Cities and states faced with rising pension costs have begun to search for the most effective way to balance retirement promises made to workers with the need for fiscal sustainability and employer flexibility. Most prominently, a federal judge ruled last month that the city of Detroit can declare bankruptcy, opening the door for it to cancel or revise contracts such as those for retiree pensions. In Illinois, another state with a constitutional protection for government-worker pensions, the governor recently signed legislation that would raise the retirement age for mid-career workers and reduce cost-of-living adjustments for all workers who have not yet retired. Unions there immediately challenged the constitutionality of the legislation.

Another battle is playing out in California. In June 2012, San Jose mayor Chuck Reed convinced a seventy-to-thirty majority of his city’s voters to endorse changes to pension and retiree health care plans for city workers. The municipal unions filed a lawsuit the next day, and in late December 2013 a judge ruled that the pension changes violated the state constitution. Under what’s known as the “California Rule,” the Golden State’s constitution protects the right of workers, from their first day on the job, to accrue future benefits. (A dozen other states also use the California Rule as the legal protection for government pensions.) In other words, if a teacher is hired on January 1, 2014, her pension-benefit formula can never go down for the rest of her working career and into retirement, even if, for example, she lives until the year 2074.

While the California Rule protects pension benefits in perpetuity, it doesn’t protect the employee’s salary, health care, or the job itself. It’s easier to fire someone than to change her pension formula.

This results in a set of twisted ironies. First, it’s alright for employers to lower employee salaries but not to raise their retirement contributions. This doesn’t make any sense. If I ask you to take a 1 percent pay cut or require you to pay 1 percent more into your retirement plan, these two actions should have the same financial impact—yet the law treats them differently. Second, employers can change the components of benefit formulas but not the formula itself. Pensions are based on a formula where the benefit equals some multiplier (in California, it’s 2 percent) times salary (in California, it’s the highest twelve months of salary for workers who have at least twenty-five years of experience) times years of service. Employers can change an employee’s salary, and they can fire the employee (thereby ending their years of service). These things would obviously reduce an employee’s pension benefit, but the California Rule only protects the benefit formula, not the actual benefit.

Mayor Reed is among a coalition of California municipal leaders now leading a bigger fight. He’s sponsoring a ballot initiative that would change the state constitution and allow state and city governments to make proactive changes to retiree benefits. The initiative would protect any benefits that an employee has already accrued but would no longer guarantee employees the right to accrue the same level of benefits forever into the future. The attorney general recently gave the initiative a title and a short, one-hundred-word description. The first two sentences summarize that it

Eliminates constitutional protections for vested pension and retiree healthcare benefits for current public employees, including teachers, nurses, and peace officers, for future work performed. Permits government employers to reduce employee benefits and increase employee contributions for future work if retirement plans are substantially underfunded or government employer declares fiscal emergency.

Reed and his backers must now decide whether that language adequately captures the proposal and if it’s worth proceeding to a statewide vote. The initiative requires the signature of 8 percent of all registered California voters—that’s 807,615 people—in order to be on the ballot this coming November.

Ultimately, nonsensical pension protections such as these must come to an end. They’ve forced state and local governments to pay out ever-higher proportions of compensation in the form of retirement benefits instead of salaries. Such protections also act as an intergenerational wealth transfer from younger to older workers. Because they lock in benefits for existing workers, the only way for state and local governments to address funding problems is to target new workers. Nearly every state has created less generous plans for new workers, plans that will require them to pay more money up front, remain in their jobs longer before “vesting” into the system and qualifying for even a minimum benefit, and work longer before they retire with full benefits. This situation can’t last forever. We should protect the benefits that individuals have already accrued, especially those of present retirees and those nearing retirement, but we shouldn’t tie the hands of state and local governments’ decades into the future.

This first appeared on the Fordham Institute’s Flypaper blog.

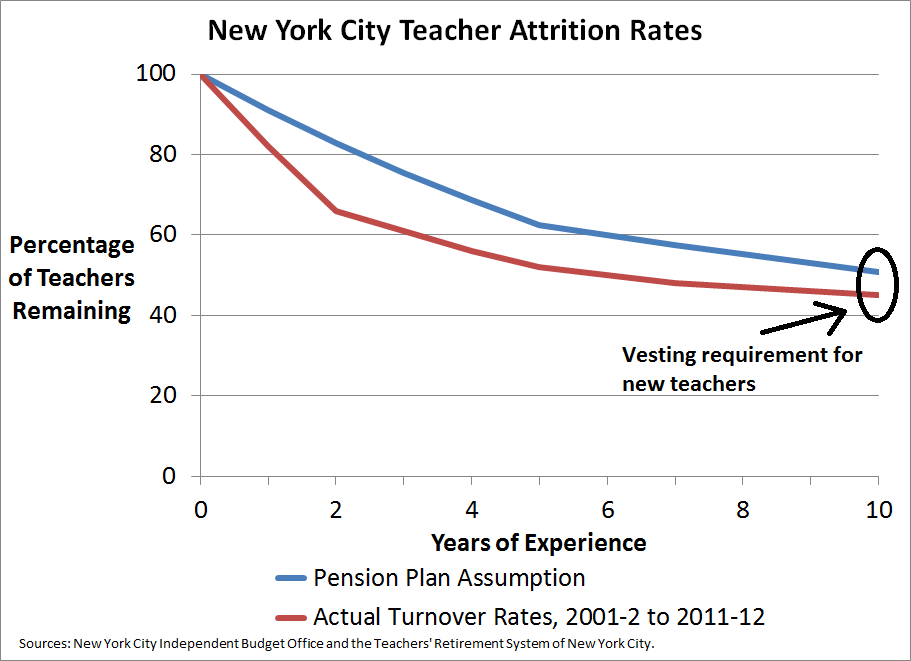

Taxonomy:All defined benefit pension plans make assumptions. They need to estimate how much money they’ll need in order to pay the benefits they’ve promised in the future. That requires them to calculate things like how much money they should save today, how fast that money will grow, and how long employees will live into retirement. Pension plans also need to estimate how many employees will qualify for a benefit in the first place.

In order to determine how accurate those assumptions are, I looked at the assumed and actual teacher turnover rates in New York City. The chart below shows the results. The blue line represents the plan’s assumptions, which I gathered from the Teachers’ Retirement System of the City of New York’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report. The red line shows the actual attrition rates as calculated by the New York City Independent Budget Office for the 9,437 teachers who began teaching in New York City in the 2001-2 school year, the most recent time period for which we have 10 years of data.

I focused on the ten-year survival rate for a reason. In order to cut costs and recover from the recent recession, New York City recently lengthened the vesting requirement, the time period employees need to stay in order to qualify for even a minimum pension, from five years to ten. The lines above show the consequences of this decision. Regardless of whether I use the pension plan assumptions or the actual turnover rate, the lines show that half of all new teachers will not reach ten years of service and will not qualify for a retirement benefit.

These teachers—remember, we’re talking about thousands of individuals a year—are eligible for a refund of their own contributions and 5 percent interest. They are NOT eligible for the full 7 percent return that the plan assumes it can earn on its investments, and they are NOT eligible for any part of their employer’s contribution. This is a significant amount of money in New York City. Last year, for every $1 the city paid in teacher salaries, it put $0.36455 into the city’s pension plan. Teachers who leave before qualifying for a pension forfeit this entire amount. A beginning teacher with a bachelor’s degree in New York City earned $45,530 in salary last year, meaning the city contributed $16,597.96 on their behalf into the pension plan. But if the teacher leaves before ten years, they get none of this money; the employer contributions stay in the pension plan to supplement the retirement of those who remain.

A recent report looked at whether we could change this situation by shifting away from traditional defined benefit systems and offering more compensation in the form of base salaries rather than benefits. It found that these cost-neutral changes would allow New York City to increase total teacher compensation including salary and benefits for the vast majority of teachers.

In education policy, we often talk about “teacher turnover” as a problem for schools, employers, and communities. In doing so, we forget about the affected individuals. As in Washington, D.C., the New York data shows that the consequences of teacher turnover are extremely high for individual teachers, the thousands who leave the profession every year.

Illinois recently passed pension reform legislation with a number of complex provisions (read the full bill here). It will add new funding streams to the state’s woefully under-funded pension plans, limit pension “spiking” whereby employees cash out vacation and sick leave to artificially inflate their benefits, raise the retirement age for current workers, limit annual cost-of-living adjustments, and allow a limited number of employees to choose a defined contribution plan over the traditional defined benefit. Union leaders have called the bill “pension theft” and are already planning to sue to prevent the bill from taking effect.

To better understand the legislation and the issues around it, I spoke with Illinois State Senator Daniel Biss. A former mathematics professor, Biss represented the 17th District in the Illinois House of Representatives from 2011 to 2013 before his election to the state Senate. As a Senator, Biss served as co-chair of a bipartisan working group exploring solutions to the state's pension crisis and co-sponsored the final legislation. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Chad Aldeman: First, can you say why you are interested in pension reform, and what made this bill important?

Daniel Biss: I’m interested in pension reform because the first two years of my service in the Illinois General Assembly were years that followed a very significant tax increase and yet saw extremely deep cuts in discretionary spending to areas of public service that I cared deeply about, the reasons that I entered public service in the first place.

The size of our pension payments was so large that if we tried to address our budget problems without looking at pensions, we would be signing ourselves up for deep and never-ending impacts on the rest of state government. I just couldn’t get to a place where that seemed acceptable. I sought out changes to the pension system that ultimately strengthened and preserved it for those who rely on it the most.

This bill makes significant changes to the pension system in a way that seeks to do three very important things. The first is to achieve significant budgetary savings. After this legislation, our state payments over the next 30 years will be $160 billion dollars lower. Number two, this bill achieves those savings in a way that is consistent with my policy priorities, namely sheltering those with the smallest pensions and those who are most reliant on their pensions, as well as those who have served the longest. Number three, for the first time in history, Illinois will be making its actuarially required payments in keeping with national actuarial standards. Not only do we get on an actuarial payment schedule, we put in place protections to ensure that we stay on that schedule going forward.

Aldeman: The bill lays out a path to full funding by making the actuarially required payments immediately and beginning a separate stream of payments to pay down the existing liability starting in 2019. Can you say more about this plan and what was the rationale for this timeline?

Biss: There are 3 different streams of money that the bill directs to the pension system. The first is just the regular actuarially required payments. That’s calculated independent of the next stream. Over and above that, 10% of the annual savings from the policy changes built into this bill will go back into the pension system. The third piece of the funding is, again, over and above the first two streams, is a set of additional payments that begin in 2019 and expand in 2020. In the past, Illinois has borrowed money to pay its pension obligations through a series of bonds. Some of those bonds expire in 2019 and 2020. That means the state’s debt service will reduce in those years. Instead, that so-called “found money” will also go back into the pension system.

We want to make sure that, as money becomes available in the coming decade, that we don’t find ourselves back in this awful situation again.

Aldeman: Am I reading correctly that the changes apply to legislators? Was that a complicating factor in the negotiations?

Biss: It is true. Whatever the bill does for other pension systems—for state employees, teachers, and state university employees—the bill either replicates the same policy for legislators or asks more of them.

I don’t know if that was a concern for some people or if there were resentments. Nobody ever mentioned anything. Very few of us were prepared to do something like this to teachers, state workers, and university employees unless we were prepared to do it to ourselves as well.

As an example, in 2010, Illinois created a new “Tier 2” of benefits for employees hired after January 1, 2011. It’s a relatively stingy plan. This bill didn’t change anything for those workers at all. The only exception is that the bill did have a cut for Tier 2 legislators. I just couldn’t look myself in the mirror and sponsor a bill that left me off the hook.

Aldeman: One component of the bill is a gradual increase in the retirement age for current employees. For example, if an employee is 46 years or older as of June 1, 2014, they face no change, but if they’re between 45 and 46, their retirement age will increase by 4 months. The law creates tiers like this, adding four months to the retirement age a year until the employee is less than 32. Anyone 32 or younger would have their retirement age increased by 60 months (5 years). What was the rationale for creating this tiered system?

Biss: This is probably one of the parts of the bill that feels the fairest to some people. If you’re close to retirement, moving the retirement age is a lot to ask. If someone is 59 and planning to retire at 60, changing their retirement age is changing their life in a really extreme way. On the other hand, telling someone who’s younger, say 40, just doesn’t seem as much to ask, particularly in a climate where other workers in the private sector are retiring later.

I have always felt you need to protect those close to retirement. In a bill I introduced a year ago, we had somewhat crude bands. Those bands were larger than what emerged in the final bill. The bigger bands worked ok, but they unfairly penalized people depending on when their birthday fell in relationship to the bands.

The Senate Republicans came up with the idea we compromised on. It may be difficult to write it out, but it’s phased in smoothly and doesn’t make someone say, “I can’t believe I was born only two days late.” It’s less capricious and arbitrary.

We wanted to phase it in over a reasonable time period while sheltering those who are close to retirement. However, part of the challenge for a place like Illinois, because we have so much debt, is that an unbelievably large portion of our liability is associated with workers and retirees who are over the age of 60. In other words, the vast majority of our unfunded liability is to retirees. What this means is that changing the retirement age just can’t move the needle significantly enough on the cost side.

We were asked, “How can you possibly touch retirees?” but once you realize that two-thirds of our liability is associated with people over the age of 60, it doesn’t seem plausible to make a significant fiscal change while leaving retirees untouched.

Aldeman: There’s been quite a bit of questioning about the legality of the changes. Article XIII, Section 5 of the Illinois State Constitution says, “Membership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency of instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.” The last part, “shall not be diminished or impaired” has been seized on as prohibiting changes like what’s in this bill. Can you explain the counter argument for why these changes are legal?

Biss: There are a number of different arguments. I would lay out two here.

First, there is consideration given to the class of affected individuals in this bill. It is consideration to the class rather than an opportunity for each individual to renegotiate their contract. For those still working, their annual contributions will be reduced by 1%. For the entire class, there is a significant new right in the form of additional funding. The Supreme Court has said the Constitution has protected the right to a benefit, but we're also creating a new right to fund the benefit properly and therefore guarantee its fiscal health and stability. We’re not only going to an actuarially funding schedule, we’re going above and beyond that. All of this is money going to the retirement system and therefore to the employees.

The second argument is simply one of balancing priorities. The Constitution does include Article XIII, Section 5. But it’s a long constitution and it includes other things too, such as a free public education and health and welfare and safety. It’s very clear that we’ve had to cut spending on things like public education in a way and to an extent that imperils the quality of our services.

My expectation would be that the courts decline to rule narrowly but will recognize that this was an attempt to balance between different priorities, all of which are important, some of which are statutorily and others which are constitutionally protected. Though it was a difficult and painful struggle internally, I felt like the public harm from doing nothing at all was unacceptable to the people of Illinois. I hope the courts will weigh that seriously and carefully as they make a determination.

Aldeman: The bill includes an optional defined contribution (DC) plan where individual employees can invest their own and their employer’s contributions into a portable savings account. However, the bill caps eligibility at 5% of employees and doesn’t apply to new employees? What was the rationale for the cap and why not allow new employees to join?

Biss: Regarding new employees, the champions of this provision were insistent that it be cost-neutral. Because the package of benefits offered to new employees after 2011 was so poor, it was impossible for it to be cost-neutral if offered to new employees.

Regarding the cap, I would make two points. Number one, there is some anxiety that if you chase a lot of people out of the system and significantly slow the flow of incoming employee contributions, you would de-stabilize the system. If we went to a full DC system, we’d shut off all contributions and potentially destabilize the system, the precise opposite of what we were seeking to do.

There’s also a broader point to make. If you don’t think the classic Final Average Salary Defined Benefit plans are the way to go, there are a lot of better options than throwing everyone into a 401k. I sympathize with the desire to make larger structural reforms, but for those of us who have a strong interest in thinking carefully and rationally about the structure of benefits, this seemed like more of a political down-payment to some members who have an ideological attachment to DC plans more than it was a carefully designed solution to a real problem.

Aldeman: You’re a Democrat in a Democratic state. You just helped author a bill that will reduce pension payments to government workers like teachers, state employees, and state university employees. Labor groups sponsored a call-in campaign lobbying legislators against “pension theft.” What does this say about the politics of pension reform?

Biss: First of all, we in the Democratic party, especially those of us who identify as progressives, have a strong attachment to our friends in organized labor and a strong preference for being on the same side as them on issues when it makes policy sense. The fact that you saw this bill pass with such robust bipartisan support is an indication of how broadly shared the view was that this was a necessary step if we were going to achieve the kind of fiscal balance that allowed us to spend dollars in the places we want to spend. Some of that is a pure policy judgment—that we need to do this to provide budget relief—and some of this was a procedural point about showing the public that we’ll take necessary actions on the spending side of the ledger in order to make compelling arguments on the revenue side. A lot of Democrats came to the conclusion that this was an important thing to do for our state.

The public was very conflicted and was not particularly enthusiastic about any of the options. In that environment, compromise is politically attractive. Showing the public that you can find a way to bridge differences, even if they don’t love everything that comes out of it, is a way to build the public’s trust. You saw what can only be described as an embarrassing spectacle of three out of the four Republication candidates for governors to finding ways to oppose the bill. They did not want to see the General Assembly and the Governor find legislative success. One of the four candidates, to his credit, stood up and said it was the right thing to do and he voted for it. Many other votes were based on partisan reasons.

Aldeman: Illinois has now passed pension reform bills in 2010 and 2013. Are you done for the foreseeable future, or are there issues that you’d still like to see resolved?

Biss: The immediate answer is that the state of Illinois has, I believe, 628 pension plans. The bill we passed last month made significant changes for 4 of them. Of the 628 funds, five are paid for by the state—one each for state employees, legislators, teachers, state university employees, and judges. Judges were excluded from this bill, but that that still leaves 623 pension systems, including five where the city of Chicago is the employer. There are more than 600 small pension plans, mostly for municipal police and fire officials.

The city of Chicago is about to go over a cliff, a pension cliff. That cliff is not going to be pretty. There’s an extremely strong interest in making steps on the Chicago and Cook County pension plans. The other ones are in varying shape. Some are 20% funded and some are 80% funded. That variance brings in delicate, difficult issues that need to be addressed.

Looking further on, I mentioned earlier that the benefits for new employees under “Tier 2” are not very generous. What I didn’t mention is that it may be in violation of federal law for being so exceptionally stingy. Finally, we have this wacky system of misplaced responsibilities where school districts outside the city of Chicago negotiate contacts that impact teacher pensions but then the fiscal responsibilities fall on the state. The issue of structure has also gone largely unaddressed.

In short, there is plenty left to do.

Taxonomy:We've invited a range of panelists—from union leaders to economists to teacher voice organizations—to participate in an online forum on teacher pensions. We’ve collected their responses and have posted them here, in their own words, on a rolling basis this week.

Today's guest post comes from Elizabeth Evans, the founding CEO & board member of the VIVA Project, which works to dramatically increase classroom teachers’ participation in important policy decisions about public education. Elizabeth is a recognized national leader for building unconventional alliances and bringing innovative approaches to solving difficult public policy problems.

A “crisis” is sometimes in the eyes of the beholder.

If you are paid to manage a public pension fund, you’re not feeling much of a crisis. If you are elected to be accountable for public pensions, you are not feeling much of a crisis. If you are a state or municipal executive facing growing pressure on your annual operating budget, political pressure to hold the line on new revenue and an aging, growing or otherwise active workforce, you’re feeling a fiscal crisis. Too often, rather than tackle broader fiscal priorities head on, it might be convenient to call it a “pension crisis”.

In the face of this dynamic if you are a public employee, teachers included, you are likely a little, or more than a little, nervous about your pension management.

The public pension crisis has a lot to do with the broader broken compact between Americans and their government over fiscal priorities. Yet again, it’s a place where public school teachers are the leading edge of the great debate about what it means to be an American.

In conversations with teachers in Texas, Ohio, New York, and Iowa during the last week, I’ve discovered that a few things about the state of public teachers pensions. At VIVA, we’ve yet to take a head-on look at teacher pensions. That said, compensation is certainly a critical issue for the mission-driven educators who participate in a VIVA Idea Exchange.

Teachers definitely factor in their retirement planning as part of their job decisions. A teacher from New York made it clear that without a pension, he would leave teaching. A teacher in Texas, where most teachers do not have defined retirement benefit programs, reports many of her peers are working full time after retirement because they do not have adequate benefits to cover their basic living costs.

Ultimately, it’s up to us, the public, to decide how much we value public education and the professional staff we trust to educate our children. When we drive good teachers out of the profession because of poor financial security, we’re directly affecting students. All the teachers I spoke to recognize that their long-term financial security is vulnerable to the political and fiscal storms currently swirling through our government.

For example, a teacher in Iowa, a state with strong fiscal health and a substantial surplus, recently discovered that her pension contributions were recently raised to cover a multi-billion dollar shortfall in the state’s teacher pension fund. Now she’s wondering what the status of the fund will be when she’s ready for retirement (albeit a long way off). A teacher in Ohio put the teacher workforce demographic trends in more dramatic terms when he expressed hope that there would be public school teachers to support him when he’s ready to retire!

What can we do to assuage teachers’ concerns? We need to make sure our public interests align with our public investments. I mean this in both the general and specific sense. First, we need to repair our approach to governance and re-stitch our social compact with government employees. The current disdain too many people have for the existence of government - and by extension any and all government employees - is destructive and misguided. In addition, we need to broaden accountability for investment decisions and outcomes of public funds just as we are for teaching and learning. How about opening up accountability for public teacher pension fund management to much larger numbers of teachers? Several of the teachers I spoke to would like to have more options about where their money is invested. At minimum, they want more information about where teachers’ pensions are investing and how investment decisions are made.

At VIVA, we’ve proven that crowd sourcing technology can create new avenues for productive mass collaboration and demonstrate the public will for effective, achievable public policy improvements. Why not use technology to create innovations that allow public employees, and us taxpayers in general, to have more and better information about how our public pension funds are being managed? Let’s create new ways for investment managers to know what the beneficiaries of these funds need. The increased transparency could also create early warning systems that would prevent pension underfunding or avert widespread failures to provide retirement funds to our public school teachers.

At the same time, we need to let’s look beyond the pension issues and into the deeper challenges in our public budgeting process. We’ll need to re-build our public compact in order to achieve any of these goals.

We've invited a range of panelists—from union leaders to economists to teacher voice organizations—to participate in an online forum on teacher pensions. We’ve collected their responses and will be posting the authors’ contributions here, in their own words, on a rolling basis this week.

Today's guest post comes from Dean Baker, the co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, DC. He is frequently cited in economics reporting in major media outlets, including the New York Times, Washington Post, CNN, CNBC, and National Public Radio.

Hyping the difficulty of public employee pension funds is one of the few growth industries in the current economy. There has been a concerted effort by many well-funded organizations to highlight the problems facing these funds. In fact, Students First, the school reform organization started by Michelle Rhee has even made the elimination of traditional defined benefit pensions one of the main planks on its school reform report card.

The reality is that teacher pensions face a mixed situation. The finances of many large funds are quite solid. Actuaries consider an 80 percent funding ratio an acceptable level of funding. (This means that they have assets on hand that can cover 80 percent of their projected liabilities over the next three decades.) Many teacher pension funds have assets that place them well above this level.

For example, New York State’s teacher pension fund was nearly 90 percent funded at the end of 2012. A recent report from Morningstar showed that North Carolina’s teacher fund was 94.0 percent funded at the end of 2011. The report showed that Texas’ teachers fund was 81.9 percent funded as of August 2012, and all of Washington State’s teacher funds were more than 100 percent funded.

Clearly, these funds have no problems. They can continue current funding and benefit levels for the foreseeable future with no problem. There are however many funds that fall below the 80 percent acceptable level. In many cases this is due to a temporary drop attributable to the stock market plunge following the collapse of the housing bubble.

Even though the stock market has more than regained its losses from the downturn, the slump still has an impact on funding ratios as a result of the valuation methods used by most pension funds. Pension funds typically take an average value of their assets over a four or five year period. As a result, the depressed market values of 2008 and 2009 would still be included in a 2012 pension valuation that was based on a five year average.

However this means that underfunding is likely to be sharply reduced through time. Next year’s five year average will substitute 2013 for 2008. Assuming that the market does not plunge in the immediate future, this will mean substituting a market valuation that is more than 70 percent higher than in the year being replaced. The following year 2014 will be substituted for 2009 in the average. This would be a gain of more than 50 percent, even assuming no further rise in the stock market from current levels.

Together, these two increases in valuation will raise funds that are somewhat below the 80 percent cutoff, back to the acceptable level of funding. This would likely be the case with Minnesota’s teacher retirement fund, which Morningstar listed as being 73.0 percent funded In July of 2012 and possibly also the case with Maryland’s teacher plan which was funded at a 65.8 percent level in June off 2012.

The fact the finances of most pension funds are virtually certain to improve substantially in the near future might explain the urgency of pension fund opponents for quick action. If the stock market were to just grow in step with the economy through the rest of the decade, many of the funds that now appear to be facing serious shortfalls would be nearly fully funded, even without further changes.

However, there are some pension funds that are seriously troubled. This is almost always due to the fact that politicians opted not to make the required contributions for a long period of time. Chicago’s former mayor, Richard M. Daley, can probably get an award in this category, failing to make the required contributions to Chicago’s pension funds for close to a decade.

There are other examples like Daley, but these are the exceptions. Even in these cases, making up the shortfalls will not impose an unbearable burden. For example, in the case of Chicago, which has seriously underfunded all of its public pensions, the additional required contribution to address the problem is equal to roughly 0.5 percent of the city’s projected income over the next three decades. This is hardly a trivial sum, but it does not imply bankrupting the city to meet the contractual obligations to its workers.

It is worth noting that some of those now raising the alarm about pension funding gaps bear much of the responsibility for the development of these gaps in the first place. Moody’s stands out in this respect. It recently adopted an accounting method for pensions where it uses a much lower discount rate to assess the liabilities of pension funds. This can double or even triple the reported liabilities of pension funds, which are generally calculated using the rate of return that pension funds’ expect on their assets. Moody’s has justified the change in procedures by arguing that the new approach is a sounder, more cautious methodology.

There are good reasons for rejecting Moody’s new approach. Most importantly it would effectively imply substantial over-taxation of current workers to allow under taxation in future years. It would also lead to sharp gyrations in required pension fund contributions.

While Moody’s claims to be acting responsibly in changing its accounting procedures now, it ignored concerns that were raised about pension fund return assumptions during the run-up of the stock bubble in the late 1990s. This run-up caused the stock market to vastly exceed its historic price-to-earnings ratios. In fact, at its peak in 2000, the price to earnings ratio in the stock market was over 30, more than twice its historic average.

Given this extraordinary price to earnings ratio, it would have been impossible for the stock market to provide the same returns going forward as it had in the past. Nonetheless, Moody’s assumed that the market would continue to provide its historic rate of return in assessing pensions, effectively assuming that the price to earnings ratio would rise ever higher.

One result of the negligence of Moody’s and other rating agencies was that cities contributed very little to their pension funds in these years. When the bubble burst and they suddenly needed to contribute more to their pensions, many state and local governments were poorly prepared to allocate the additional money. Hence we had cities like Chicago that went much of a decade not making their required payments.

If Moody’s and the other rating agencies had adopted a reasonable system for evaluating pension liabilities in the stock bubble years, many pensions might not be facing their current shortfalls. Applying its new methodology that exaggerates these shortfalls is increasing the damage they have already done.

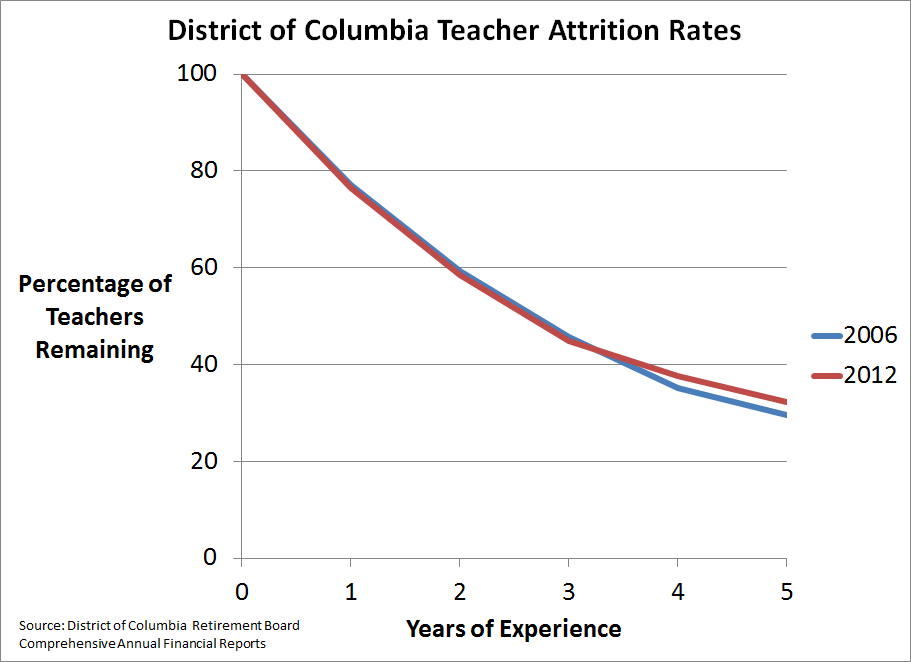

Taxonomy:If you follow news about the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) closely, you could be forgiven if you thought teacher turnover had increased since the schools were handed over to mayoral control in 2007. But, at least according to the city's teacher pension plan, turnover hasn't increased at all; it's actually declined slightly.

Since 2007, DCPS leaders Michelle Rhee and Kaya Henderson have led controversial reforms like a new evaluation system, a comprehensive pay-for-performance plan, and school closures. They've used the new evaluation system ratings and school closures to lay off or fire hundreds of teachers each of the last several years. Meanwhile, media outlets like the Washington Post have run numerous stories highlighting high teacher turnover rates. Just last week, Mayor Vincent Gray was assailed for the "untenably" high teacher turnover rates.

By all accounts, DCPS does have high turnover rates. But that does not prove they've risen due to recent policies. According to the District of Columbia Retirement Board, retention rates have barely budged at all since 2006. The DCRB administers retirement benefits for 4,500 active plan members, including all permanent, temporary, part-time, and probationary teachers. According to the Common Core of Data, DCPS employed nearly 3,800 teachers in 2010-11, so even though the retirement system also includes other classes of workers employed by DCPS (certain public charter school employees are also eligible to be participants), the vast majority of DCRB's members appear to be DCPS teachers.

Each year, DCRB issues a Comprehensive Annual Financial Report. In order to estimate how many teachers will vest and become eligible for a pension, DCRB uses “withdrawal” tables to estimate how many teachers will leave in a given year. These estimates are typically based on actual turnover rates, and they are used to determine how well the plan is funded and how much money it needs to contribute each year. The graph below looks at DCRB's withdrawal assumptions for 25-year-old teachers beginning their employment in 2006 and 2012. Both lines have relatively steep drop-offs for the first three years but then begin to flatten out somewhat. Notice that there's almost no distance between the 2006 and the 2012 lines. That's because DCRB assumes that teacher turnover rates have stayed nearly the exact same over the last six years. Either DCRB is wrong and they're ignoring whatever rise that Rhee and Henderson's policies have caused, or DCRB is right and the rest of us need to check our assumptions.

This graph does provide another piece of evidence confirming that teacher turnover is very high in DCPS schools. According to these estimates, only about 30 percent of new teachers will stay in DCPS schools for five years. The rest will leave. That's a problem for the district and schools as they deal with finding and training replacements, let alone the parents and students at schools that are forced to deal with instability.

When discussing teacher retention, we often focus on the consequences for districts, schools, and students, but we almost never talk about the consequences for individual teachers. That's unfortunate, because the penalties are steep and they affect a large number of people. In DCPS, the 70 percent of teachers who do not reach five years of service will not be eligible for a retirement benefit. They can receive a refund of their own contributions, with no interest, but they are not entitled to any contributions their employer had made on their behalf. That policy will disadvantage huge numbers of DCPS teachers and endangers their retirement security.

Ultimately, it's important to have these sorts of nuanced discussions about teacher retention. We should consider the overall rate, look for any recent trends and try to identify causes, and acknowledge that the consequences for high turnover affect everyone involved--parents, students, employers, and even the departing teacher.