Yesterday, the Thomas B. Fordham Institute released my new paper on the retirement plan options offered to Ohio teachers. Since 2001, the Buckeye State has given new teachers a choice over three different retirement plans--a traditional defined benefit pension plan, a 401k-style defined contribution plan, and a combined plan that includes elements of both. If a teacher makes no affirmative choice within 180 days of employment, Ohio automatically puts them into the traditional pension plan.

In the paper, I walk through the reasons why Ohio should change its "default" setting from the pension plan to one of the other options. But why does it matter? Won't teachers make the best decision for their own lives regardless of what the default setting is?

As I write in the paper, there's abundant evidence that workers listen to and respond to defaults. Whether that's simply because of inertia or because workers view the default choice as a form of profession advice, defaults do affect people's behavior:

Research from the private sector has found that employee defaults like the one employed by Ohio STRS can be powerful mechanisms. Workers, especially new ones, have a lot to figure out, and when given an option to join an employer-provided retirement plan, many new employees fail to make decisions. When employers switch the default option to assume automatic participation, enrollment rates jump 25 to 35 percent. Similar research has found that employees are likely to follow default options on contribution rates and investment decisions. None of these choices are mandatory, but this body of research suggests there are ways to “nudge” workers into making smart decisions.

Although it didn't make it into the paper, I wanted to show you an example of the power of defaults and nudges in the public sector.

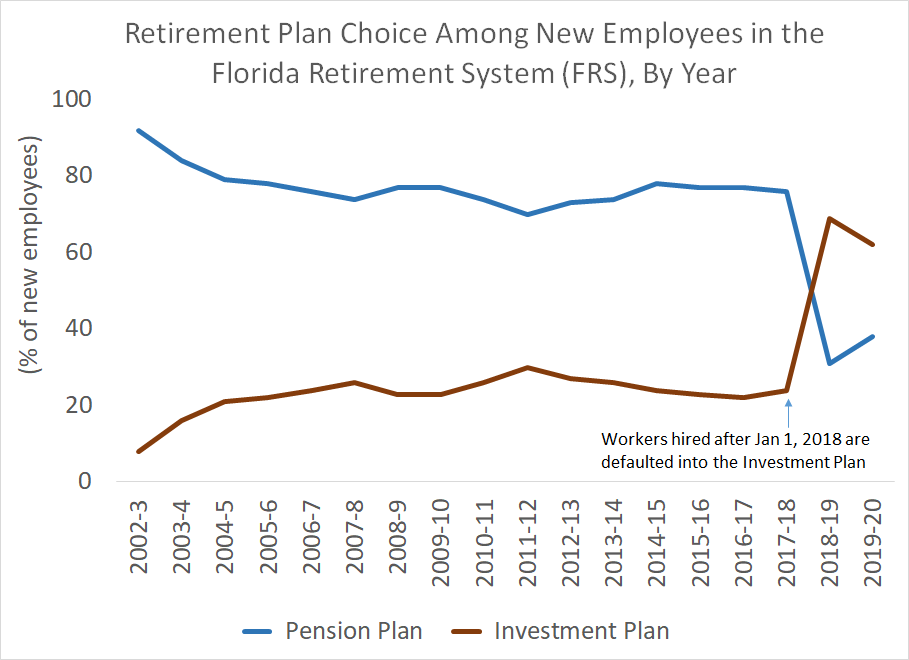

It comes from Florida, which is on a similar path as Ohio. Starting in 2002, Florida began offering its public employees a choice over two plans run by the Florida Retirement System (FRS). FRS includes teachers and other education employees, but it also includes other types of public-sector employees. Starting with new hires as of January 1, 2018, Florida switched the default option from its Pension Plan to its Investment Plan.

The graph below shows what happened next. Before the switch, about one-quarter of new employees were selecting the Investment Plan, and about three-quarters were selecting the Pension Plan. Immediately after the state changed the default option, those numbers reverse. In the two years since the change, about two-thirds of workers are enrolling in the Investment Plan, and only about one-third are selecting the Pension Plan.

Another way to look at this is to look at the percentage of employees who actively choose a plan, versus those who merely default into one of the options. In Florida, those numbers have held relatively steady over time: About half of all new employees make an active decision into one of the two options, while the other half simply defaults into whatever plan the state recommends. (See here for the raw numbers.)

Florida made its decision based on the evidence in their state. As FRS was trying to educate employees about their choices, they published a graph showing that all workers hired under the age of 45 would be better off in the Investment Plan. Even for those workers hired over the age of 45, FRS estimated they would need to remain in the system for more than eight years before the Pension Plan would be a better deal. That sort of evidence was enough to convince Florida legislators to make the shift.

My paper shows that Ohio legislators have similarly compelling evidence about what plans are best for its teachers. Every year that passes is another year where the state has to cut benefits and raise contribution rates into its Pension Plan. Meanwhile, school districts are contributing 14 percent of teacher salary into the Pension Plan, but none of that money is going toward worker benefits; it's all going to pay down the pension plan's unfunded liabilities. As my analysis made clear, Ohio teachers would be better off in either the Combined or the DC Plan, regardless of how long they serve.

It's important to note here that we're not talking about taking any choices away from people. In both Florida and Ohio, workers already have a choice over their retirement plan. The question is merely what plan the state(s) should recommend for workers who make no decision. Changing the default option would not affect current teachers or retirees. And they would not take away choices for new employees. But Ohio could make a simple change to put more of its educators on a default path to a secure retirement.