Pensions are complicated. Here at TeacherPensions.org, we try to break down those issues and make pensions more understandable for teachers, policymakers, and the general public. There are other groups doing great work on the pension issue as well, and yet myths persist and actual policy successes are still too rare.

A new organization called the Retirement Security Initiaitve (RSI) is trying to break that logjam. To learn more about their work, I spoke with Dan Liljenquist, a member of RSI's Board of Directors, and a former Utah State Senator who helped steer groundbreaking pension reform through his state's legislature. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation:

Aldeman: Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you came to work on the pension issue?

Liljenquist: Well, I was elected to the Utah State Senate in 2008 and when I met with the Senate President that day, he gave me an assignment to serve as the chairman on the retirement committ

ee with what, at the time, he felt were comforting words. He said, “Don’t worry, nothing ever happens over there.” I took office right at the bottom of the 2008-9 financial crash, and all of a sudden we had a major pension issue on our hands.

Utah has always done the right thing with its pension system. We fully funded it every year. We set pretty reasonable benefits. But one year’s worth of market losses blew a 30 percent hole in our fund. We realized that paying off those losses would be the equivalent of taking 8,000 school teachers out of their classrooms for 25 years to pay off one’s year worth of market losses. We knew we had a system that needed to be reformed.

I got involved in the State Senate as the Chairman of that committee, and in 2010 we ran reforms that moved all new employees into a retirement contribution style plan that capped the liabilities to the state moving forward but also still provided adequate retirement security to the new employees.

Can you say more about that last part? There are a lot of critiques about defined contribution plans. What steps did you take to provide retirement security for all workers?

There are a whole bunch of ways you can do defined contribution plans. When people think of defined contributions, they usually think of standard 401k plans. That’s not what we did in Utah. When we say defined contribution, we set a defined amount that the state was willing to pay towards retirement for its workers, and we gave people a choice for how they could receive those contributions: They could enroll in a 401k-type plan that was professionally managed with low fees, or they could use the contribution from the state—again, a set amount—towards a defined benefit/ defined contribution hybrid plan. In the latter option, the state would still have its contribution capped and the employees would have to kick in any excess contributions if the defined benefit portion went beyond the state’s pre-determined contribution amount.

From a state perspective, this allowed us to cap the liability for state taxpayers while letting workers choose a benefit structure.

Can you tell us about your new work with the Retirement Security Initiative? What do you hope to accomplish?

We realized there are a lot of people out there doing really great work on the 501(c)(3) side educating people about the pension issue. In fact, we see better analysis and better understanding of pension-related issues than ever before. But what we realized is that there’s a gap between having the analysis and actually getting reforms passed. It’s a very complex issue, and it’s very difficult for policymakers to move forward. They have to not only piece together all of the information and make sure they have the relevant facts and policy levers to craft solutions that work for their jurisdiction, but it’s also it’s very difficult to move this issue forward when opponents of these types of reforms scare people and say that reforms will damage individuals and the retirement of current employees and retirees.

So typically it’s very difficult for a legislator to do this on their own. I learned that personally, it was exceptionally difficult for me to do and I had almost no support. So with the Retirement Security Initiative, we created a 501(c)(4) organization to address this need. We are an issue advocacy organization, and we have three main goals.

One, we want to make sure that retirement systems meet every penny of the commitments they’ve made to current employees and retirees. This means that they need to fully fund their pension plan, they have to adopt good governance, and that the legislature is committed to meeting all of the commitments they have made to current employees and retirees. We want to make sure people get the pensions they deserve.

Two, we advocate new systems for new workers that are predictable in their costs and sustainable in the long term. One of the challenges with defined benefit systems as they’re currently constituted is they must try to make 60- or 70-year projections about how long people will live and how the stock market will do, and invariably those assessments tend to be too rosy in the out years. That means governments don’t pay as much today as they should. We’re interested in plans that are more sustainable and that ensure benefits are fully funded as promises are made, rather than back-loading costs.

Three, those new plans should provide adequate retirement security to new workers. It would do no good to eviscerate retirement for new workers in order to solve the budget problems of today. We want to make sure that any new plan puts in sufficient resources to ensure that workers can get to 60-70 percent income replacement by the time they reach retirement.

So, in short, we want to make sure plans meet their current commitments, new workers are put in more sustainable plans, and that those new plans provide adequate retirement security.

I’d love to drill down a little bit on this distinction between protecting the benefits for existing workers and retirees versus creating new plans for new workers. How do you think about communicating that nuance to legislators or the general public?

