In what counts as big news in the pension world, President Obama last week tentatively endorsed changing the retirement plan offered to military members. Under the proposal, military service members would shift from an all-or-nothing pension plan to a “hybrid” model combining a less generous pension plan, a 401k-style defined contribution plan, and cash bonuses paid out at various career milestones as retention incentives.

There are three important political developments here. First, the big one: President Barack Obama is now on record in favor of pension reform. The final report from the Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission made it clear they supported reforming the pension plan because it was good for workers. This is a tremendously important signal within a broader context where pensions are often treated as a third rail> political issue that cannot be touched.

Second, it’s a sign that the politics of pensions may be changing as people start to realize that pension systems with a few big winners at the expense of lots of small losers is not a good retirement policy. All workers need a path to a secure retirement, not just a select few. But with less than 20 percent of the military’s enlisted personnel staying the requisite 20 years to qualify for a pension, it’s clear that the current pension plan is not providing sufficient retirement savings to the vast majority of the military.

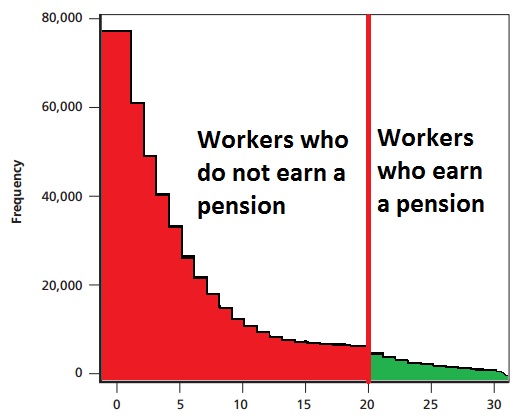

The chart below, modified from a RAND report commissioned by the military, shows a profile of the existing military enlisted workforce. The vertical bar at 20 years represents the pension requirement. Workers who stay less than 20 years get no retirement benefit at all, while those who do qualify for a pension worth at least 50 percent of their salary. The majority of workers have five or fewer years of experience, and only a fraction of workers even approaches the 20-year mark.

Teachers are in a similar albeit not as extreme predicament. The teaching workforce has relatively high early-career turnover that flattens out over time. Teacher pensions are not all-or-nothing, but only about half of new teachers will qualify for some pension. The rest leave with only their own contributions, sometimes with interest. Because teacher pension benefits are heavily back-loaded, the Urban Institute estimates the median state requires teachers to stay at least 24 years before they hit the “break-even” point where their pension is finally worth more than their own contributions plus interest. Less than one-quarter of new teachers will reach that point, and less than one-in-five new teachers will remain in a pension plan long enough to reach the normal retirement age set by state lawmakers.

The question facing pension advocates is how long they want to protect this unequal and unfair system. Will they keep defending pension plans where a few teachers get solid retirement benefits at the expense of the majority? Or will we move to retirement systems that provide all 3 million teachers with a solid path to retirement?

The third political shift worth noting is that data are busting the myth that pensions are good for worker retention. For example, the graphs showing how little the military’s current pension system affects worker retention are striking. In contrast to theoretical arguments on pensions and retention, the best available data suggest pensions are not a strong retention incentive for most teachers either. Any efforts to dramatically alter retention rates must aim at the large group of workers who leave early in their careers. Back-loaded pension benefits simply cannot alter the behavior of most workers.

President Obama’s actions signal a small shift in the political winds on pensions. As evidence mounts showing how poorly structured pension plans fail to meet the needs of today’s workforce, let’s hope more politicians make it a trend.