In Georgia, K-12 school teachers are automatically enrolled in a defined benefit pension plan.

In contrast, at Georgia’s public colleges and universities workers are given a choice between the same pension plan or a defined contribution plan.

Why don’t K-12 teachers have the same choice as their peers in higher education?

Georgia's K-12 teachers deserve a better choice, because the current plan run by the Teachers Retirement System (TRS) of Georgia plan is poorly designed for the vast majority of its enrollees. The TRS pension plan requires a 10-year vesting period before workers qualify for any retirement benefits; this is so long that it would be illegal in the private sector. Georgia also does not provide Social Security coverage to all of its K-12 teachers, leaving some teachers entirely dependent on their TRS benefits. And yet the TRS formula delivers adequate benefits to only a fraction of members who remain teaching in Georgia for their entire career.

The vast majority of Georgia’s K-12 teachers would be better off in a plan offered to the state’s higher education employees. Unlike elementary and secondary teachers, workers at Georgia’s public colleges and universities are allowed to choose between either the TRS plan or the Optional Retirement Plan (ORP). Originally designed for university professors moving across higher education institutions, the ORP also has a number of features that would be attractive to K-12 teachers.

In contrast to the TRS plan, the ORP offers immediate vesting, which means that all workers begin accruing retirement benefits immediately, starting from their first day on the job. Georgia higher education employees are also covered by Social Security, meaning they receive a nationally portable, progressive benefit that many of Georgia’s K-12 teachers lack.

It may sound counter-intuitive, but the ORP is simultaneously more generous to employees and less costly to employers. It’s due to how each plan works. The TRS plan is based on a series of assumptions. It offers benefit through a formula, and the state estimates how much those benefits will be worth down the road and how much the plan needs to invest today in order to pay for those future benefits. When the state is wrong about any of those assumptions, or when it fails to save sufficiently, pension plans can accrue unfunded liabilities. Today, Georgia school districts are paying a total of 20.9 percent of each teacher’s salary into the TRS pension plan, but only about one-third of that (7.7 percent of each teacher’s salary) is going toward benefits for workers. The rest (13.13 percent of salary) is going to pay down those unfunded liabilities.

In contrast, the ORP has no unfunded liabilities, and it never will. Under the ORP plan, a worker's benefit is defined in terms of how much is contributed into the plan, and how fast those investments grow. There are no assumptions to worry about, and hence the plan will never accumulate unfunded liabilities. Georgia’s colleges and universities today are contributing 9.24 percent of each participating employee’s salary into the plan. That is both more generous to workers than the TRS plan (9.24 versus 7.77 percent of salary toward benefits) and less costly overall (the same 9.24 in ORP versus the total 20.9 percent in TRS).

Comparing Key Elements of Georgia Retirement Plans

| Teachers Retirement System of Georgia (TRSGA) | Georgia Optional Retirement Plan (ORP) |

Vesting period | 10 years | Immediate |

Employee contributions | 6.0 percent | 6.0 percent |

Employer contributions for benefits | 7.77 percent | 9.24 percent |

Employer contributions for unfunded liabilities | 13.13 percent | N/A |

Total employer cost | 20.9 percent | 9.24 percent |

Social Security coverage | Varies, depending on school district | Yes |

There is one other element we haven’t discussed yet, and that is fairness. The ORP plan is more generous to participating workers on average, and it treats all workers the same. Every ORP plan member contributes the same percentage of their salary, and every ORP member receives the same percentage* contributed on their behalf.

In contrast, the TRS plan does not distribute benefits evenly. Its formula awards disproportionately large benefits to teachers who stay for 30 or more years, while leaving everyone else with substantially less. The 7.77 percent employer contribution that's going toward benefits in the TRS plan is an average across all members. Some teachers will eventually qualify for benefits worth much more than that, while many more will qualify for less.

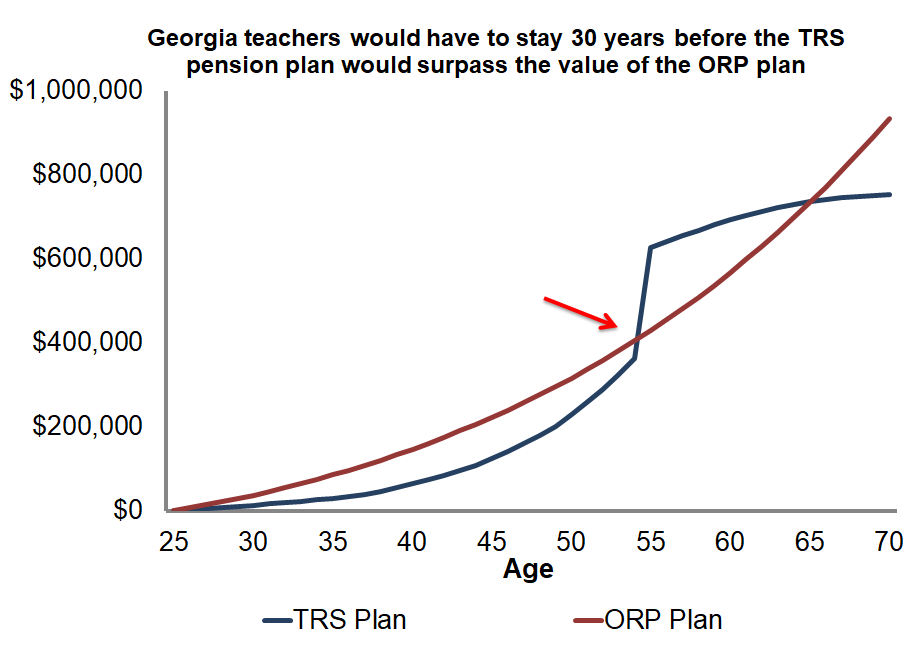

The graph below shows how benefits would accumulate for teachers under the TRS pension plan versus the ORP. As mentioned above, the plans are not cost-neutral, and I’ve assumed a more conservative rate of return in the ORP plan than what TRS assumes. Still, the ORP would provide more value than the TRS plan for this hypothetical teacher’s first 30 years of service as a teacher in Georgia.

This graph also does not include Social Security; it’s purely a comparison of the two state-provided retirement plans. After factoring in Social Security, it's clear that participants in the ORP are receiving much more generous retirement benefits than teachers in the TRS plan alone. While some teachers might still prefer the pension plan, Georgia should at least give its K-12 teachers the same choices offered to the state's higher education employees.

*Note: The actual dollar amounts contributed will vary based on a worker’s salary, but that’s true in both the ORP and TRS plans.