Advocates of teacher pension plans claim that pensions help retain teachers in the profession. That is, they argue that the very structure of defined benefit pension plans encourages workers to stick around and devote their lives to the profession.*

The problem is, researchers can't find much evidence this is true. For example, when St. Louis spent $166 million to enhance the retirement benefits it offered to teachers, it saw a temporary, one-year boost in retention among teachers already eligible for retirement. But all other groups of teachers acted as if nothing had changed; after all that money, they were no more or less likely to leave St. Louis schools. Similarly, state plans themselves do not assume that qualifying for a pension has an effect on teacher retention. If pensions were really a retention incentive for workers, we'd see evidence of teachers hanging on just long enough to qualify for a pension. We don't.

The latest piece of evidence on this question comes from a BLS Working Paper on Oregon. Prior to 1996, Oregon offered its teachers what the authors call "one of the most generous pension plans ever devised." The state had two formulas, and upon retirement Oregon teachers automatically received the better of the two. The first was a traditional defined benefit pension plan awarded by formula, and the second was a "money match" pension plan that gave teachers an amazing investment promise. In good years, teachers received the actual market return (minus a small fee), and in bad years teachers were guaranteed at least an 8 percent return. The state offered unlimited upside while shielding teachers from any potential losses.

This was an incredible deal, and eventually Oregon legislators realized they couldn't afford it. They subsequently enacted retirement plans for new teachers that were worth half to one-third as much as was given to those hired before 1996.

This provided an excellent real-life experiment to test the theory of pension advocates. If they were right, Oregon's pension cuts should have led to a mass exodus of teachers. Oregon went from having one of the most generous retirement plans ever created to a run-of-the-mill plan equivalent to what the typical state offered. Teachers hired after 1996 had much less reason to stick around, so theory would predict they'd have higher turnover rates.

That's not what happened. Despite having much less generous retirement plans, retention rates for early- and mid-career teachers didn't change at all. For late-career teachers, turnover actually fell. Regardless of plan type or teacher experience level, Oregon's teacher turnover rates looked pretty much identical to those in nieghboring Washington State. The authors concluded that, "Oregon’s policymakers and citizens allocated substantial resources to its retirement system and, in return, received little economic benefit in the form of promoting longer teacher tenures."

What was going on here?

The authors suggest opacity as one major driver. Oregon teachers received annual statements on the value of their traditional defined benefit formula, but they never saw estimates of the value of their money match formula. Only when they neared retirement did they see the full value of the state's money match promise. That "windfall" may have pushed teachers to retire earlier than they otherwise would have.

The opacity argument may explain part of Oregon's extreme situation, but it doesn't explain results like the one in St. Louis, or what we see in state pension plan assumptions around vesting periods. Another explanation is simply that teachers, like most humans, are not that worried about retirement until they get close to retirement age. That's what was happening in St. Louis, and a forthcoming paper on the state of Missouri suggests a similar pattern. Teachers just aren't that sensitive to retirement plans until very, very late in their careers. That would also explain why teachers seem to retire based on when the retirement plan nudges them to do so.

In short, the best way to characterize the research literature thus far is that pensions don't enhance teacher retention. In fact, because traditional pension plans push out veteran teachers, and because those veterans tend to be better than their replacements, pension plans are actively harming overall teacher quality. Contrary to the theories of pension plan advocates, shifting to alternative retirement plans that didn't push out veteran teachers would be better for students.

*Pensions could also be serving as a recruitment incentive by attracting certain types of people to the teaching profession. That's possible, but half of all new teachers won't qualify for any pension at all, and 80 percent won't stay long enough to reach the full normal retirement age. The back-loaded nature of pensions may be deterring some otherwise talented people who would prefer to receive upfront compensation rather than waiting 20 or 30 years for the promise of a lucrative retirement benefit.

The Wall Street Journal had a big front-page story yesterday on how American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten uses teacher pension plans to blackball disfavored Wall Street hedge fund managers. It illustrates a few interesting issues that go against the conventional wisdom about teachers, their unions, and their pension plans:

- With $1 trillion in plan assets, teacher retirement plans have real clout with Wall Street hedge funds. In turn, the unions that staff the boards deciding how to invest that money also have clout. The Journal story gives several examples of times when high-profile Wall Street hedge fund managers responded to Weingarten's calls by changing their private philanthropic giving or even resigning from a nonprofit's board.

