Teach for America celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. An increasing number of alumni are staying in the classroom, and the organization has adopted new policies to recognize this.

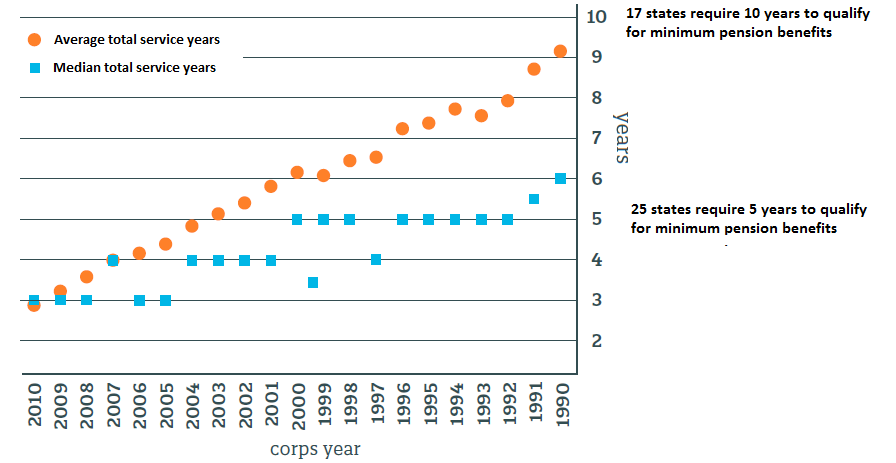

Teach for America alumni stay in the profession longer than commonly thought, and those rates are increasing over time. A recent TFA report found that retention rates have increased significantly over time. For example, the percentage of teachers who reported teaching a total of 5 years increased from just 3 percent of the 1990 corps to 23 percent of the 2009 corps. The graph below show the average and median total service years for each TFA cohort from 1990 to 2010. Each set of dots represents corps members beginning in that year.

Source: Raegen Miller and Rachel Perera, “Unsung Teaching,” Teach for America, 2015. Note: n=23,653. Teach for America reports having a 70 percent survey response rate.

State policies, however, still remain out of sync with the needs of teachers—both for Teach for America alumni and the teaching workforce as a whole. In response to massive underfunding, states have passed stricter policies that make it more difficult for new teachers to gain access to adequate retirement benefits. Nationally, the average state now requires teachers to stay at least six years before qualifying for any retirement benefit at all. Forty-five states and the District of Columbia require 5 years or more, and 21 states require 7-10 years. Only five states have a minimum service requirement of four years or less.

So while more teachers are teaching for longer, the majority of teachers still won’t meet qualify for retirement benefits. For TFA teachers, high mobility means that not all of them necessarily taught successive years or stayed in one place; teachers may move across state lines to teach in a different school within their charter network, return to their home state, and/or take a break to raise a family.

But even for teachers who do vest, the odds are stacked against them. Not all pensions are equal, and having some pension doesn’t guarantee it will be a good one. In the median state, teachers need to teach for a minimum of 25 years before “breaking even,” the point where their pensions are finally worth more than their own contributions. Five out of the six original Teach for America regions have break even points of 20 years or more. This means that a teacher who taught in the original 1990 corps--and remained teaching in the same state for the past two decades--will finally be breaking even. Any corps member who doesn’t stay that long will lose out.

In response to these issues, Teach for America has recently taken a bold stance on teacher compensation and retirement benefits, stating:

“Teachers not only need to make competitive salaries, but we need to change compensation structures to reflect modern workplace realities. In particular, in many states, too much of a teacher’s total compensation depends on spending a long time, decades in some cases, in the same school system…Pensions need to be more portable, reflecting the reality that many teachers will not be able, or sometimes willing, to stay in the same place for the duration of their careers.”

Over 11,000 Teach for America alumni remain teaching in the classroom. While they make up only a small fraction of all teachers nationwide, teacher mobility represents a trend in the overall workforce (note: TFA is simply too small to be a significant factor of these national trend).

Teachers are one of the largest class of professionals and need adequate retirement benefits and compensation. It’s time for states to start fostering policies that reflect that.

Note: I was a former Teach for America corps member and taught in Baltimore for three years.

Taxonomy:President Obama struck at the heart of retirement issues in his final State of the Union address: workers need portable benefits.

This may have been the first time a retirement issue was quoted as one of the best lines from the President’s speech:

“ We also need benefits and protections that provide a basic measure of security. After all, it's not much of a stretch to say that some of the only people in America who are going to work the same job, in the same place, with a health and retirement package, for 30 years, are sitting in this chamber. For everyone else, especially folks in their forties and fifties, saving for retirement or bouncing back from job loss has gotten a lot tougher. Americans understand that at some point in their careers, they may have to retool and retrain. But they shouldn't lose what they've already worked so hard to build…And for Americans short of retirement, basic benefits should be just as mobile as everything else is today.”

President Obama is correct that few workers will stay 30 plus years in one given position and place. And to assume otherwise is almost unreasonable, or at least, highly improbable. The median U.S. worker has less than five years of experience at his or her current job according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And teachers are no exception.

Teachers, like the rest of the American workforce, have become increasingly mobile over the decades. If you asked a teacher how many years of experience he or she had two decades ago, the most common answer would have been fourteen or fifteen years. The most common year of experience is now 5 years.

Yet, state pension systems treat teachers as if they were a static workforce. A teacher can’t easily transfer her benefits from one state system to another without paying a high price. To receive full benefits, teachers need to do exactly what Obama pointed out as highly improbable: work the same job, in the same place, for 30 or more years. Social Security is a nationally portable program and alleviates this issue to a certain extent. But it’s not available to all teachers, causing problematic gaps in coverage.

Retirement policy is an area ripe for reform, and policymakers are beginning to see this. Obama supported efforts to make military pensions more portable, and he introduced the concept of a "myRA" in 2014’s State of the Union address. The myRA program, now in full swing, provides portable savings for workers who otherwise don’t have access to a 401k or other retirement plan through their employer. A growing number of states are also considering building on that model and providing similar options in their states.

While all workers don't yet have fully portable benefits, President Obama has laid the groundwork for moving the country in that direction.

Taxonomy:Earlier this week, the Supreme court heard the case, Friedrichs v. California. The case has spurred much discussion about union dues and their required base contribution, or “agency fee.” Add up all of these fees alongside pension contributions, and teachers are spending a significant portion of their salary on pensions without getting much in return.

Read my post on union dues and pensions on Fordham B. Institute’s The Flypaper.

Taxonomy:The trade publication Pensions and Investments reports that the 100 largest public pension funds lost $146 billion (5 percent) in the third quarter of 2015. Although we don't have the final year-end data yet for the plans yet, international and domestic stock markets closed 2015 essentially flat on the year. What does this mean for pensions? Three things:

- Unfunded liabilities will rise. Pension plans depend on hitting their investment assumptions. To calculate how much they need to save today in order to pay benefits in the future, pension plans must make a number of assumptions, including how fast their money will grow over time. If a pension plan assumes the market will rise 8 percent, anything below 8 percent is essentially a loss and will add to the plan's liabilities.

- Pension plans have yet to fully recover from the last recession. We're in the midst of one of the longest and strongest bull markets in modern history. And while the S&P 500 has tripled from its March 2009 lows, pension funds have barely started to recover. Part of that is due to states prudently lowering their investment assumptions--which increases the amount they must pay in the present--but state and local workers should be worried that their pension plans won't be prepared for the next recession.

- States may face more pressure on benefits. As pension liabilities rise, states become more and more likely to cut benefits, especially for new workers. Another market crash could set off another round of benefit cuts. That would not be good for teachers or other public-sector workers. Instead, we hope states tackle two problems at once and simultaneously address rising costs and inequitable benefit structures. If states do one but not the other, the cycle may be doomed to repeat itself.

While retirement may seem distant for many, retirement security became an increasingly important issue for policymakers in 2015. Here are highlights in pension-related policy news and research from this past year.

The most popular and signficant pension stories from our website in 2015:

- School pension costs have doubled. In a guest post, Robert Costrell describes how nationally, pension costs have more than doubled in the last decade, from about $500 per pupil in 2004 to over $1,000 today.

- New teachers are paying for past pension debt. A new CALDER working paper estimates that new teachers are contributing, on average, over 10 percent of their salaries to pay down their pension plan's past debt. Similarly, our report found that new teachers are bearing the brunt of post-recession cuts.

- Three-quarters of new teachers will earn less in pension benefits than they contributed. Because pensions are so heavily backloaded, teachers must work many years before their future benefits exceed the value of their required contributions. In the median state, teachers must serve at least 25 years to receive a pension worth more than their own contributions. Read The Atlantic’s coverage of our report here.

And around the country, here were our picks for some of the most important pension news stories in 2015:

- Military pension reform. President Obama signed into law a historic overhaul of the military’s pension system. Beginning in 2018, new members of the military will participate in a hybrid retirement plan. The new plan is a significant change from the previous pension plan, which required members serve at least 20 years to receive any retirement benefits. Military families, however, continue to be penalized by non-portable, state retirement plans.

- MyRA and government-sponsored retirement accounts. Over half of all private sector workers do not participate in a retirement plan. In November 2015, the federal government rolled out a low-cost retirement option called "my retirement account," or myRA. States such as Illinois and California have passed their own legislation to automatically enroll workers without an employer-sponsored retirement plan into a state-sponsored government plan.

- Illinois pension reform overturned. In Illinois, the state Supreme Court overturned a pension reform law that would have reduced benefits for current workers. A similar Chicago pension reform law was overturned by a district court and will be reviewed by the state Supreme Court in 2016. The rulings mean that state policymakers will need to rethink pension reform.

Taxonomy:Roughly half of American private sector workers don’t have a retirement savings plan at their jobs. But it’s not by choice. Eighty-four percent of these workers don’t have access to plans.

And educators aren’t immune. Only one-fifth of early childhood teachers have a retirement plan, according to the National Child Care Staffing Study. Unlike most elementary and secondary teachers, many early childhood teachers aren’t public workers and aren’t eligible to participate in their state’s teacher pension plan. (They also earn significantly less in salary.)

The federal government now offers a low-cost retirement option called, my retirement account or myRA. There’s no minimum amount and workers who don’t have a 401k or pension plan can set-up automatic deductions from their paycheck into a myRA account. Once in the account, the savings are invested in bonds backed by the U.S. Treasury. While this won’t yield high investment returns, it is a safe bet and has no fees.

One drawback, however, is that workers have to choose to sign up for myRA on their own initiative. And Americans aren’t very good at saving. Yet, empirical research, shows that automatically enrolling or nudging employees into a plan (while still allowing them to opt out) is a much more effective way to boost participation.

A growing group of states have taken the idea behind myRA one step further. States like California and Illinois have passed legislation that would automatically enroll workers without an employer-sponsored retirement plan into a state-sponsored government plan. The legal aspects of this are still murky and may be subject to federal regulations. But last week, the Department of Labor announced a proposal for a new rule that would allow states to move forward. But even so, states will need to clarify issues like whether workers can transfer plans across state lines and who will insure these plans.

All of this suggests a step in the right direction that will allow more workers to begin saving for retirement. But a lot more work remains.

Taxonomy: