Teacher pension plans are extremely back-loaded. They offer short- and medium-term workers--the majority of all teachers--very little in the way of retirement benefits.

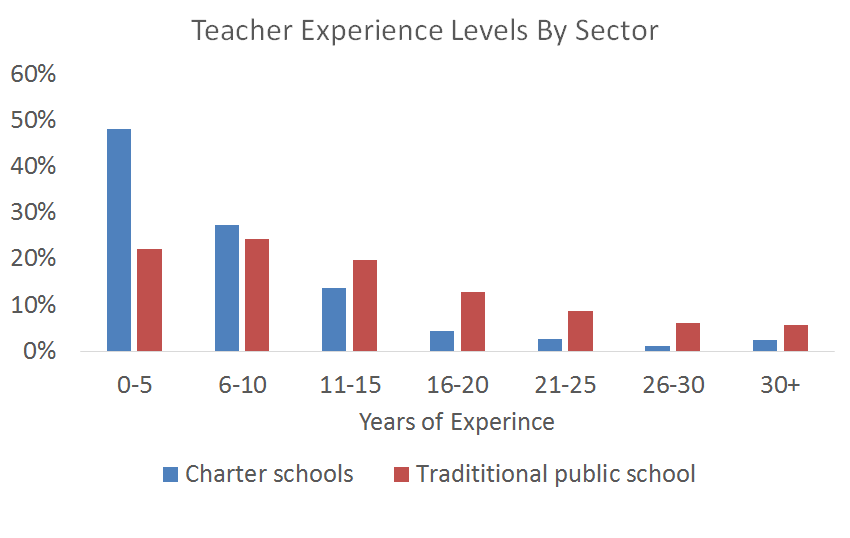

The graph below shows an example of how retirement benefits accumulate under a traditional pension plan. For a teacher who begins her career at age 25, she won't have much in the way of retirement savings for the first 10 or 20 years of her career. Then, if she's still teaching, her pension benefits will escalate quickly as she nears the state's normal retirement age (in this example, it's 60.) After age 60, her pension benefits will actually start to decline, because every year she continues teaching is a year she won't be drawing her pension. The pension plan will give a strong financial "push" for teachers to leave teaching.

This arrangement is bad for all teachers because it leaves them without sufficient retirement savings for long stretches of time. Half of all teachers won't qualify for a pension at all, and another group of mid-career teachers will qualify for only a meager pension. Only a small fraction will reach the back-end and truly maximize their pension.

But this arrangement is particularly bad for groups of teachers with high turnover rates. That includes urban and rural teachers, teachers in certain subject areas, and teachers in charter schools.

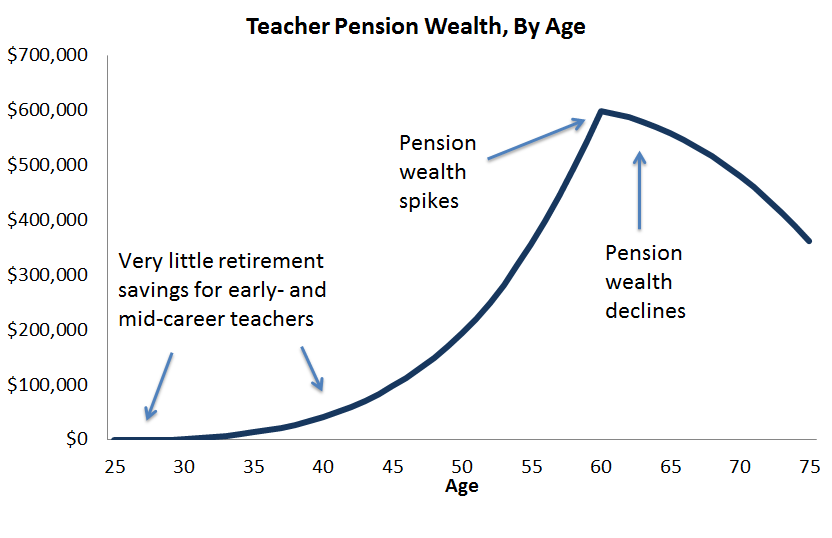

Charter school teachers are some of the biggest losers under current pension plans, because very few charter school teachers have worked long enough to qualify for the back-end benefits offered by traditional pension plans. The chart below compares experience levels in charter schools versus traditional public schools. The data come from the 2011-12 Schools and Staffing Survey, and they show the charter sector as a whole has teachers with significantly less experience. About half of all charter teachers had five years of experience or less, and two-thirds of charter school teachers had 10 years or less. In contrast, traditional public schools had three times more teachers with 20 or more years of experience, and almost four times as many teachers with 25 or more. In other words, few charter school teachers have accumulated the experience necessary to claim the real rewards from state pension systems.

Charter schools are still relatively new, so some of these disparities may be due to the fact that charter school teachers haven't had enough time yet to age into the profession. But charters also have higher annual turnover rates, suggesting that fewer of their teachers will ever truly benefit from existing pension systems. And, in the meantime, charters are on the hook for paying off large legacy costs of accumulated pensions debts. These legacy costs are so high today that new teachers will never accumulate benefits worth more those contributions. This is true for all teachers, not just charters, but charters participating in pension plans will have to contribute the same amount as all other schools, even if their teachers aren't benefitting and they weren't responsible for the accumulated debt.

In other words, pension plans should thank charter schools for subsidizing their past debt. Meanwhile, charter schools should think about how to provide retirement benefits that more closely match their workforce.