I think there’s a tendency to blame plan participants for accepting the current defined benefit plans. That is absolutely irresponsible to do in my opinion, because plan members took a deal that [state and local governments] offered them. That’s why I think the first priority is the commitment to current retirees and employees. Policymakers may not like that deal, but it’s the deal that’s been offered and accepted. If it ended up being a good deal for the workers, why should we be upset that somebody took a good deal that was offered to them?

Now, there’s some concern that the benefits for new workers are not rich enough and they’ll face significant hardship. We found that not necessarily to be the case. Obviously there’s going to be a transition period, but in many cases we’re actually advocating a little bit more money into retirement to avoid the long-term risk down the road. And so I think there’s when you look at the new plan you have to make sure that that new plan is independently analyzed and really look at the longevity of your employees, how much money you need to put away, what’s a reasonable return you can expect on those investments, and then kind of back in to what you need to contribute to get to a 60-70 percent replacement rate. That is standard actuarial science.

One of the things that traditional defined benefit plans have struggled to do is to keep up with the needs of new workers, and portability is one of those needs. In order to lower the cost of the plans, some plans have a 10-year vesting requirement. That means if you leave before 10 years, you get nothing. Particularly in the education space, states have tried to keep costs low for career workers, but in the process they hurt new workers or short-term workers, people who come in and teach for a few years and then move on to something else. In designing new plans, states can actually repair some of those inequities of the old-time benefit plans. It’s about understanding the various levers and understanding what your policy objectives are. Typically policymakers want more predictable retirement costs and want more portability to meet the needs of the new workforces. Those two priorities help frame reform efforts and guide policymakers to an acceptable solution.

Can you talk a little bit about how you will approach the work and what you think might be the biggest challenges?

Our approach at the Retirement Security Initiative is to work directly with legislative leaders who are interested in this subject. We work to make sure they are connected with various 501(c)(3) organizations out there doing pension work, such as the Pew Charitable Trust, the Reason Foundation, and others, to make sure they have the analytical resources to analyze different options and to understand different policy levers and how other states have used those levers. Occasionally we will express our own principles in relation to certain aspects as legislation gets drafted, but our main goal is to help legislators move legislation and get it done. We typically work with lobbyists in each state and make ourselves available to help policymakers talk about pension reform in a way that brings people along instead of polarizing people on the issue.

And do you see any bright spots out in the field? You can point to your own work in Utah, but are there other places you would point to for future legislators who might be interested in tackling this work?

One day, everybody is going to have to deal with this issue. I’ve been working on this issue for six years, and I’ve been encouraged that, as more and more data comes out, I see more and more interest in doing something meaningful. Part of that is the financial crisis really strained state and local budgets around the country, and if things get worse, some of these governments are going to be hard-pressed to continue to operate and meet their commitments. The sense of urgency has risen quite a bit. That’s the first step, you have to have a sense of urgency to do something.

I’ve also been encouraged by the major reforms over the last couple years in Utah, Kansas, Rhode Island, Kentucky, and Oklahoma. Pennsylvania is on the verge of reform, and Arizona passed a major reform for its public safety workers earlier this year with the direct participation of its police and fire union, so I’m encouraged that people are ready for reform. Again, when you explain that the objective is to help state and local governments keep their commitments to workers and retirees, it becomes an issue that everybody should be able to get behind.

What would be your first word of advice to a legislator who is interested in taking up this issue or learning more?

The first step is to learn your own system. There is no one-size-fits-all reform. Every need is different. Every state and city is different. And every state and city comes from a different governance angle. Workforce needs are different. Competitive marketplaces are different. So I recommend understanding your own system and how it’s working. There are a lot of great resources out there on specific states and external support to do targeted actuarial analyses on specific plans. You have to understand what the problem is before you come up with the solution.

Perhaps the most important message is reality is not negotiable. One day, every state will have to address this issue, and the earlier they address it, the more options they will have. Groups like the Retirement Security Initiative are here to help.

Taxonomy:- Shirley Ben-Ami was a teacher for nearly 35 years. She taught fourteen and half years in the New York City Public Schools and spent the last 20 years in Montgomery County, Maryland. She mostly taught English in middle schools. Her favorite thing about teaching was the relationships she formed with her students. She retired just a few months ago. In the interest of full disclosure, Shirley is my fiancé’s mother. I began talking with her about teacher pensions after I started working at Bellwether a few months ago.

The following is a lightly edited transcript of a recent conversation.

Max: Before we talk about your experiences retiring from teaching, I’d like to hear a bit about what got you into the profession in the first place.

Shirley: Well, it’s a little bit embarrassing, but I originally didn’t do it out of any passion. I was an English literature major at NYU, and I couldn’t decide what I wanted to do with my life. It was 1971, and I had a few acquaintances who were going to law school, but I didn’t know any women going to medical school. It seemed to me in that day and age, women went to college to get a job for a few years, maybe in publishing, and then they got married.

Although it was the start of women’s lib, I still thought that marrying someone, having a beautiful home, and not having to worry about money was what I wanted. Even though intellectually women’s lib resonated with me, it was still somewhat new. It wasn’t something that I thought much about: Why don’t I go to law school? Why don’t I get an MBA? In fact, when I was in high school, the predominant pathway for women was to go to college and then on to secretarial school, such a as Katherine Gibbs, a well-known secretarial school for college grads. And then get a job as someone’s executive assistant.

So I decided that I better get an education degree since I needed to do something. I took all the courses and I took all the tests, but there weren’t any teaching jobs available in Manhattan at that time. So in the meantime, I got a job at Lord and Taylor as an assistant buyer. It sounded exotic to me, even though it was entry level. I made $7,000 a year. While I was there, I found out that the men in my position were making around $1,500 more. And at that low salary, that’s a huge difference! This really hit home for me. It was the first that I can really recall thinking about being a woman in the workplace. I went into the manager’s office and asked him about the gender pay gap. He replied, in a very nice way, as though it made sense, “You know, men have families that they have to support.” He didn’t think that was outrageous. I thought it was unfair, but I guess I accepted it as how things were.

I started trying to get jobs as a substitute teacher. Every time I found one, I would call-in sick to Lord and Taylor since I couldn’t afford to quit. I was asked to work at the same school quite a lot, so I got to know and become friends with the teachers and administrators. Eventually I got a job there. This took about a year in total. My first job was at Junior High School 56 teaching science since they didn’t have any English positions. I switched to English after about a year and a half.

Max: When you moved to Maryland, did you think much about your retirement or what to do with the money in your pension?

Shirley: When I left New York retirement didn’t enter into my thinking at all. I was moving to get married. I was 38 years old and I had previously decided that getting married and having a family wasn’t going to happen to me. So falling in love and having a family – he already had three children – was very appealing to me. (Editor’s note: New York City raised the vesting period from 5 years to 10 years in 2009).

No one at my school in New York City was really talking or thinking about retirement. The question only sort of came up during my last year—should we invest a few bucks with Fidelity or buy 20-year bonds? Interest rates were really high at the time so some teachers decided to put a little money away.

But since I was moving to Maryland for a new life, I gave it up and withdrew what little money there was in my pension fund. There was no question in my mind that I was doing the right thing. Not one of my friends said, you know you should keep the money in the pension or try to roll it over into another kind of account. It just really wasn’t on people’s radar. Most of us didn’t think about retirement, or what was going to happen in 30 years. Now I realize that was foolish on my part.

These days it seems like younger people do think more about retirement. It’s probably thanks in large part to their parents because we can see what a difference it would have made had we started saving when we were younger. You are all so much wiser than I was at your age.

Max: So now you’re living in Maryland, you have three kids from your husband’s previous marriage and quickly two of your own children. How did you handle your retirement then?

Shirley: I still didn’t think all that much about it at first. I had always heard that Maryland had a poor pension system—at least when I started in 1996. But then I got divorced, I didn’t have any savings, and I was on a single income without any child support.

It was a huge wake-up call.

I knew then that I had to put away as much money as I could. I went into HR, signed all of the papers for their 403b option. At the time the maximum I could contribute was around $10,000 per year. I always signed up for the max. Since I was putting away as much as possible, the fund has grown quite nicely even though it has only been 20 years. At 46 years old, retirement didn’t seem all that far off.

I wouldn’t be able to retire on my pension alone. In fact, the 403b is actually worth more per month than the pension. I’m just so fortunate that I had my mother, who helped financially; otherwise I don’t think I would have been able to save enough for retirement and support my family.

Max: You taught for over 30 years and yet, your pension alone is insufficient to retire on. That’s kind of incredible. What would you change about teacher pensions so that they can better serve teachers?

Shirley: I’m not really qualified to answer that. Is it fair to say that health insurance costs, even with Medicare, are just so much of a burden? Now that I’m making less money, I have to pay so much more for my insurance. I am participating in the Montgomery County health insurance plan, but the retiree has to carry a lot more of the burden.

I also think that – since you mentioned that a lot teachers don’t have the option of a 403b plan – that districts should provide teachers with that option. As I said, I couldn’t retire without it so I imagine other teachers would benefit from it as well.

Finally, I think that teachers should be able to take their pensions with them. It’s kind of absurd that I’m effectively paying a penalty for working, and for a long time, in two different states. People move and that shouldn’t cost teachers money.

Max: What do you wish you’d known about pensions when you were teaching?

Shirley: I can’t tell you how much I wish I could go back and realize that retirement age comes sooner than you expect. And it’s insane the way I just didn’t think about what my future would be like when I was young. It seemed so far in the distance that I couldn’t see that clearly that far off. I wish I had known more about teacher pensions. I also wish I knew then that I couldn’t bring my pension with me when I moved to Maryland. Keeping two different pensions means less money In the long run. With that in mind, I would have started to contribute to a 403b so much earlier.

Max: What advice do you have for new and current teachers?

Shirley: Contribute everything you can from the first day! Retirement comes so much sooner than you think. And make sure that you know your state’s vesting rules so that you can be sure to keep all the money that was contributed on your behalf to the pension fund.

- A former teacher, Kevin L. Matthews II is a licensed financial advisor, author, and speaker. Kevin holds a bachelor's degree in Economics from Hampton University and is a candidate for the Certified Financial Planner (CFP) designation through Northwestern University. In 2010, Kevin launched BuildingBread to inspire millennials to set, simplify and achieve financial goals. Kevin regularly speaks to young adults across the country and has been featured in media publications and productions including The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, LearnVest, NerdWallet, and many others. We reached out to Kevin to hear more about his decision to leave the classroom, and how teachers can best prepare for retirement.

Below is a lightly edited transcript of my recent correspondence with Kevin.Kirsten Schmitz: Thanks again for connecting with us. We have a few biographical questions to set up some context. Where and what did you teach?

Kevin Matthews: I taught 7th grade math at Ann Richards Middle School in Dallas, TX.

Schmitz: How long did you teach?

Matthews: I taught for two years, from 2012 to 2014.

Schmitz: Can you tell us more about your decision to both enter and exit the classroom?

Matthews: I entered the classroom in 2012 with the belief that a great education was the "master key." With it, there is no door or opportunity that cannot be unlocked. I still believe in that ideal today. Currently, I am still the only four year college graduate in my family; that accomplishment has unlocked opportunities I didn't know existed for people who looked like me. Teaching was a chance to show others how to knock down barriers and carve out their own path to success.

My decision to leave the classroom however, was a difficult one. I still question if I've made the right decision. My choice to leave the classroom came down to one of education's primary causality dilemmas. Does education limit income or does income limit one's education?

It is likely some combination of both, but I ultimately sided with the wealth and income portion of the equation. I thought leaving the classroom to become a financial advisor would give me a better chance at helping people avoid massive student loan debt and create generational wealth.

Though I enjoy the privileges of helping families plan out their financial goals, I often find myself helping current and former teachers figure out how their pensions work and the best way to approach their retirement strategy. For all the amazing work teachers do to prepare students, we need to do a better job of helping teachers prepare for retirement by giving them pension options that fit today's economy.

Schmitz: Since you've left teaching, what did you do with your retirement account balance?

Matthews: I rolled my account balance into a Traditional IRA in the summer of 2015.

Schmitz: What do you wish you had known about your retirement benefits going into teaching? Or, is there any advice you'd like to pass along to future teachers?

Matthews: I really wish I had known what all my investment options were and for someone to explain the pension plan in context, without bias. When I started contributing to my retirement I was told I could only choose variable annuities, which can be expensive. It wasn't until my last year that I learned I had more investment options such as mutual funds which would have been more beneficial for my situation.

My biggest piece of advice for future teachers is to really sit down, take the time to understand your retirement benefits and how they'll affect you. If you're approached by an advisor on campus, do not make a decision after just one meeting. Give yourself enough time to do your research and work with someone who will walk you through it and explain how the pension works.

If you’re a teacher or former teacher who enjoys reading our work and would like to tell us your story, please contact us at: info@teacherpensions.org. We can't promise to interview everyone, but we are interested in hearing how state and local retirement systems impact the lives of individual teachers, whether you are early in your career, in the middle of it, nearing the end of a long career, or have transitioned out of teaching.

Taxonomy: Change isn’t easy, and the large-scale shift from defined benefit pension plans to 401k-style plans has had its own bumps and missteps. A new report from the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College (CRR) helps document how that transition is going.

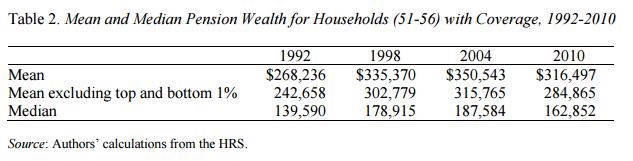

The paper looks at retirement wealth of households headed by 51-56 year-olds from the period 1992 to 2010. Before digging into their findings, it's worth noting that 2010 was a difficult year for savers. As a country, we were still coming out of one of the worst recessions ever; unemployment was high, and some employers cut their retirement contributions. Still, the findings here suggest that the transition from DB to DC plans has been turbulent but is not leaving workers materially worse off than they were before.

Here are some takeaways:

- In inflation-adjusted dollars, retirement savings in 2010 were lower on average than in 1998 and 2004, but they were higher in 2010 than in 1992. The median values (see table below) are especially pertinent, because they show that the overall increases aren’t just being skewed by high-income workers.

- Another way to look at retirement savings is to consider it against income earned while working. Called the "replacement rate," the numbers haven't changed considerably here either. Although incomes rose over this time period, replacement rates were about the same in 2010 as they were in 1992.

These findings are in line with what we’d expect through this transition. The transition away from DB plans was and will not be without some bumps, but DC plans are improving over time, including for low-income and low-education workers. This includes establishing 401(k) plans with auto-enrollment and auto-escalation of default contribution rates, as well as expanding coverage options to individuals without an employer-provided plan. And while some may argue that those without a college degree were better served by a defined benefit plan, data out of the Social Security Association says otherwise.

As careers spent with a single employer become more and more rare, our changing workforce needs retirement plans that can move with them. The transition to portable DC plans hasn’t always been pretty, but those plans are improving over time and expanding to provide workers with sufficient retirement benefits.

The following is a guest post from Martin F. Lueken, Ph.D., the director of fiscal policy and analysis for EdChoice, formerly the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice.

Like most states, Nevada faces challenges with rising pension costs. According to University of Arkansas economist Robert Costrell, per-pupil school pension costs have doubled nationally in the last 10 years. This trend is similar in Nevada. The contribution rate for school districts has increased by about 40 percent since 2002. Annual payments (adjusted for inflation) devoted to paying off the state’s pension debt, however, more than doubled from $540 to $1,200 per student. Unfortunately, there’s no sign of when this trend will break in the future absent structural reform.

Last year, Nevada passed the nation’s first universal education savings account (ESA) program (the state’s Supreme Court is currently reviewing the constitutionality of the law). In addition to the non-fiscal benefits attached to educational choice, the program can relieve pressure for district budgets from rising pension costs (for each one million dollars spent on the program, I estimated that the state would save almost half of that amount, while school districts would save almost $700,000). These savings would give district officials flexibility and more control over their budgets. One option they have would be to reallocate these savings to shore up retirement-related obligations.

Nevada’s effort to provide true and meaningful educational choices to its citizens by enacting the ESA program is needed. But to maximize the program’s effectiveness, it’s important for Nevada to have the right policies in place to allow its education system to fire on all cylinders. This includes a fluid educational labor market where teachers can move from one sector to another in response to changes in supply and demand. One area with potential to create inefficiencies in its teacher labor market is pensions.

In this post, I examine in detail how Nevada’s pension plan for teachers operates and show how it incentivizes teachers to make employment decisions around arbitrary points in their careers.

How Nevada’s Pension Plan Works

Public school teachers in Nevada automatically become members of the Public Employees’ Retirement System (PERS) of Nevada. The pension plan is a traditional (or “final salary”) defined benefit (DB) plan. Teachers can vest in the plan after five years, meaning that they become eligible to receive a pension. If a teacher leaves the system before vesting, she may only take a refund of her own contributions. Vested teachers can collect a normal pension starting at age 65. Teachers who leave with 10 years of service can start collecting a pension at age 62, and teachers with 30 years of service can begin collecting a pension immediately. Vested teachers can also receive a reduced benefit if they retire before age 65. Depending on a teacher’s years of service, his benefits are reduced by 4 percent to 6 percent each year younger than his normal retirement age.

The value of a teacher’s benefit is determined by how many years she works, the average of her highest three consecutive years of salary (final average salary, or FAS) and an accrual factor of 2.5 percent.

Let’s start with an example. A teacher who started at age 25, worked in the system for 29 years, and has an FAS of $50,000 can expect to receive an annuity worth:

(2.5 percent) x (29 years) x ($50,000) = $36,250 per year

While she would leave at age 54, she cannot start collecting her benefit until age 62. If she lives until age 80, then she would collect 18 years’ worth of pension payments, and the total value of her pension would be $652,500 (ignoring factors like inflation and cost-of-living adjustments).

Now consider the same teacher, but this time she works an additional year to reach her 30th year of service. Her annual benefit would be worth $37,500. While similar to the annual benefit she’d receive if she left after 29 years, she would be eligible to immediately collect a pension starting at age 55. This is a huge difference. The value of her pension would be $937,500. This large jump (44 percent) in the value of her pension benefit occurs because she would collect 25 years worth of pension payments, up from 18. By working just one additional year and reaching her 30th year of service, she can receive 7 additional years worth of pension payments.

What a difference a year makes!

The teacher in the first example has a very strong incentive to stay until her 30th year. With such a strong incentive built in to the system, however, some teachers will likely stay regardless of their life circumstances or preferences. Those who cannot remain for an additional year will consequently face a severe financial penalty for their mobility – not staying for her 30th year means the teacher in our example gives up $285,000 worth of pension payments.

The story doesn’t stop there, though. Let’s consider an additional year of work. By working her 31st year, her annual benefit would be worth $38,750 – an increase in the annual benefit of $1,250. But the total value of her retirement would actually decrease from $937,500 to $930,000, because by working an additional year, she is giving up one year’s worth of pension payments. That is, she will now collect pension payments for 24 years instead of for 25 years. In other words, the year of pension payments she foregoes is greater than the additional pension benefit she accrues from working an extra year. Financially, she would be better off retiring instead of continuing to teach in the system.

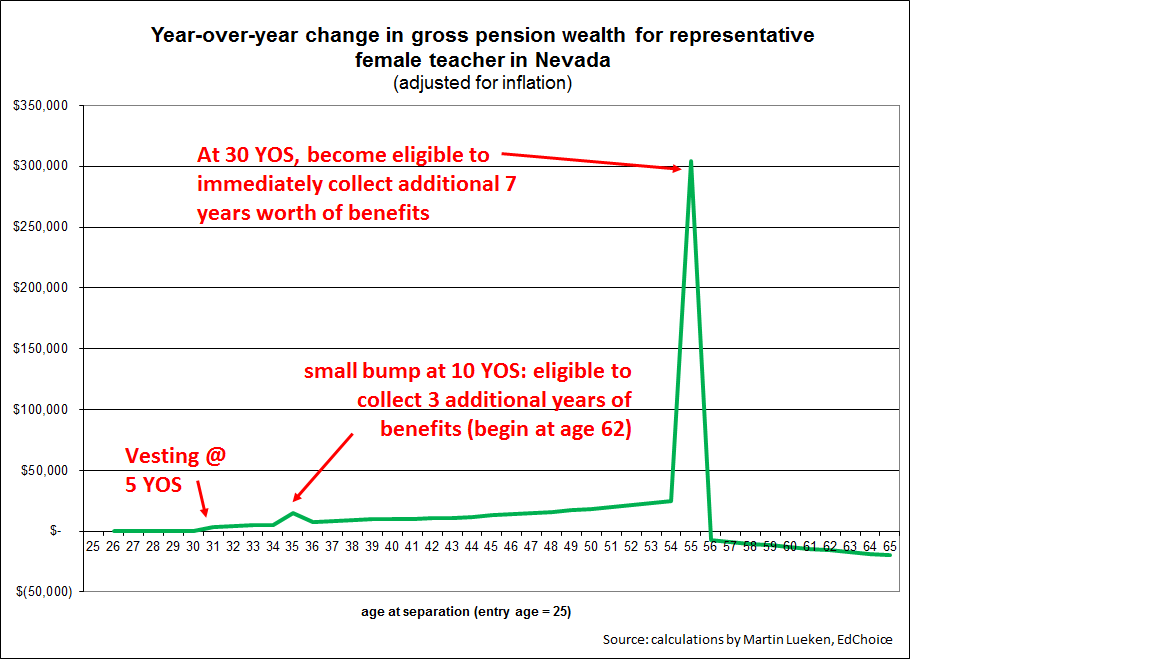

The adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” rings particularly true for examining pension incentives. The graph below clearly shows the financial incentives Nevada’s pension system places on teachers.* It plots the year-over-year change in pension wealth for a teacher who begins teaching in Nevada at age 25. This example uses the pay schedule for the Carson City School district.

Imagine that a teacher receives a one-time lump-sum payment worth his pension wealth when she retires in a given year. This amount (i.e. the value of his pension wealth) varies with the timing of her decision to leave covered service. For each year in his career which she might leave, the value on the graph at a given point is how much the value of her retirement benefit changes from working an additional year. It is not the value of her pension wealth itself.

Before vesting, she is not eligible to receive a pension. Her gross pension wealth is zero (and therefore the change from year-to-year during this period is zero). If she leaves in year five (when he is 31), she can collect a pension starting at age 65 because she will then be vested in the system. Her pension wealth at this point would be worth $3,671.

The value of her retirement grows slowly and steadily up to age 54, at which point she’s given 29 years of service to the state. Working his 29th year generates an additional $24,586 in pension wealth. She can collect a pension starting at age 62 if she leaves Nevada’s system at this point. Her total pension wealth is worth almost $400,000 (not shown in the graph).

If she works year 30, then she will increase her pension wealth by $304,288 for this single year of service. This will boost her total pension wealth up to more than $700,000. In terms of her retirement, this would be an extraordinary year in his career.

If she works another year, then her pension wealth will actually decrease by $7,411. Financially, she’ll be better off retiring after his 30th year instead of continuing to teach. Of course, numerous factors drive these decisions (health, family circumstances, etc.). But it’s not hard to imagine how this financial incentive can become a serious consideration that is difficult for a teacher to ignore—if it wasn’t a main consideration for an individual before. Workers in general are very responsive to these incentives.

The key question is: What is so special about the points where these spikes occur?

There is no logical answer to this question; it is an artifact of an outdated retirement system designed long ago for a different kind of work force. And there is evidence that it might not serve the purpose that the plan was intentionally designed to serve. According to a report by Bellwether Education Partners, just over half of teachers in Nevada (55.3 percent) vest, and only 28.7 percent of Nevada teachers stay until normal retirement age. Like most other plans that cover teachers, Nevada’s plan rewards just a small minority of teachers who stay long enough to reach retirement eligibility.

Incentives for teachers in Nevada’s pension plan

The behavior of Nevada’s pension plan is typical of most other FAS DB plans, in that it backloads pension benefits. The example above demonstrates how two forces at play in these plans work to create inefficiencies in the teacher labor market. Parameters in the plan work to “pull” teachers already in the system to remain until arbitrary points in their careers, and “push” teachers out after these points—regardless of their life circumstances, passion or dispassion for teaching and other job conditions.

First, strong incentives work as a “pull” to incentivize teachers to continue teaching while covered by the system up to the spike. That is, these factors incentivize teachers who might otherwise separate from covered service to “hang on,” regardless of whether they want to (perhaps they are no longer suitable for the job or burned out). Second, teachers face strong incentives to retire early. The period after the spike serves as a “push” to incentivize teachers to leave teaching after 30 years, regardless of whether they have good years left to give or whether they desire to continue teaching. Such plan designs are arbitrary and drive a wedge into the teacher labor market.

This is not ideal for Nevada’s teacher labor market, which supplies public schools (including charter schools, which are required to participate in NVPERS) and private schools. Consider that Nevada’s system, like many similarly structured DB plans offered to most public school teachers throughout the country, is structured to:

- create a disincentive for teachers to switch between public and private schools;

- create a disincentive for potentially effective short-term teachers from entering teaching;

- create an incentive for effective teachers to retire early even though they may still have good years to offer;

- create an incentive for less-effective teachers to enter the profession in place of those who were enticed not to enter;

- retain some teachers longer than optimal, regardless of effectiveness; and

- encourage teachers to enter and stay in administration to spike their final salary, regardless of whether they are suitable for such positions.

Implications for Nevada’s K-12 schools and policy recommendations

Last year, Nevada passed the largest ESA program in the country with the goal of expanding educational options for all Nevada families. To achieve this goal, the state will need to attract high-quality schooling options and the staff to run them. It will need to ensure that policies are conducive to attracting and retaining a high-quality and responsive teaching workforce. As it stands, the underlying incentives in its pension plan runs counter to this goal.

Put simply, the system is not designed to serve all teachers. It penalizes teachers who leave before reaching retirement eligibility, regardless of an individual’s life circumstances.

Nevada could alleviate this potential problem by offering teachers more choices in the kinds of retirement plans offered. Given the idiosyncratic incentives embedded in its current retirement plan—and because it imposes mobility costs on mobile teachers—the state should at least offer a defined contribution (DC) plan as a choice for its employees. Not only might mobile teachers have stronger preferences for them, but some teachers may also not know with certainty whether they will work in the system for an entire career. The portability that comes with a DC plan would be a welcome option for some teachers.

In addition, because benefits are tied directly to contributions, the system is much less likely to accrue large unfunded liabilities.

Nevada’s pension debt is the equivalent of $27,750 per student.

Alternatively, the state could increase the portability of its current plan by allowing refund claimants access to employer contributions. Under the current plan, teachers who leave prior to retirement eligibility and opt for a refund receive only their contributions (currently 12.25 percent of creditable earnings) plus interest. Employees under NVPERS do not enroll in Social Security, however, as many other states do. Given that some financial experts usually recommend savings rates of about 15 percent to 20 percent for retirement security, teachers who take a refund may be under-saving. Allowing access to even a portion of the employer’s contributions (about 13 percent in FY 2014) could help teachers meet this target. Although this option addresses portability, it would not improve funding and sustainability problems.

Rising costs and arbitrary incentives are just two reasons for Nevada to pursue pension reform. In light of its bold step to enact a universal ESA program fit for the future, its pension plan remains in the past.

*The graph is based on a measure which economists Robert Costrell and Michael Podgursky coined “pension wealth.” It can be computed for any year that a teacher leaves service (and the system). Pension wealth is the present discounted value of the stream of pension payments she can receive, discounted for survival probabilities. It is a lump sum. Present discounted value converts dollars given for future points in time into today’s dollars. I also adjust all figures for inflation. I assume nominal interest is 5 percent and inflation is 2.5 percent.

Education funding is hard to come by these days. Most states still haven’t raised their school funding to the pre-recession levels. In Illinois, for example, the Chicago Public School system is almost bankrupt. Earlier this year in Michigan, Detroit teachers staged a “sick-out” to protest the deplorable conditions in their schools.

But, the grass is much greener in Maryland. For the second year in a row, they have a surplus of state funds. Included in the surplus, the state legislature allocated around $20 million to help counties fund their teacher pension systems.

But, Governor Larry Hogan won’t release the money.

Hogan argues that he is withholding the funds because the money is tied to “good and bad things,” and since it was a package deal, he chose to fund none of them. Understandably, teachers are upset and accuse the Governor of cutting the education budget.

Governor Hogan disputes this claim and points out that his administration has raised the state’s K-12 budget to record levels, even without the additional funds. While it is true that Maryland’s total spending on K-12 education is up, districts still did not receive the full amount of money allowed by the state funding formula. Therefore it becomes clear that withholding the additional funds set aside by the legislature to help counties pay their teachers’ pensions only adds to the problem. Moody’s credit rating service warned that the decision could adversely affect the counties’ bond ratings.

This fight over teacher pension funding raises an important philosophical question: Does money spent on teacher retirement count as education funding?

The answer is yes.

If states and districts consider funding teacher retirements as separate from their investments in K-12 education, it becomes much easier for legislators and governors to kick the funding liabilities down the road and leave them for others to sort out. It also creates the odd situation like the one we see in Maryland in which the state is both raising and cutting education funding. This happens because the state increased its allocations to districts, but those districts will be required to come up with a larger share of the funding for their pension funds. In other words, Maryland is robbing Peter, the county pension funds, to pay Paul, the state funding formula.

There are a few key reasons why teacher pension spending is education spending and should be recognized as such:

First and foremost, a pension is part of the deal that states and districts made with teachers: less money in salary in exchange for a healthy and sustainable retirement. In other words, pensions should be thought of as part and parcel of teacher compensation. With that in mind, pensions are certainly education spending.

Even though, as my colleagues have pointed out, pensions are not an effective way for the majority of today’s teachers to save for retirement, that isn’t an acceptable reason to retreat on existing pension obligations that current teachers rely on and need in their retirement. States may want to consider offering alternative retirement plans for new teacher to better meet their needs since only around half of teachers leave the profession with a pension. Furthermore, this would help states avoid adding to their existing pension liabilities. While such a change would not erase a state’s current obligation, it would help to make sure that the problem doesn’t grow.

Regardless of the model chosen, spending on teacher retirement should be counted as education funding since such investment cannot be extracted from the state’s general K-12 budget. This is because – as is the case with Maryland right now – each jurisdiction will need to make up for that lack of pension funding. To do that, districts either need to raise additional tax revenue, which will disproportionately burden low-income communities, or they will need to cut back on other education expenditures. The third option would be to ignore their pension liabilities altogether. But, that approach can be disastrous, just ask Illinois or New Jersey. Finally, thinking of funding for teacher pensions as education spending will force policymakers and the broader public to reckon with the fact that teacher retirements spending is extremely high, rising, and cutting into the available funds for teacher salaries.

For many governors and state legislators, funding pensions can seem politically challenging. It’s not a sexy topic, either. And for some constituents, it can seem less relevant to education than more direct budget items, such as new books or a computer lab. Nevertheless, investing in teacher retirement and in schools are intertwined. Thus, resolving the impending pension crisis in many ways in not only integral to school funding writ large, it is fundamental to high quality schools.

Taxonomy: