Illinois’ pension contributions have grown to over 20 percent of the state’s available general funds revenues; this limits other critical investments in education, social services and infrastructure, all of which are vital to the state’s growth.

This sentence appears in Illinois' official Fiscal Year 2021 budget book, released just a few weeks ago in late February. It's likely badly out of date already, as the state faces mounting health care costs and falling tax receipts in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak. Meanwhile, the state's pension systems are likely taking a massive hit in the stock markets, which will drive up pensions costs in the years to come.

This is not unique to Illinois, nor will it be new information to many of the state's residents. But it's striking to look at the trajectory over time to see just how much pension costs are strangling public education in the Land of Lincoln.

To get a sense of what that looks like, I collected data from the Public Plans Database on contributions toward public-sector pension plans. In Illinois, almost all of those contributions come out of the state's general fund, rather than being passed along to school districts or other employers. For my purposes here, I used something called "required contribution rates," which reflect the plan's best guess for how much the state needs to contribute in any given year in order to pay out future benefits down the road.

Next, I collected data on the state's direct spending on K-12 and higher education from the National Association of State Budget Officers. To get a sense of the state's spending on current students, I excluded expenditures on bonds and contributions from federal funds.

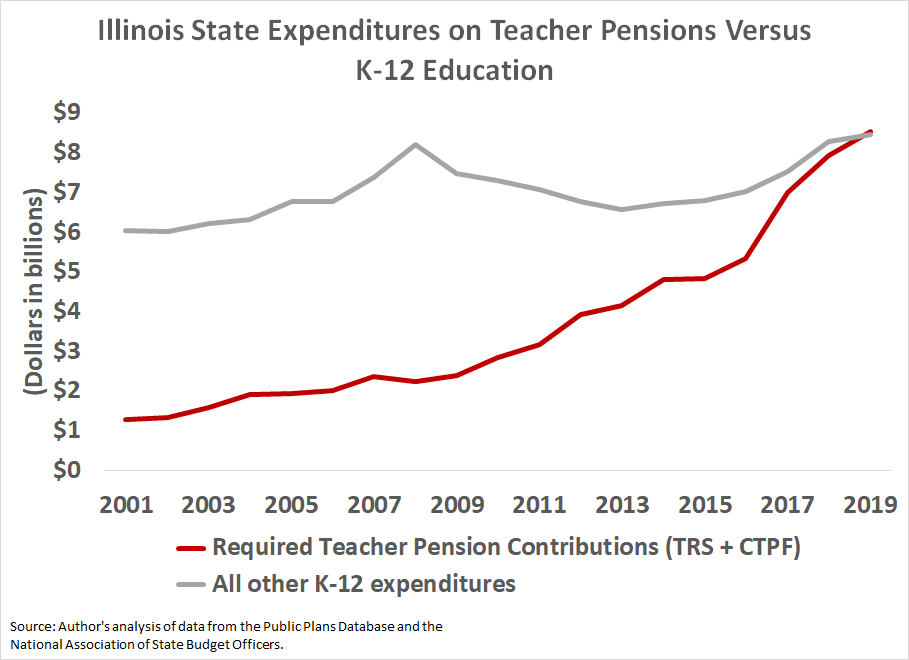

The first graph below shows the results on the K-12 side. As the gray line shows, Illinois' spending on elementary and secondary education has held up reasonably well. From 2001 to 2019, Illinois increased its K-12 expenditures by about $2.4 billion. Although this reflects the raw, unadjusted figure, Illinois' K-12 spending has also held up even on a real, per-pupil basis.

However, Illinois' required teacher pension contributions (represented by the red line in the graph) have increased much faster. Between the statewide Teachers' Retirement System (TRS) and the Chicago Teachers' Pension Fund (CTPF), the required teacher pension contributions have risen by $7.2 billion over the same time period. In fact, in 2019 Illinois' required teacher pension contributions surpassed what the state allocated for all other K-12 expenditures.

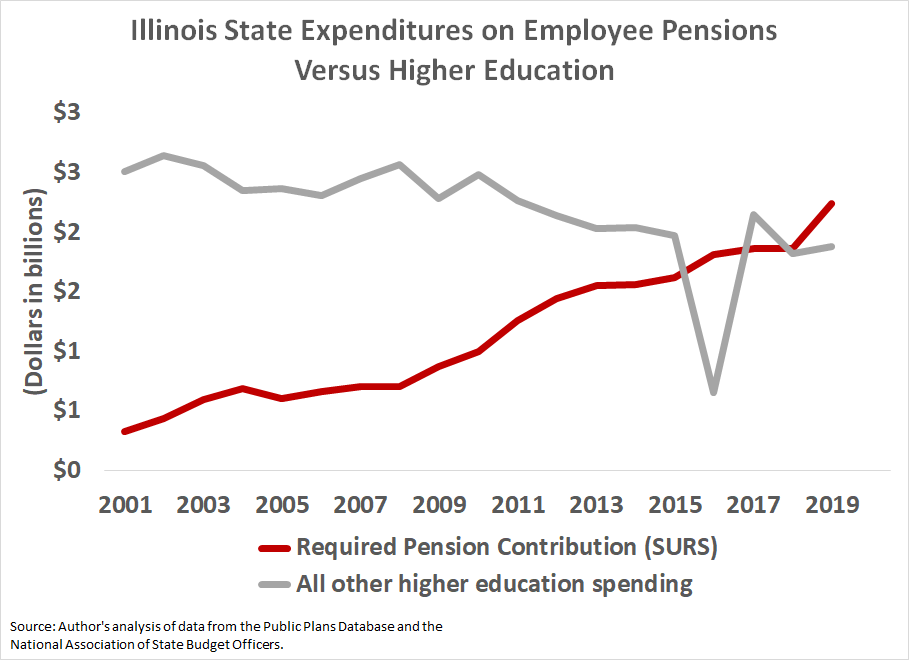

The story is similar for higher education, except that Illinois has not been able to protect its colleges and universities from budget cuts. Again, this isn't just an Illinois story, but states have been asking their public higher education institutions to do more with less, or else raise student tuition and fees to make up the difference. As in the first chart, the gray line in the next graph shows Illinois' declining support for public higher education.

The red line again represents required pension contributions, this time toward the State University Retirement System (SURS). Required pension contributions first surpassed the state's higher education spending in 2016, during a particularly bad budget year. The state's higher education budget has improved slightly since then, but the required contributions into SURS were again higher than what the state spent on all of its colleges and universities in both 2018 and 2019.

In raw dollar amounts, Illinois reduced its higher education spending by about $630 million over the last two decades. Again, that's in nominal dollars and is not adjusted for inflation or changes in student enrollment. Meanwhile, the required pension contributions into SURS rose by $1.9 billion over the same time period.

Of course, Illinois has not actually been making its "required" pension contributions. Over the last two decades, the state has contributed just 77 percent of what actuaries said it needed to pay into SURS, 70 percent of what actuaries estimated TRS needed, and just 56 percent of what CTPF neeeded. That adds up to billions of dollars that should be in the plans today if Illinois policymakers had been more responsible in years past. Those shortfalls have also contributed to the dramatic rise in the required contribution rates.

While it’s hard to pin down causality, this period of rapidly rising pension costs has been associated with benefit cuts for active workers, including both teachers and other public-sector employees. Due to legal protections, Illinois applied those changes only to new workers. In effect, those changes handed a disproportionately large bill to future generations.

Whether we’re talking about the effects on teachers or college students, Illinois and other states with high pension costs are punishing future generations to pay for the mistakes of the past.