The Chicago Public Schools (CPS) recently released its budget for the upcoming year. Pension and other structural debts continue to eat away at district resources and have left a gaping $1.1 billion hole in the current budget.

Paying for pensions isn’t cheap. Earlier this summer, CPS barely scraped together its required $634 million annual pension payment. The district did the right thing by paying the full amount on time, but in exchange, had to borrow an extra $200 million (in addition to the half billion it already needed) to fix cash shortages. To cover costs, the district will lay off 1,400 staff workers, including 480 teachers. CPS’ main source of revenue comes from city property taxes; even with city property taxes set at their maximum level (capped at inflation) and additional surplus tax funds and savings, CPS still needs additional revenue.

How does CPS plan on filling the rest of its massive budget hole? The district is counting on the state to deliver. CPS’ budget relies on the big assumption that the state will provide $480 million in pension funding. Governor Rauner has proposed supplying the district with relief, but only after a few labor trade-offs. Rauner wants to give local school districts’ the ability to limit what unions can and cannot collectively bargain for, something the Chicago Teachers’ Union isn’t going to give up without a fight. And Illinois still hasn’t been able to pass its own state budget. In other words, CPS is playing roulette with the school district’s finances.

How Chicago Public Schools Plans to Fill Its Budget Hole (in millions)

Lawrence Msall of the Civic Federation, an Illinois budget watchdog group, says, "It's difficult to even call it a budget because it has a half-billion dollar hole that the district hopes will be filled by Springfield — and we have seen little positive evidence that that will happen. To call this spending plan a budget challenges the common notion of having your expenses match your known revenue."

With just a few weeks before school, the district may be in for a mad dash for more funds. CPS could start the year without balancing its budget, but then they will likely need to make even riskier borrowing and cuts later in the year and down the line. Meanwhile, Chicago’s teachers, taxpayers, and students will continue paying for a system that doesn’t benefit the majority of teachers.

Taxonomy:One attractive selling point for the teaching profession is that there are schools everywhere; therefore there are teaching jobs everywhere. But, as several recent studies show, that story really only applies to first-time teachers. Once a teacher begins her career in a given state, she becomes very unlikely to teach in a different state.

A 2015 paper from the Center for Education Data and Research looked at teacher mobility within and across the states of Oregon and Washington. Over a period of 12 years, from 2001 to 2013, they counted how many teachers moved to a new school within the same state or across the border. It turns out that, while some teachers moved within a state, not many were willing to cross the border: On average, just 0.07 percent of Oregon teachers made a switch into Washington schools, and just 0.03 percent of Washington teachers made the reverse switch.

To put these numbers in context, Oregon teachers were about 24 times more likely to move to another school within Oregon than cross the border into Washington. Washington teachers were 64 times (!) more likely to move schools within the state than to cross into Oregon. The ratios were smaller, but still quite large, when they restricted the sample only to teachers working along the border. What's more, teachers were willing to move much longer distances within their state than cross the state line. Across both states, teachers were four times more likely to move to a new school 250 miles or more within their own state than they were to make a move of any distrance across the state boundary.

A 2017 paper from Janna Johnson and Morris Kleiner extended these findings nationwide. Compared to other workers, teachers are 39 percent less likely to move across state boundaries, making teaching one of the least mobile professions.

In 2016, the Regional Educational Laboratory (REL) Midwest conducted a study on mobility within and across Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. It included teachers as well as principals and district superintendents, and it came to similar conclusions. Across all three states and roles, educators were 50 to 100 times more willing to change schools within a state than to move to a new school across a state border.

So why are educators so reluctant to move across state lines? It can't just be about demographics. It may make sense that the female-dominated teaching profession would be filled with workers who prefer to take fewer career risks. But nationally, men are only slightly more likely to move across states than women (1.92 versus 1.86 percent). And, although the education profession may attract workers who value stability more than other people, that can't explain why they're willing to move so much more often and so much farther within their own state than across their state's border.

That leaves at least a couple likely explanations. First, each state imposes its own set of licensing requirements that makes it hard for teachers to seamlessly pursue jobs in a new state. Although many states have reciprocity agreements, these aren't always guaranteed and many teachers face burdensome and opaque licensure requirements if they want to move from one state to another.

Still, licensure requirements can't explain all of this. Teachers have stricter licensing requirements than principals or superintendents, and in the Midwest study teachers had especially low inter-state mobility rates. But even superintendents had much, much higher rates of mobility within states than across them.

There may be other features of the education system, such as funding rules, state standards, etc., that keep people working within their chosen state. State pension plans are playing a role here as well. All of the states in these studies enroll teachers, principals, and superintendents in statewide defined benefit pension plans. Those plans alone are not enough to retain early-career workers in the profession, and it's impossible for a statewide pension plans to act as a retention incentive for any particular district. But pensions do lock educators into a particular state. If a teacher intends to remain in education for her entire career, she's much better off, retirement-wise, staying in one state the whole time. By making just one move across state lines, educators can cut their retirement wealth in half. These penalties, and the fear of them, may be limiting transitions across state lines.

Regardless of why educators are unwilling to move across state lines, the data suggest the conventional wisdom is wrong: Teachers may be able theoretically to teach anywhere, but in practice they choose not to.

This post was updated on September 27, 2018.

The following is a guest post from James V. Shuls, Ph.D., an assistant professor of educational leadership and policy studies at the University of Missouri – St. Louis and a distinguished fellow of education policy at the Show-Me Institute. Follow him on Twitter at @Shulsie.

Pensions – once a topic only discussed by boring economists and old curmudgeons, are increasingly being discussed in political circles and popular publications. For example, last month The New York Times published “Bad Math and a Coming Public Pension Crisis,” which detailed how wrongheaded actuarial assumptions can wreak havoc on a pension plan’s financial health. As the article states, “The recommendations made by pension actuaries, like which mortality table to use, are largely hidden from public view, but each decision ripples across decades and can have an outsize effect.” In a recent paper with my colleague Michael Rathbone at the Show-Me Institute, I analyze another aspect of public employee pensions that can have a significant impact on a plan’s financial health, but often remain out of sight – pension investments.

Using data on four defined-benefit public school pension systems in Missouri, we analyzed the shift in investments between different asset classes from 1992 to 2014. This work follows a 2014 report by Pew Charitable Trusts and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation which analyzed aggregate economic and investment data from public employee pension systems. Similar to the Pew report, we found that Missouri’s teacher pension systems have shifted to riskier assets.

For example, the Public School Retirement System (PSRS), Missouri’s largest public employee pension system, held more than 80 percent of investments in fixed income and cash in 1992. That figure steadily dropped and by 2015, less than 25 percent of the plan was invested in fixed income and cash. Meanwhile investments in equities and alternatives have soared.

There is nothing inherently wrong with investing in riskier assets; indeed, riskier assets generally offer greater returns. However, they also offer greater volatility. This is another hidden problem which could spell disaster for public employee pensions. If the investments fail to generate the expected returns or even lose value, pension systems can lose a significant amount of money. Meanwhile, benefits for retirees are fixed, predictable, and effectively riskless. Despite this imbalance between riskier investing and guaranteed benefits, PSRS and the other Missouri teacher retirement plans continue to use high expected rates of return of 8 percent.

The findings of our paper reiterate the need for greater transparency and oversight of public employee pensions. For starters, plan actuaries should provide multiple funding scenarios using various expected rates of return, including what most economists agree is the risk-free rate--4, not 8, percent. This would give policymakers greater information in determining the appropriate contribution levels.

The need for greater caution in pension assumptions in Missouri is underscored by the fact that PSRS teachers are not part of Social Security. This means most Missouri teachers rely solely, or primarily, on their pension. If we want to ensure that teachers receive their promised benefits, we must keep a watchful eye on all of our plans assumptions, investments, and contributions. If we do not, we may hasten the “coming pension crisis.”

Taxonomy:*Today, marks the 80th anniversary of the Social Security Act passed in 1935. This blog is updated from an earlier TeacherPensions.org post.

Public sector unions praise Social Security. Except they don’t want it for all of their workers.

The National Education Association describes Social Security as the “cornerstone of economic security,” and Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers, describes it as “the healthiest part of our retirement system, keep[ing] tens of millions of seniors out of poverty [which] could help even more if it were expanded.” A couple of years ago, the Alliance of Retired Workers, affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and and American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), even made the Social Security Administration a blue and white frosted birthday cake for its 78th anniversary. This year marks Social Security's 80th birthday (and Medicare's 50th), and there will be events held across the country to celebrate. Also with cake.

But not all local government workers have Social Security. Over 6 million public sector workers are not covered by Social Security, including about 1.2 million public school teachers; in 15 states, public sector workers do not pay into or receive benefits from the system. If you were to ask, however, whether all state and local workers should have Social Security, most public sector unions would adamantly reply, no.

Why do unions hold such conflicting views on Social Security? The primary reason—pensions. Unions fear that extending Social Security coverage will signficantly cut into existing pensions, which are more generous to full-career workers in states that do not offer Social Security coverage.

However, public pensions in states without Social Security coverage offer more generous benefits because they were designed as a standalone benefit. Coordinating Social Security with state pension plans would likely result in equal or better retirement benefits overall for more teachers, especially those who do not qualify or receive much of a pension. What’s more, unlike pensions, Social Security is portable and does not penalize workers for moving across state lines. While the politics around teachers and Social Security coverage are at odds, Social Security could be a core part of improving teacher retirement plans. In particular, Social Security could provide a floor of retirement security for early career teachers who often leave the system with nothing.

See here for more information on teachers and Social Security coverage.

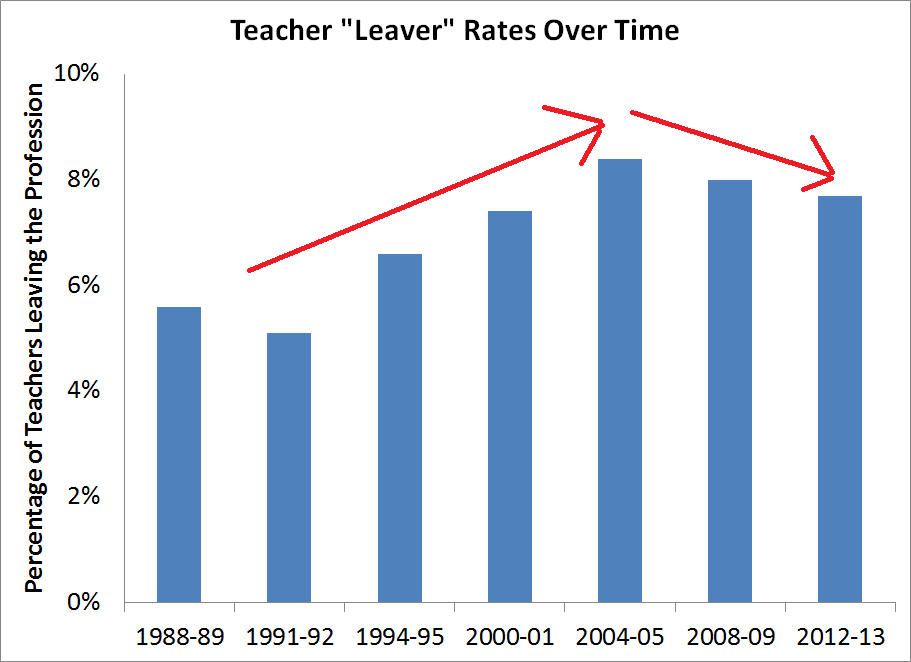

On the Diane Rehm show this week, I noted that the most recent data show that teacher retention rates are up, not down. This doesn't fit with conventional wisdom about the teaching profession, and several people have since questioned my source, because how can that be, what with the Common Core, new teacher evaluations, The War on Teachers, etc.? Even on the program, Stanford University professor Linda Darling-Hammond directly contradicted me, saying, "Our attrition rates went from 6 percent to about 9 percent recently..." Darling-Hammond would have been more or less correct if she had made that statement 10 years ago, but not anymore. The truth is that teacher attrition rates fell slightly during the recession and have kept falling.*

You don't have to take my word for it. Here's the latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Since 1988, NCES has tracked the number and percentage of public school teachers who stay in their current school, move to another one, or leave the profession. Although the "mover" and "stayer" rates are relevant to schools--all turnover causes disruptions and may lead to higher recruitment and training costs--the "leaver" rate is the key one for this discussion. As Darling-Hammond noted, the leaver rate did increase, from 5.6 percent in 1988-89 to 8.4 percent in 2004-05. But it fell to 8.0 percent in 2008-9 and then to 7.7 percent in 2012-13.

The data simply don't support the notion that teachers are leaving schools in droves in response to recent education reforms.** In order to fit the narrative that teachers are leaving because they feel less respected and less satisfied with their jobs today than they were in the past (a narrative that doesn't fit with actual survey data), we should be seeing a mass exodus of public schools teachers. But we're not.

What's far more likely is that large, macro trends are at work here, just as they are in teacher preparation. Throughout the economy, workers have become more mobile over time. That helps explain the long-term rise in the teacher "leaver" rate. Workers also tend to be especially mobile during good economic times and less willing (or able) to change jobs during recessions. That would explain the recent drop in teachers leaving the profession. The magnitude and timing of these forces might be different for teachers than for other workers, but teachers aren't immune from basic economics.

What will happen in coming years in the broader economy or in the teaching workforce is anyone's guess. The next round of data could show that we're back on the longer-term trend of rising attrition rates. In fact, that would fit fairly neatly with an improving economy and the emerging stories of teacher shortages. No matter what happens in education policy, I'd be willing to place a strong bet that teacher employment trends will continue to track the broader economy fairly closely.

*This is different than any changes over time, but there's also new evidence that longer-term teacher attrition rate was never as high as commonly thought. The estimate that "half of all teachers leave within five years" is definitely not true today and probably never was. Once you count teachers who come in and out of the profession or change schools, the rates look even lower.

**The NCES data do suggest that older, more experienced teachers saw the biggest increases, but it's unclear if that's relevant to policy or just an artifact of the Baby Boom generation nearing retirement age.

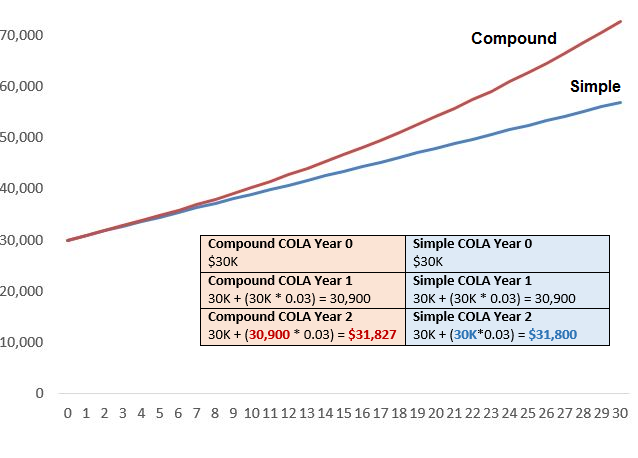

Taxonomy:Pension cuts stir up a lot of controversy, and most recently, Illinois’s Supreme Court rejected the state’s attempt to reduce benefits. Core to the debate was an often overlooked, but powerful policy lever: cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs). COLA’s are just one small mechanism for adjusting pensions, but they can have a big impact on worker benefits over time.

Take for example a retired teacher in Illinois. In the 1980s, state teachers were eligible for a simple, uncompounded, 3 percent increase to ensure their benefits kept up with inflation. In 1989, however, the state passed legislation allowing retired teachers to grow at 3 percent, compounded over time. While this may seem like a minor change, it materially affected retired teachers’ welfare and the state’s coffers. For a teacher who retires at age 60 with a starting pension benefit worth $30,000, her pension grows to $39,000 when she reaches age 70 under a simple COLA, but rises to over $40,300 under the new compound COLA. That same teacher’s benefits grows to $48,000 when the teacher turns age 80 under a simple COLA increase, but rises to over $54,000 under the new compound COLA. Simple interest only adds a fixed amount of interest based on the initial pension benefits. But compound interest grows “interest on interest,” growing from the amount of each prior year.

The Power of Compound Interest:

A Retired Illinois Teacher’s Pension Benefits

The purpose of a COLA is to adjust benefits for inflation. Thirty-thousand dollars today won’t buy the same things as $30,000 in the future. But compared to neighboring states, Illinois’ fixed 3 percent compounded rate is on the more generous side. Indiana, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Michigan only provide COLAs on an ad hoc basis, or make COLA decisions based on investment returns. Missouri and Kentucky, neither of which offer Social Security to its members (like Illinois), provides a COLA equal to the change in the Consumer Price Index, capped at 2 percent and 1.5 percent respectively. Social Security, which automatically adjust benefits for inflation each year, set its adjustment for this year at 1.7 percent.

Ideally, COLAs should be pegged to inflation to preserve benefits for retirees, like Social Security, but at the same time shouldn’t increase any faster. Illinois’ fixed compounded COLA outpaces inflation, but the state can’t change what it’s already passed. In 2011, the Illinois legislature tried scaling the COLA back to where it had been—a simple 3 percent —but the state Supreme Court ruled that doing so would impair benefits. A lower court rejected a Chicago pension reform law that would have also reduced COLAs for municipal workers for the same reason. One report estimates that the increased COLA benefits across all the state’s five retirement systems (not including Chicago) resulted in $1.3 billion in increased debt since the change.

While COLAs may just seem like an obscure, minor technical change, moving COLAs up or down have real consequences for teachers and states.

Taxonomy: