Most teachers in the United States won't be teachers for their entire career. They might leave the profession altogether, by choice or as the result of a life circumstance, or maybe put their teaching career on pause to pursue other personal or professional goals.

So, if almost every teacher will transition into and out of a pension plan, it makes sense to pay attention to how pension plans treat teachers at those transition points. Every state, with the exception of Alaska, relies on some form of a defined benefit (DB) pension plan, a retirement benefit based on years of service, age at retirement, and final compensation, to determine a teacher’s retirement benefit. Due to the structure of DB plans, they penalize employees for changing states or leaving the teaching profession.

One way retirement plans penalize mobility is through vesting periods. This is true for retirement plans in the public or private sector, but as Chad Aldeman has pointed out, federal law sets limits on vesting periods in private-sector DB plans, and there is no comparable rule for public-sector workers like teachers. States can and do set longer vesting periods than what would be required in the private sector. These long vesting periods makes it hard for new teachers to acquire retirement benefits. If they leave before they are fully vested, they will walk away with only their own contributions, sometimes with interest (keep reading to see why this matters).

Increased vesting periods aren’t the only rules states use to penalize teachers. The National Institute on Retirement Security (NIRS) recently collected state-specific information that illuminates how pension plans enact barriers that penalize teachers at various transition points across their careers. These sorts of barriers can reduce teacher pensions by 50-75 percent, depending on the state and the severity of their penalties.

To illustrate how those barriers affect teachers, consider a hypothetical teacher we'll call "Ms. Mover." In this example, Ms. Mover was born and raised in Florida near the Florida-Georgia border. After 15 years teaching in a Florida public school, she received a teaching opportunity in Georgia that she couldn’t pass up. Knowing she could continue living in Florida while working in Georgia, Ms. Mover accepted the position without regard to her future retirement benefits. We'll use this hypothetical story of Ms. Mover to illustrate four additional ways that state pension plans limit the ability of teachers like Ms. Mover to choose their own professional path:

1. Low Interest Rates on Employee Contributions

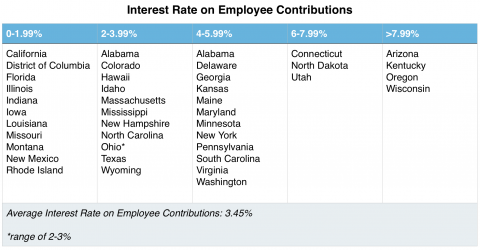

When a teacher chooses to leave prior to full retirement age, she can pull out her own contributions. However, not all states pay interest on those contributions. In some cases, this means that the teachers get back exactly what they put in and states get to keep any interest that accrued on those contributions. The table below groups states based on the interest rate they pay on employee contributions.

The average state pays an interest rate on employee contributions of 3.45%. This is better than the interest on a common savings account today, but it’s about half of what states assume they will earn on their own investments. In many states, teachers are essentially giving the state an interest-free or low-interest loan, because the state turns around and invests those contributions and expects a return of 7.5 or 8 percent. Even if the pension plan hits those 8 percent targets, teachers won’t see a dime of that interest.

For example, as Ms. Mover leaves Florida, she would be eligible to receive her own contributions back but without any interest. (She would qualify for a pension from Florida, but it might be worth less than her own contributions.) She would have been better off putting those contributions into a savings or investment account.

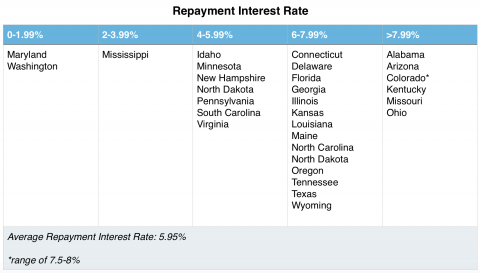

2. High Interest Rates on Service Credits

The inverse trend occurs when a teacher attempts to buy back into a plan. If they exit a pension plan but then decide to come back, they must come up with the interest that would have accrued on their contributions had they remained in the pension plan. Of the 31 states that told NIRS what they charge teachers, 19 used a different rate for re-purchases than they paid out to teachers. That means that they’re paying teachers less than what they ask of them if they want to return. If a teacher did want to buy back in, they’d have to somehow come up with the difference between the two sums of money.

Unlike the previous table, “Interest Rate on Employee Contributions,” the states in this chart are clustered closer to the right side. States like Alabama, Arizona, and Colorado, ask teachers to not only make up for any employee contributions, but pay up to 8 percent interest on those contributions.

Ms. Mover, our teacher from Florida, left Florida with only with her own contributions. If she ever tries to go back into the Florida pension system, she would have to come up with all the money she took with her, plus 6.5 percent annual interest.

This discrepancy essentially forces teachers to remain in the pension plan if there’s any question at all about whether they might return, because the risk of having to pay the difference between the two rates is too great. Meanwhile, every year they don’t withdraw their contributions is a year they’re stuck with relatively low investment returns. That makes for a complicated choice, and it’s one reason why so many teachers leave their money in state pension plans even when it might make financial sense to withdraw it.

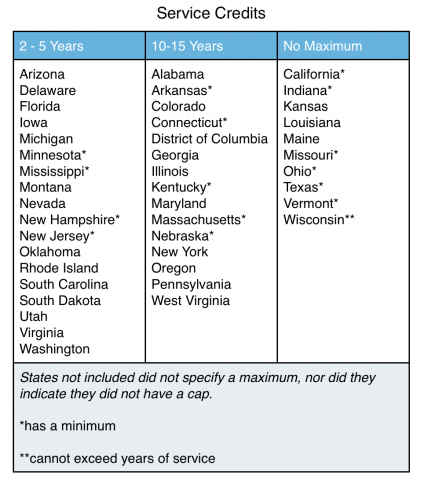

3. Limits on Purchasing Service Credits

Defined benefit pension formulas rely on years of service, so more years of service means a greater pension benefit for the rest of that teacher’s lifetime. All states offer teachers the ability to purchase additional "service credits," but many place a cap on the number of years of credit an individual can purchase. Those limits are another way that states limit teacher portability.

If we turn our attention back to Ms. Mover, we see how limiting these restrictions can be. Her fifteen years of teaching in Florida don’t travel with her. Instead, Georgia only allows her to purchase a maximum of ten years. Even if Florida gave her a decent interest on her own contributions, and even if Georgia allowed her to purchase credits at a comparable rate, caps like this will limit her future benefits. When she goes to retire at the end of her teaching career, at least five years of service won’t be factored into her retirement at all. The table below groups states based on the maximum number of years available for purchase.

As the table suggests, most states limit how many service credits a teacher can purchase. Only ten states allow teachers to purchase as many service credits as they would like. The most common or modal state restricts teachers to purchasing only five years of service credits.

4. Limits on Types of Qualified Service

Just because a state offers teachers the ability to purchase service credits doesn’t mean it allows them to purchase credit for any purpose. Limiting the types of qualified service (or absence from service) is another way states limit teacher portability.

In fact, 9 states deny teachers the ability to purchase service credits based on years of teaching in another state (they might allow someone to purchase credits for being in the military or serving in the Peace Corps, for example, but not for teaching service). As it turns out, Ms. Mover chose to move to the wrong state. Even though Georgia allows for the purchase of up to ten years of service credit, her 10 years teaching in Florida don’t qualify. Even if there were no transition costs, Georgia wouldn’t allow her to purchase service credit for her any of her time teaching in Florida.

These pension plan rules place constraints on teachers. When making professional decisions, teachers might not see the full picture or how they factor in their retirement. They might not realize the true cost of their movement across sectors or state lines until they reach retirement age.

Taxonomy:The teacher pensions world can get a little lonely. While nearly all of us could benefit from a brush-up on retirement saving practices, teacher-specific advice is hard to come by. To better understand how best to tackle the unique challenges educators face, I connected with NerdWallet's Arielle O'Shea. O'Shea has been reporting on and writing about personal finance for over a decade, and her work has appeared in Esquire, Money, The Billfold, Women's Health and XO Jane. You can (and should!) follow her on Twitter @arioshea.

Kirsten Schmitz: First, I'd love to hear more about your background at NerdWallet. What brought you to the investing and retirement space, and what keeps you here?Arielle O'Shea: I've been with NerdWallet for about a year, covering retirement and investing. I just recently launched the Arielle Answers column, and I also contribute to Forbes. I've been writing about all things personal finance — with an emphasis on investing and retirement — for over a decade. I love NerdWallet because its mission is essentially to do what I love: We want to bring clarity to financial decisions. Money can be so intimidating, and I want to make it approachable. This is a random story, but it kind of captures why I love what I do: Over the weekend I was in Lowe's buying some lumber for a project. I was so out of my element — I am not a DIYer but of course I was trying to save money by building a shed door myself — and as I was nervously waiting to ask the employee to cut the wood for me, it dawned on me: This is how most people feel about managing their money. I was so intimidated...I didn't know how to explain what I wanted, I wasn't even sure what I wanted, I didn't know the right language to use. So, I want to help put people at ease when they think or talk about money, and I think about that goal with everything I write.

Schmitz: Our work focuses on teacher retirement. About 90 percent of all teachers are enrolled in defined benefit pension plans, but our work suggests many teachers won't stay long enough to qualify for a decent benefit from the pension system. What advice would you have for teachers who aren't certain how long they'll teach?O'Shea: The biggest piece of advice in investing applies to this as well: diversify. Don't rely exclusively on your pension; contribute to an individual retirement plan like an IRA as well. If you're wondering about Roth vs. traditional, Roth is often the obvious choice — but there are a few factors you should weigh, including if you expect your tax rate to go up in retirement. For most people, this will be true, which is why the Roth is a great option — you'll be able to pull the money you contributed, plus investment earnings, out in retirement tax-free. You're effectively locking in today's lower tax rate since you don't get a deduction on contributions. Still, it's worth taking a look at your specific situation before you decide. Here is some more on this, from a post by my colleague.

Schmitz: With relatively high turnover in the teaching profession, many teachers will leave without vesting into the pension plan, or they'll qualify for only a relatively small pension once they retire. For those departing teachers, how should they decide what to do with their own contributions?O'Shea: For most people, the right choice is to roll what you can take with you over into an IRA. If you do it directly, you'll avoid any taxes and penalties — ask your plan how to do that, or the rollover IRA provider can help you. IRAs can be very low-cost — assuming you choose the right one — and you'll have access to a wide range of investment options. Choose low-cost index funds or ETFs to further keep expenses down.

Schmitz: I often see mixed messages about millennial savings habits. Either we're all drowning in student loan debt, ubering everywhere and postponing big purchases, or we're actually doing better than expected, and saving more than people think. How would your advice vary for younger or older teachers? Are there any things young teachers in particular should be aware of?O'Shea: This is one of my pet peeves for sure! You can find a study to support your views on millennials and money, whatever they may be: They're terrible at saving, they're saving more than their parents, they spend too much, they don't spend at all. I actually think millennials are doing well, considering all of the obstacles in their way (that student loan burden is real). But they're not ALL doing well, and of course how they're doing with their money is directly related to how much money they have. My advice for younger teachers: Save early and often. You don't have to save a lot if you save for a long time. You don't have to be an expert investor. Consistently saving small amounts of money adds up if you start young, due to compound interest.For older and younger teachers, some of the same advice applies: Know what you're working toward (a retirement calculator helps), limit debt, don't try to keep up with the Jones — for all you know, they're in debt! — and invest appropriately, which means taking risk, especially when you're young and you can weather market fluctuations. As you get older and closer to retirement, you can dial back that risk, but you still want to invest, not just save — saving alone, especially with today's interest rates, won't be enough to make your money grow and last through retirement.And then finally, limit investment expenses. These can really eat up your returns, and these days, you can get low-cost investments like index funds and even low-cost advice from robo-advisors. There's really no reason to pay 1% or more for your investments, unless you have a complex financial situation and you need a financial advisor.It’s no secret that we need to get more STEM teachers into our classrooms. These fields are high-growth and high-paying. But there’s a problem: we currently don’t have enough STEM teachers already in classrooms to get today’s students interested and prepared for these fields.

So how do we get more STEM teachers? One idea is to convince folks leaving a STEM job to start a second career in the classroom. 100Kin10 and Troops to Teachers are two among many organizations that recruit nontraditional candidates into schools.

But there’s a catch for these would-be teachers.

Career-changers, particularly in STEM fields, would most likely have to accept both a significant pay cut and lower retirement benefits.

To most people, the decrease in salary is probably obvious. But the lower retirement savings could come as a shock. This happens because these individuals will have two separate retirement saving plans. And, unfortunately, they will be unlikely to realize the full benefits of either.

Most likely someone who is switching careers from the private sector to become a teacher already has a 401k or similar retirement plan to which she and her employer have contributed. These plans are pre-tax and grow through regular contribution and returns on investment. However, to grow significant wealth these plan depend on regular contributions that can then grow through the life of a worker’s career.

For many, the pension plan they enroll in as a teacher won’t be enough to make-up for the lost years of contributing toward their 401k. This happens because teacher pensions take a long time to accrue wealth. On average, it takes a 35-year-old new teacher about 19 years for a teacher to build a pension that is worth as much as the amount of money they put into it through pre-tax paycheck contributions. It will take 13 years for a 40-year-old new teacher.

This carries serious consequences for a teacher who started teaching mid-career. She will need to teach a long time just to avoid taking a loss. To make matters worse, her 401k from her previous career will have grown only through interest while she was in the classroom. In all likelihood, a mid-career teacher will have far more money in her retirement if she had remained in her previous job, or if she had taught for her entire career.

With these facts in mind, changing careers to teach is a far more costly transition than previously thought. It’s clear that we need more STEM teachers in our schools. What’s not clear, is why those teachers who have years of professional experience in the field should have to take a significant pay cut and have their retirement benefits slashed in order to help our students. It’s unfair and makes it more difficult to recruit people with years of real-word experience to teach STEM.

States will need to develop innovative ways to ensure that highly valued mid-career STEM teachers do not face two barriers to the classroom: lower salaries and lower retirement savings. One way could be for states to forgo the pension system and instead contribute to the 401k of teachers who changed professions mid-career, or at least give teachers the option to do so. This way these teachers can continue to grow their 401k investments and avoid significant losses to their retirement funds.

Cassie Thompson is working toward balance. As a Head Start teacher in Cincinnati, Ohio, Cassie has strived to lead her 17 students, ages three to five years old, in both developmentally appropriate socio-emotional learning and academically rigorous kindergarten preparation. Says Cassie, “It isn’t supposed to be just finger-painting and running around – but finding a consensus on what pre-k should be, even within Head Start, is difficult.”

Early childhood education is challenging and often thankless work. A recent, comprehensive report out of the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California, Berkeley detailed the abysmal salaries, work environments, and professional development opportunities afforded to early educators nationwide. My Bellwether colleague, Marnie Kaplan, has more on this here, and the Department of Education released similar findings this June.

But as state and local policymakers seek to expand pre-k opportunities and improve support for early childhood teachers, they must also ensure educators like Cassie are given a viable path to save for retirement. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the benefit inequities we see at the K-12 level trickle down to the early childhood sector as well. Here’s a quick breakdown:

The workforce is fragmented

Some pre-k teachers work in school districts, while others, like Cassie, are employed by community-based providers. This distinction alone means two early childhood teachers with identical qualifications could have dramatically different retirement benefits. Further, even those early childhood teachers who are eligible to enroll in a traditional teacher pension plan are still unlikely to benefit from the rewards promised – their tendency to be lower-paid and more mobile keeps them from reaping the back-end rewards of a state plan.The workforce is underpaid

Early childhood educators are often compensated at much lower levels than K-12 school teachers—even when they work in publicly funded programs such as Head Start and state-funded pre-k. Pay is tightly linked to the ability to save for retirement. It isn’t that lower-paid workers are less cognizant of the need to save for their future, but rather, they simply have less money to save. We see this same scenario play out when analyzing women’s saving habits. While women are more likely to participate in retirement plans and contribute higher amounts, the average woman’s retirement account balance is half that of the average man’s. This isn’t because women are bad savers – in fact, they’re better – men just make more money and thus have more money left over to save.In addition to differences in salary, lack of access to pensions and other retirement benefits available to K-12 teachers exacerbates salary inequities for early childhood workers. Although a growing number of policymakers, funders, and early childhood advocates recognize the need to improve the compensation of early childhood workers, retirement security issues are rarely included in these conversations.

This is unfortunate, because most early childhood workers lack retirement savings options altogether or have the option to join only meager, poorly structured 401(k) plans. Lack of access to employer-provided retirement plans is also a major area of inequity between preschool teachers working in public schools, who are enrolled in public pension plans, and those working in community-based organizations, who may not be enrolled in any retirement plan at all. The latter group is often made up of smaller providers, who face the same obstacles to providing benefits as other small companies. Here’s a bright spot: we’ve covered some of the state-based efforts to address this problem broadly; while there’s still work to be done on these, if enacted, pre-k teachers would be beneficiaries.

But what about Cassie? Her non-profit employer offers a 403(b) retirement plan, giving her the portability to take her savings with her as she pursues a new opportunity outside of the classroom. The downside? Cassie’s employer does not match employee contributions unless they stay for several years – though Cassie was with her employer for two years, she won’t receive any match on her own contributions.

If Cassie is any example, increasing pre-k salaries is only the beginning. In order to enhance the status of the profession and build a more stable corps of educators who can seamlessly transition across sectors and locations, the early childhood sector needs to expand its reform efforts to include retirement offerings, too.

Pension reform isn’t black and white. Although stakeholders often frame the debate as generous pensions versus stingy 401(k) plans, in reality the options are far more complex. As states consider how to reform their public sector pension plans, it’s important to understand the grey area between the two extremes.

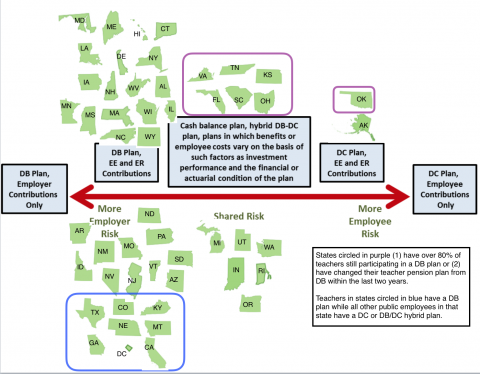

In reality, there’s a wide spectrum of retirement plan options that could meet the needs of workers and employers. The continuum below, originally created by the National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA), presents retirement plan types by employee and employer risk. We took NASRA’s spectrum chart and overlaid images representing which type of plan teachers are given in each state.

Over time, states have been shifting their public-sector pension plans from the far left-hand side, where the state took all the risk, closer to the center of the continuum, where the risk is spread more evenly between the employee and the employer. No state has put all of the burden of saving for retirement on workers alone. Plans that fall in the middle of the spectrum allow workers to move between professions with ease, while also giving employers greater predictability over future retirement costs. The shift toward the middle has been a good thing for public sector workers and for states. However, it isn’t happening at the same rate for all types of public employees.

When states are placed on the continuum based on their teacher plan type, it’s evident that a majority of states still enroll teachers in a traditional defined benefit pension plan. In eight states, those circled in blue, other groups of public employees are given more portable retirement plans, but teachers aren't. Teachers in states like Texas or California are enrolled in back-loaded defined benefit pension plans, while public-sector employees in those states have access to more portable defined contribution (DC) plans or a hybrid plan.

This situation is not a good deal for teachers. In fact, teachers have the least portable, most back-loaded retirement plans of any group of public-sector workers. This means that, when compared to their peers in other public-sector jobs, teachers have to work more years to earn decent retirement benefits. As Chad Aldeman and Richard Johnson point out, about three-quarters of teachers won’t ever reach the point in their teaching career where their promised future pension is worth more than what they themselves contributed. These teachers would be better off in more portable retirement plans.

There is good news, however, which is that the very long-term trend points in a positive direction. In the states circled in purple, new teachers are now receiving a DC or hybrid plan. This shift is a step in the right direction, but it will take time to show meaningful effects. Focusing on new teachers alone doesn't take away any benefits from anyone who might be counting on them, and it avoids political and legal hurdles that would be required to change benefits for existing workers. Still, the change will take time, and it won't address long-standing funding issues.

We’re in the midst of a slow shift away from back-loaded teacher pension plans. It may take a while, but there’s hope that state policymakers are recognizing there are better options that would provide all teachers sustainable and secure retirement benefits.

Taxonomy:Donald Trump has promised to make America great again. One thing he says he won’t look to change? Social Security. While maintaining the Social Security status quo might seem at the very least unobtrusive, it neglects an opportunity to extend coverage to the over 1 million teachers and 6.5 million government workers whose jobs go uncovered.

On February 29, Trump told Georgia rally attendees, “we’re going to save your Social Security without making any cuts. Mark my words.” He made similar remarks at an April rally in Wisconsin — both states, interestingly enough, extend social security coverage to only some of their teachers — and spoke favorably (though without specific recommendations) about preserving the program in a statement to AARP. Though no official stance on the topic appears on his website, and recent adviser statements seem to hedge toward cuts, let’s assume Social Security under Trump remains as is. He’s missing — perhaps not for the first time — an opportunity for real greatness.

While existing state pension plans aren't offering all workers adequate retirement benefits, Social Security at least offers them a solid floor of benefits. Expanding Social Security would help millions of uncovered workers, including all teachers in California, Illinois, and Ohio (where Trump will be accepting his party’s nomination tonight). Further, universal Social Security coverage would actually reduce the program’s existing deficit by 10% — yes, reduce — by more evenly distributing the program’s legacy costs. While Social Security isn’t designed to take the place of a stand-alone retirement benefit, it would provide all teachers with a much deserved and too often missed baseline of secure, nationally portable retirement benefits.

Neither candidate has broached the idea of universal coverage, though Hillary Clinton has proposed its expansion by increasing benefits for high-need groups, including widows and caretakers. Trump has yet to commit to any one approach – only promising not to make cuts. But to this point neither Clinton nor Trump has taken any steps towards addressing the benefit coverage gap that impacts millions of educators, many of whom will ostensibly head to the polls in November.

Taxonomy: