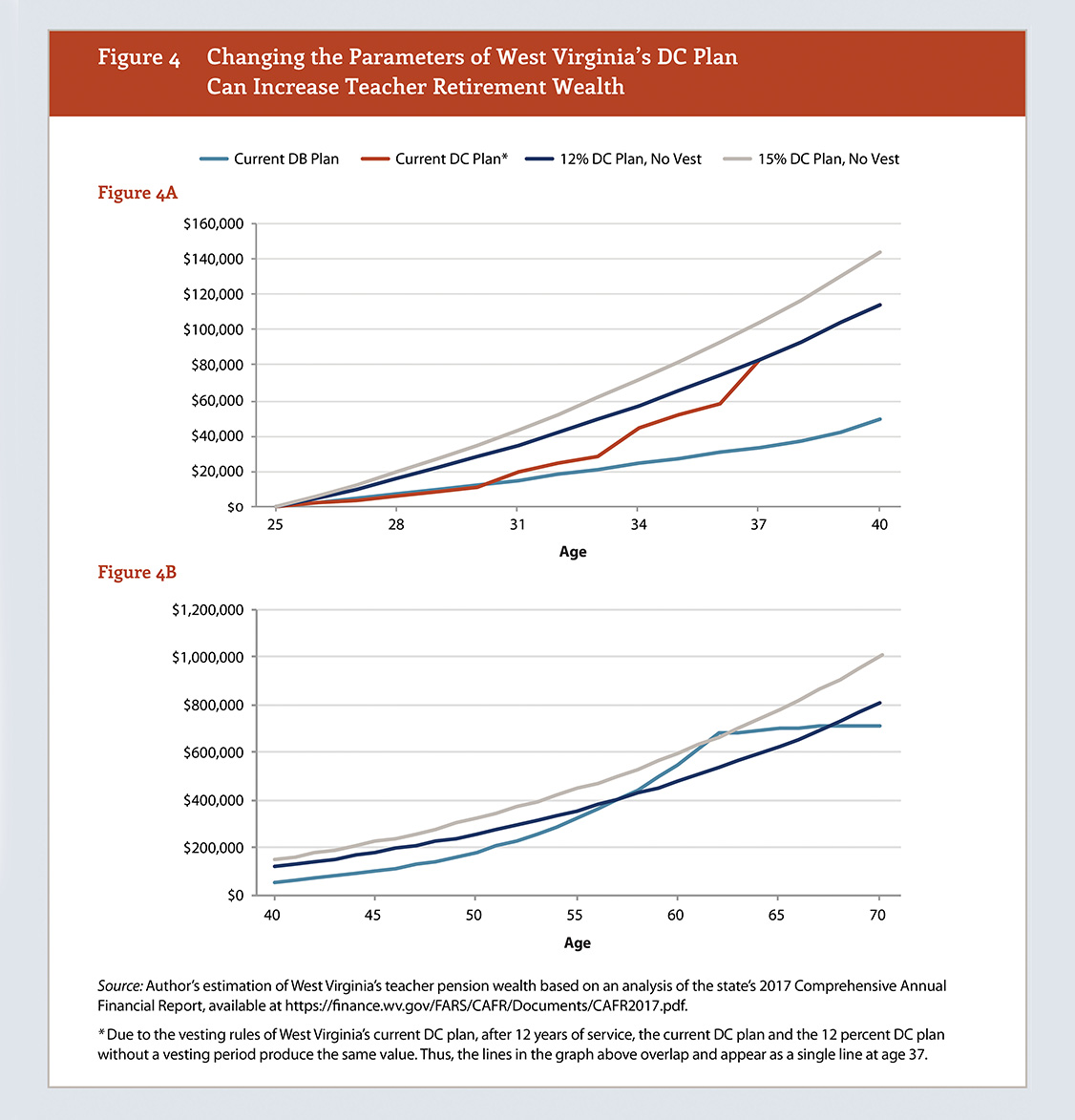

As with the old pension fund, thousands of West Virginia teachers did not meet the 12-year vesting threshold to benefit fully from the retirement fund. However, because West Virginia’s DC plan (as with all DC plans) does not rely on formulas based on years of experience as pension do, the fund nevertheless provided a more valuable benefit to most teachers when compared with the statewide pension. As shown in the graph below, it would take 33 years for the pension fund to generate retirement wealth more valuable than the DC plan. Only about 23 percent of West Virginia’s teachers will reach that point.

Myth 3: All DC plans are the same

West Virginia also serves as a useful reminder that a DC plan is not automatically better than a pension. Indeed, as my colleague Chad Aldeman wrote recently, it is possible for states to redesign teacher pension systems to better meet the needs of teachers.

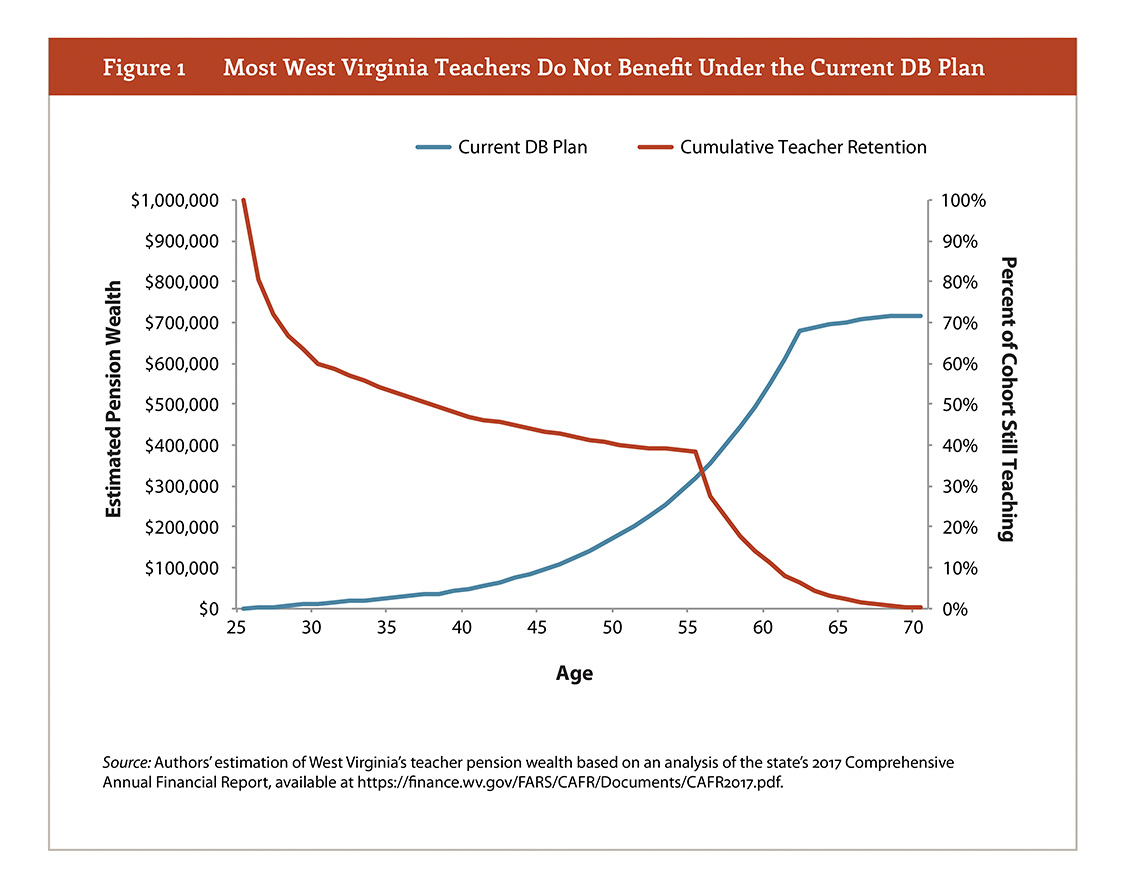

However, should a state elect to offer a DC retirement plan to teachers, they should think carefully about how to design such a system. Changing the structure of a DC, such as dropping the vesting period, or increasing the contribution rate can affect both plan’s wealth accumulation and its cost. In the graph below, I modeled two different DC plans that West Virginia – or any state – could adopt and compared them with the state’s current pension and DC plan.

A well-designed DC plan – if states decide that is what is best for their teachers and taxpayers, will avoid West Virginia’s missteps and be designed to include:

- Automatic enrollment of teachers into the program;

- The shortest possible vesting period for teachers to qualify fully for their retirement benefits;

- Employer and employee contribution rates that, at minimum, total between 10 and 15 percent;

- Low-cost options and life cycle funds that adjust an employee’s portfolio as she gets closer to retirement; and,

- An actionable and accountable plan to pay down unfunded liabilities.

West Virginia’s experience with pension reform should not be used as a cudgel against efforts in other states to address the growing pension crisis. Rather, it offers important lessons on how to more effectively adopt and implement changes to a statewide teacher retirement system. Learning these lessons is critical to effectively meeting teacher retirement needs as states continue to grapple with rising teacher benefit costs.