- As the story makes clear, public pension plans are huge investors in private equity and hedge funds. What's going on here is Weingarten expressing her preference for certain hedge funds that will kowtow to her political demands; it's not about opposition to all hedge funds.

- This political favoritism raises the question of whether pension plans owe a responsibility to their members and taxpayers to seek out the best return on their investments, regardless of politics. After all, if plan investments suffer, it will be future workers and taxpayers who must fill in the gaps.

- It also raises the question of why teacher pension plans are invested in hedge funds at all. There's compelling evidence to suggest pension plans would be better off making passive investments that track the broader market rather than trying to pick the right investment manager to make the right investments. Investing in hedge funds and private equity also means teachers are indirectly investing in all sorts of odd things. My personal anecdote on this comes from an office building in Rosslyn, Virginia that I occasionally pass on my commute. On a sign outside the building, it proudly proclaims its investors, including the State Teachers Retirement System of Ohio. Do Ohio teachers know they are investing their retirement savings in a skyscraper in Rosslyn, Virginia? They are.

- As I work to raise awareness about teacher pensions, I'm often accused of being a shill for Wall Street and "1 percenters." This is almost exactly backwards. Wall Street as a whole does pretty well under the current arrangement, because they only have to deal with a few union power brokers in order to access a huge market. If states offered teachers individual retirement accounts, each teacher would make her own investment decisions. And, if states structured those plans wisely, the investments would be concentrated in low-fee mutual funds. In an ironic twist, reforming teacher pension plans would help companies like Vanguard that offer cheap, mass-market index funds, and it would seriously harm hedge funds and private equity firms. Unions don't want to admit this, of course, because that transition would diminish their political clout on Wall Street.

Taxonomy:Last month we released “The Pension Pac-Man: How Pension Debt Eats Away at Teacher Salaries,”which used data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics to show that, like the proverbial Pac-Man, the rapidly rising costs of teacher retirement and insurance benefits are gobbling up funds that could be spent on salaries. The BLS released new data for 2016 last week, and the trends are all in the wrong direction:

- Since 1994, teacher salaries have not kept up with inflation, but total teacher compensation has. That’s because benefit costs are rising much faster than inflation and eating up larger and larger shares of teacher compensation. As a share of total compensation, teacher salaries have never been lower. For the average teacher, their salary is only 68.8 percent of their total compensation; benefits consume the remainder.

- Thanks in part to the Affordable Care Act, insurance costs have finally begun to moderate for all workers, including teachers. Retirement costs have not.

- Teacher retirement costs hit new all-time highs in 2016, in both dollar terms and as a percentage of teacher compensation.

- Retirement costs tend to be higher in the public sector, but retirement costs for teachers remain much higher than for any other profession, including other public-sector workers. While the average civilian employee receives $1.74 for retirement benefits per hour of work, public school teachers receive $6.67 per hour in retirement compensation. As a percentage of their total compensation package, teacher retirement benefits eat up more than twice as much as other workers (10.9 versus 5.1 percent).

As I note in our full report, teachers won't ever see most of this money. It's money that must be used to pay down unfunded pension liabilities, not actual retirement benefits. On average, for every $10 states and districts contribute toward teacher retirement, $7 goes toward paying down past pension debt, and only $3 goes toward benefits for current teachers. Without a change, teachers will continue see the Pension Pac-Man eat further and further into their take-home pay.

Taxonomy:On Friday, The New York Times ran a story called "Higher Education in Illinois Is Dying" and cited rising pension costs as a major factor in the state's budget woes. Similarly, in our recent report on pensions in the state of Illinois, we noted Illinois taxpayers are now contributing more toward teacher pensions alone than for all of the state's public colleges and universities combined.

Unfortunately, Illinois is not alone. Like the insatiable Pac-Man, pensions are eating further and further into state and local education budgets, eating up dollars that could be spent on lots of other things. That's true for all public services, but higher education is uniquely harmed by rising pension costs.

To get a sense of where this is happening, I collected data on state and local contributions toward employee retirement plans from the Boston College Center for Retirement Research. To count total retirement spending, I included all state and local contributions, because some states require cities or school districts to make the majority of retirement plan contributions, while others handle it all at the state level. (Not all of the plans are traditional defined benefit pension plans, but most are. Contributions to defined benefit pensions are also more volatile than contributions to defined contribution plans, and they're the ones driving up state and local retirement plan costs. Update: To be clear, these plans include teachers and non-teachers alike. This calculation is meant to count all state and local spending on retirement costs.) The data do not include all local plans, but they do capture most of the largest local retirement plans. If anything, this method is likely under-counting total retirement spending. Next, I collected data on each state's total higher education spending (public and private) from the National Association of State Budget Officers. To get a sense of state spending on today's college students, I excluded expenditures on bonds and contributions from federal funds. Both sets of data are for Fiscal Year 2014.

By comparing these two data sources, I found 10 states where retirement costs are higher than higher education spending--California, Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Oregon, and Pennsylvania (see map below).

In general, these 10 states tend to have a few things in common. Most fall near the bottom of the list in terms of responsibly funding their pension plans. Some states on the list don't spend that much money on their higher education systems. Several of the states have flat, aging population bases. Most are traditionally "blue" political states where voters are presumably more likely to value government spending on social services.

What to make of this finding? That depends on your perspective, but over time, I suspect higher education budgets will continue to be squeezed in favor of pensions. On the retirement side, costs will likely continue to rise. Even amidst one of the longest and strongest bull markets in history, pension plans still haven't recovered, and if pension plans fail to hit their 8 percent investment targets every year, they will need taxpayers to continue bailing them out. Higher education will be one of the primary losers from this arrangement. That's because higher education is unique from other public services in a few ways:

- No state constitutional protections. Higher education typically does not have the same constitutional protections as K-12 education does. Whereas advocates can and do take to the courts for adequate state funding in the K-12 sector, there's no such parallel in higher education.

- The ability to raise prices. In higher education, the students themselves are asked to pay a share of their educational expenses. Over time, the share that students are asked to pay has risen as states turn to tuition increases to address budget deficits.

- Lack of federal incentives. In other budget areas, including K-12, Medicaid, transportation, and a host of other social service programs, states lose out on matching federal dollars when they cut funding. In contrast, there's no meaningful lower-bound for higher education, and in fact the federal government picks up much of the tab when states cut higher education funding.

To get in front of one common misconception, this situation is not merely a natural consequence of changing demographics. Unlike Social Security, where current workers pay for current retirees, defined benefit pension plans are supposed to be pre-funded. That is, pension plans were supposed to put away enough money in each successive year such that they'd be able to afford benefit payments down the road. Over time, through a combination of poor funding practices and unstable investment returns, pension plans have failed to live up to that promise.

Finally, regardless of how much meaning we attach to this comparison, it's a prime example of how pensions are serving as an inter-generational transfer of wealth. This is true for individual teachers--states have cut benefits for new teachers so much that new teachers starting today will never get benefits worth as much as the amount of money that goes into their pension plan--and it's true for all other citizens as well. If state and local governments are required to pour money into pension debts, that's money they won't have available to support other government services, including higher education. One under-appeciated consequence of this arrangement is that college students are being asked to pay higher tuition bills at least in part due to growing pension obligations.

The pension obligations are not going away anytime soon, and there's no magic solution for paying down those past debts. But the sooner states realize that their volatile defined benefit retirement plans are harming all other areas of government, the sooner they can start looking for better models.

Taxonomy:Portability is a key issue in the pension debate. But what exactly does this mean?

Portability is the ability for an individual to take their contributions and investments with them wherever they may go, whether across state lines, organizations, or sectors.

Traditional pension benefits aren’t portable. When a teacher moves to a new state, her previous service years don’t automatically rollover for free. Instead, she starts back at zero.

Moreover, once a teacher leaves the state retirement system, her pension benefit stops growing. A teacher’s pension is a fixed, defined future benefit, and bears no direct relation to a teacher’s employee contributions. This amount is locked and she cannot continue to grow it once she leaves the system. Whether the market booms or plummets, the teacher will get the same pension benefit at retirement.

For example, consider a 25-year-old teacher who teaches for 15 years and then moves to another state at age 40. Her pension is calculated based on her final salary when she leaves; this amount remains fixed. But she cannot collect this benefit right away. Instead, she has to wait another decade or two until she reaches the plan’s predetermined normal retirement age—usually around age 60 to 65.

And that creates a problematic time gap. The teacher’s already meager pension benefit is not growing and is instead eroding away with inflation. Most states will add cost-of-living adjustments once she begins collecting her pension, but not before then. In the meantime, she could have been investing this money elsewhere and would likely come out with better gains if she had conservatively invested on her own.

What makes portability so critical, then, is it allows workers flexibility without these penalties. Teachers who move can “buy” service credits that count toward their new pension; but, this can end up being costly and won't necessarily make up for lost years. In the private sector, workers can continue to invest and grow their contributions until they officially retire, regardless of whether they move across companies or state lines. Teachers, as one of the largest class of workers with a college degree, should be afforded this flexibility also.

Note: Under this system, second-career teachers who begin teaching at older ages are actually better off because there isn’t as much lag time between the time they leave and when they retire.

Taxonomy:Despite the conventional wisdom, there’s very little evidence that current education policies are driving teacher turnover. In fact, although the teacher turnover* rate rose in the 1990s and 2000s, more recently it's started to fall. This change can be traced to changing demographics of the teacher workforce as a whole.

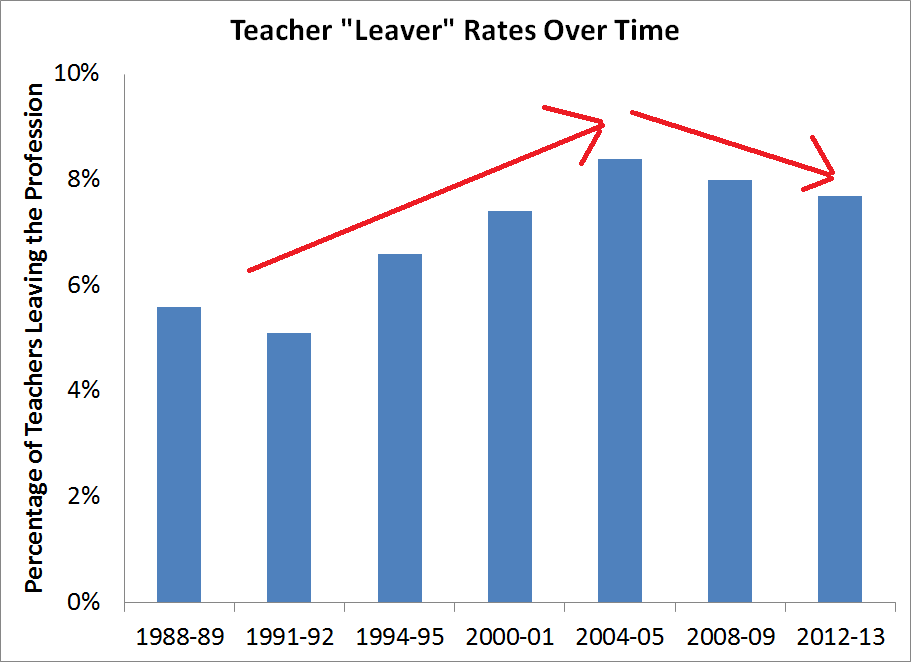

To understand how these trends are shaping the teacher workforce, let's start with the overall national data. The graph below comes from a post I wrote last fall showing national, longitudinal data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). It tracks the percentage of teachers in a given year who leave the profession. As the arrows show, there was a general upward trend through most of the 1990s and 2000s, but that trend has reversed in more recent years:

What was behind the rise in teacher turnover in the first place? It can't be blamed on policy changes like No Child Left Behind (NCLB) or Common Core or teacher evaluations, because the upward trend predates all of these policies. The conventional wisdom on NCLB in particular is contrary to what the evidence actually says. But what about more vague concepts like "respect" for teachers? That's harder to pin down, but there's no evidence there was ever some sort of golden era where America teachers received the respect or pay they deserved.

The simpler, more plausible explanations for the changes go back to human nature and demographics. After all, teachers are human, and they tend to behave like all other workers. Turnover tends to rise during economic expansions, when employers are hiring, and it falls during recessions, when hiring dries up. Worker life cycles matter as well. Inexperienced workers, including teachers, tend to have higher turnover rates, and so do older workers approaching retirement. All else equal, a less experienced, older workforce is likely to have higher turnover rates overall, even if retention rates for particular groups of workers stay exactly the same.

The teacher workforce has changed in exactly these ways. As Richard Ingersoll has documented, today’s teaching workforce is both “greener” and “grayer” than it was in the past. That is, the teacher workforce became both older and less-experienced than it had been. These alone are conditions that would cause overall turnover rates to rise.

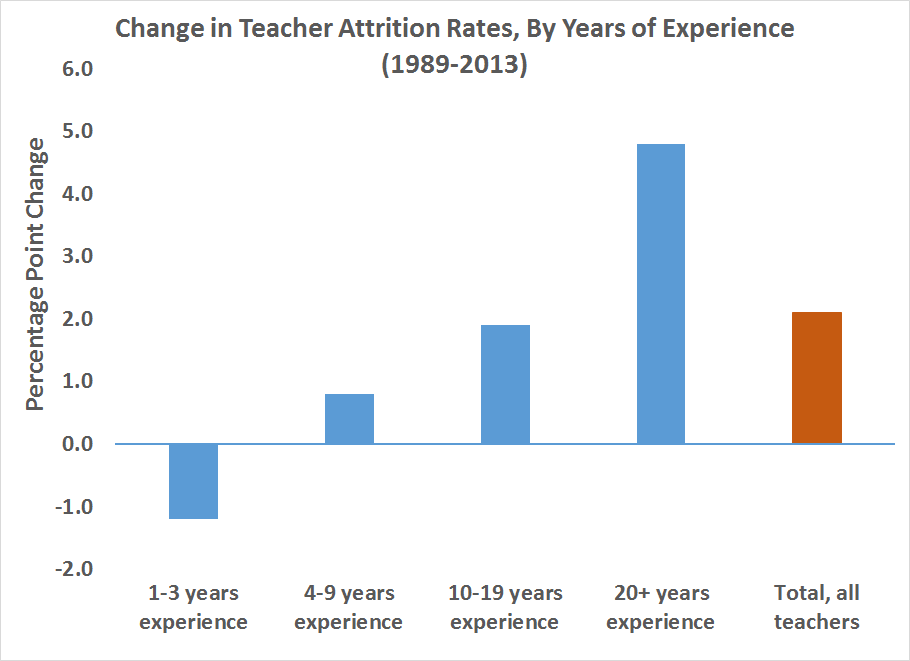

But there's even more going on underneath those broader trends. Turnover rates for inexperienced teachers have been falling, not rising, while turnover has risen among more experienced teachers. The graph below shows the change in turnover rates from 1987 to 2012 by years of experience. The turnover rate for teachers with 1-3 years of experience fell by 1.2 percentage points during this period, whereas the rate among teachers with 20 or more years of experience increased by 4.8 percentage points.

In terms of annual turnover rates, teachers with 20 or more years of experience are now the most likely group of teachers to leave. From 1987 to 2012, the turnover rate for this group rose from 6.6 to 11.4 percent, compared to the overall change for all teachers from 5.6 to 7.7 percent.

Most of this is due to retirement, because similar turnover patterns emerge when looking at teacher age. Over the last 15 years, the only age group of teachers with rising turnover rates is those over the age of 50. In its regular teacher surveys, NCES asks departing teachers why they are leaving the profession, and the percentage of those teachers identifying retirement as their next destination has risen from 24.8 percent in 1988-9 to 38.3 percent in 2012-13.

This reflects both an aging teacher workforce and a reduction in the age at which teachers can retire. As Ingersoll notes, our teacher workforce was “graying” for most of the last 25 years, driven both by existing teachers aging into the profession and an increase in the hiring of older “new” teachers. A large group of older career-switchers entered teaching in the late 1980s, and the result is the chart below. It comes from Ingersoll’s report, and it shows the percentage of teachers who are age 50 or older (the chart includes public and private teachers, but private school teachers tend to be much younger, so a similar chart for public school teachers only would likely be even higher). As the chart suggests, we already passed a peak in the “graying” trend, which may be one reason overall turnover rates have started to fall.

It’s also no coincidence that the “graying” of the teacher workforce roughly corresponds with the rise of the Baby Boom generation. It shouldn’t be a total surprise that we’d see large numbers of teacher retirements as this generation ages out of the teaching workforce. (If you want to see this visually, check out these graphics from my colleague Leslie Kan on changes in Illinois’ teacher workforce. The retirement of a large cohort of veteran teachers is clearly visible in the graphs.)

This period also coincides with states lowering their retirement ages. From the 1980's to the early 2000s, the median state lowered its retirement age for teachers from 58 to 55. Veteran teachers have invested nearly a full career in teaching, and teacher pension benefits tend to increase steeply as teachers approach retirement age. Evidence from California and Missouri suggests teachers know about these late-career pension incentives and act accordingly.

So while it may be tempting to blame teacher turnover on current education policies, demographics and rising retirement rates offer a more plausible explanation.

*Throughout the post I refer to "teacher turnover" as the percentage of teachers who leave the profession in a given year. This is what NCES calls the "leaver" rate. Another group of teachers move between schools. That churn certainly has a real effect on schools, but what I'm interested here is teachers who actually leave the profession altogether.

Taxonomy: