This Black Friday, consumers across the country will line up as retailers slash prices. This Thanksgiving, however, public pension plans are in for some sticker shock and are about to wake up to deals that were too good to be true. For the first time, public pensions are adding up and disclosing just how expensive their performance fees are.

Up until recently, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) didn’t know how much it was paying in fees to private equity managers. There are two main types of fees: performance and management. Management fees are usually 2 percent of assets and cover the cost of advisory and administrative services. Performance fees are usually 20 percent of profits, over a specific target, and are meant to reward managers for high performance. Unlike management fees, however, CalPERS hasn’t kept track of the cost of performance fees. Instead, the full price tag on performance fees hasn't been fully totaled up and/or publicly disclosed. Later this week, CalPERS will announce just how much it has paid private equity firms over the past decade and is expected to be in the billions.

This new scrutiny comes after states and local governments already started to shift more and of their investment portfolios toward alternative investments like private equity. From 2006 to 2012, 11 percent of pension assets were invested in alternatives. By 2012, that share had more than doubled to 23 percent.

Who knows if the shift to alternatives would have grown this fast with greater disclosure on fees, but it’s clear that public pensions need greater transparency. Unlike the private sector, which must abide by federal regulations on reporting and fiduciary standards, public pensions have faced significantly less scrutiny. The Treasurer of California, John Chiang, recently wrote an open letter to CalPERS and the California Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) to disclose all fees charged to public pension funds.

Finally under public pressure, California and other states will need to start facing the cold truth about their fees. With new transparency, states will likely push for lower fees and maybe get a better deal from private equity firms.

Taxonomy:Imagine you're a school district leader. For a variety of reasons, you want to increase the retention rates of your teachers. Let's say you discover a magic intervention that will boost teacher retention rates by 50 percent, but the intervention can only be applied to one group of teachers. Your choices are to apply this magical intervention to:

A. Teachers just in their first four years on job, or

B. All teachers with 15 or more years of experience.

Which one would you pick? If you care about maximizing retention and limiting turnover, you should pick A.

If this result sounds at all counter-intuitive, consider where turnover rates are highest already. The figure below comes from a recent report from Marguerite Roza at the Edunomics Lab. It shows national turnover rates from the Schools and Staffing Survey, broken down by experience levels.

As the figure shows, turnover is highest for teachers with very little experience. Just on logic alone, districts should focus their interventions on the biggest problem areas. Reducing early-career retention rates by 50 percent would cut them from 13.5 to 6.75 percent. In contrast, reducing turnover rates among teachers with 20-24 years of experience doesn't do much. The same 50 percent reduction for this group would boost retention rates from the already-high 97.8 percent all the way up to 98.9 percent. That's an impressive figure, but it's not much bang for the buck.

But wait, there's even more to this story. Turnover rates are cumulative, so an early-career intervention has positive ramifications for years on end. A teacher who stays for a few years doesn't suddenly become more likely to leave--in fact, the opposite is true. As teachers stay and grow into the profession, they become less likely to leave. A district boosting retention rates for just early-career teachers is likely to see higher cumulative retention than a district focusing its efforts at the back end.

Let's go back to the initial question and run the numbers. Using the same NCES estimates as the base retention rate, Option A focuses the magic intervention solely on four years, the first years of a teacher's career. In Year 1, 100 percent of teachers are affected, 93 percent of teachers are around to receive the intervention in Year 2, etc.

Option B applies the same magic intervention over a wider range of years, to all teachers with 15 or more years of experience. But there aren't that many teachers left by then. Using the same NCES figures compounded year-after-year, only 25 percent of teachers would still be around to receive the magic program. Under this scenario, these teachers become nearly guaranteed to stay, but the vast majority of teachers won't ever experience this stage of their career.

Although this exercise is obviously absurd and only meant as an example--a 50 percent boost in teacher retention rates overnight would indeed be magic--the implications of it should be clear. Late-career incentives, such as large salary increases or backloaded retirement benefits, simply don't have the same potential to shift teacher retention rates as early-career investments. Contrary to current practices, districts should be investing the majority of their retention efforts on early-career teachers.

Taxonomy:In my 401(k) plan, my retirement savings is directly equal to the amount I contribute, the amount my employer contributes, and the amount those contributions grow over time. That's not how teacher retirement plans work. 90 percent of teachers earn retirement savings based on a formula relying on their age, salary, and years of experience. The contributions made into those plans are related but not directly tied to what teachers actually receive in benefits.

This discrepancy is due to debt. My 401(k) plan has no debt, and indeed my employer contributes what they promised each year, nothing more and nothing less. Pension plans, on the other hand, can and do accrue large debts. They promise a certain level of future benefits but often fail to save enough in the present. As debts rise, teachers, school districts, and states must make higher contributions than they otherwise would. They must pay debt costs in addition to the cost of providing benefits.

Pension debt alone now eats up to about 10 percent of the average teacher's compensation. Remember, this is money that is spent on teachers but isn't actually going to them now or in the future; it's money just to pay down debts that were accrued in the past.

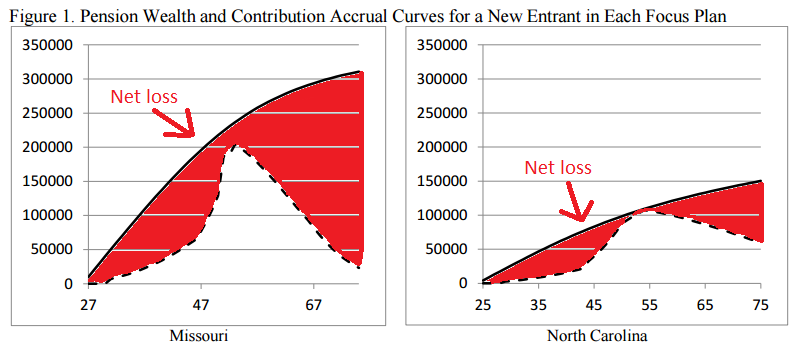

A new CALDER working paper, "Benefit or Burden? On the Intergenerational Inequality of Teacher Pension Plans," helps illustrate this distinction. The graphs below, a modified version of Figure 1 from the paper, shows the total contributions that will be made into the pension plan over a teacher's working career (the solid black line) versus the actual benefit teachers would receive at a given stage of their career (the black dotted line). These graphs are from Missouri and North Carolina, but the paper models similar graphs for Tennessee and Washingon. The authors also show national figures and the percentage of states that suffer from this discrepancy. I've added the red bars to show the gaps between the two lines, representing the net loss teachers face at every stage of their career.

As the graphs illustrate, teachers at all stages of their career face a net loss from their retirement plan. They and their employers are paying more into the pension system than they'll ever get back. The actual losses vary across a teacher's career, but at no point in any of the states the authors studied would the teacher finally surpass what was contributed on her behalf. On average, Missouri teachers are losing about 10 percent of their salaries and North Carolina teachers are losing about 3.5 percent.

It doesn't have to be this way. As the authors note, there are retirement plans, like my 401(k) plan, that never accumulate debt costs. There are other retirement plan designs, such as cash balance plans, that are also unlikely to suffer from these problems. In keeping the existing defined benefit pension plans, policymakers are choosing to preserve a system where teachers and their employers are contributing more than teachers will ever receive back in benefits. This is a bad choice, and it's a big reason why teacher salaries remain low and flat.

Taxonomy:The following is a guest post from Kirsten Schmitz, a former LEE Policy fellow at Bellwether.

There’s a narrative that women are bad investors; they’re risk averse, quick to spend, and ill-informed about their retirement savings. A new report out of Vanguard, however, shows just the opposite.

The study found women are more likely to participate in workplace savings plans, and that when they do, they also contribute in higher amounts than their male counterparts. Further, men and women show almost identical amounts of investment risk.

But despite all this, when it comes to retirement savings, women just can’t win.

Despite women being more likely to participate in plans and contribute higher amounts, the average woman’s retirement account balance is half that of the average man’s. The discrepancy lies within the pay gap. It isn’t that men are superior savers – they just make more money. Vanguard found that when controlling for income, the balance shifted, with women posting higher balances.

Teacher pensions play an interesting role in these findings. Over three-fourths of teachers (76%) are women. Pensions are often lauded as more secure than a defined contribution plan, and a strong choice for females in particular. And for the small percentage of teachers who remain in the classroom (and in the same state) for 30 or more years, pensions may be better. But what about those who don’t?

A changing workforce means many teachers may move out of state, or leave the profession entirely, before gaining any net benefit from their pension plans. The Vanguard report debunks the idea that 401(k) plans disproportionately favor men – women report better outcomes and higher rates of participation.

Because the underlying issue is a pay gap, and not a savings gap, defined contribution plans strike a balance between portability and functionality. According to the Vanguard study, women are more than capable of planning and saving for retirement on their own, at least compared to men, and DC plans such as 401(k)s and 403(b)s would give teachers greater mobility than pensions do.

Should federal funds designed to support the education of low-income students be diverted to paying down state pension debts? That’s the subject of an amendment in the current bill to reauthorize the No Child Left Behind Act, and it’s the question behind a recent report from Stand for Children. The report, authored by Jessica Handy, the Government Affairs Director at Stand for Children-Illinois*, looks at the consequences of a large “surcharge” that the state of Illinois levies against any school district using Title I or IDEA funds to hire teachers. I talked to Handy to learn more about how this issue affects Illinois schools. The following interview has been edited for content and clarity.

Chad Aldeman: Your new report is about a teacher pension “surcharge” paid by Illinois districts. Can you explain what it is and why it exists?

Jessica Handy: Yes, in Illinois the state pays for the majority of teacher pension employer costs. School districts technically employ teachers and set their salaries, but the state pays the employer contribution into our defined benefit plan, which is called the Teachers’ Retirement System. School districts pay only a very small percentage—0.58 percent of their payroll—into TRS, with the exception of teachers who are paid with federal funds.

Federal funds are primarily Title I funds, IDEA funds, or other funds that are targeted specifically to areas of high poverty where student need is higher. If a teacher is paid with these federal funds, the district must also pay 36 percent of their salary as a surcharge into TRS. This creates a disparity. If a district hires a teacher with local funds or with state funds then the school pays just 0.58 percent into TRS, but if they hire a teacher with federal funds, then the district must pay 36 percent of their salary into TRS. That’s what we’re calling the TRS surcharge.

Aldeman: What does that surcharge mean for a district making personnel decisions?

Handy: It means districts are doing one of two things.

Some districts have said, “Our priority is to hire teachers with [federal] money, and we’re just going to take the hit.” They know that of every federal dollar they receive, 64 cents will go toward that teacher’s salary and the other 36 cents must go to TRS. [In other words, it will cost a district $68,000 to offer a teacher a $50,000 salary.] Some districts are willing to take that hit because it’s important to them to have full-time, certified teachers there to work with their students.

Other districts have gotten more creative. Instead of hiring a certified teacher, these districts decide to purchase something, like textbooks, where they can spend every dollar of their Title I funds, instead of just 64 cents on the dollar. Or they hire two part-time aides instead of one certified teacher because those aides don’t participate in TRS (they have a different retirement system). We’re seeing more and more districts making decisions that actually impact student learning, where the interests of the kids aren’t coming first. It’s a combination of what’s good for my kids and how can I keep the most of my money Title I money in my district to spend without TRS taking a cut off the top.

Aldeman: You mentioned that districts are changing their decisions over time. What about the surcharge? How has that 36 percent changed over time?

Handy: Good question. 10 years ago, that rate was less than 10 percent. The state was paying about 10 percent of total teacher payroll for the employer contribution, and the federal contribution was (and continues to be) the same as the state’s employer contribution rate. It was easier for districts to deal with when they were keeping 90 cents on the dollar.

But the state was not paying enough into our pension system, so unfunded pension debt rose. Federal law allows states to use federal funds to pay into the pension system, but states can’t charge federal funds a higher rate than they pay into TRS through either state or local payments. So as pension debt has grown and as the state has started prioritizing pension payments in a way they hadn’t in the past, the federal funds rate has grown right along with it. The TRS surcharge on federal funds has gone from 10 percent to 36 percent over an eleven-year period.

I should also add that this issue does not impact Chicago. Chicago Public Schools is the only school district in Illinois that pays its own employer contributions for teacher pensions. CPS teachers are members of a different pension fund, not in TRS. So no matter what fund the money is coming from, CPS is on the hook for paying the pension, whether it is a state- or local- or federally-funded position.

Aldeman: Can you say something about which districts lose out the most under this arrangement and why that might be?

Handy: The districts that get the most federal funds are the districts that have the most student needs. Most of these are Title I funds, which are specifically targeted to students who live in poverty, especially when there is a high concentration of poverty, so those students can get the support they need to meet academic standards.

We’re now tapping into funds which are very specifically supposed to be going to the neediest students to pay Illinois’ massive pension debt. But it is not the right source to be using to pay our pension debt. It’s almost the worse source we could be using because this is money that’s specifically targeted to our neediest kids in our poorest districts.

The Education Trust put out a report this March (“Funding Gaps 2015”) that showed that Illinois has the most inequitable school funding of any state in the country. When we are already faced with such inequities in our school funding system, adding this extra burden on poor districts is ridiculous.

Aldeman: Do you know if this issue applies to other states?

Handy: We’ve dug into this quite a bit, and from what I can tell, Illinois is an outlier.

The way we know that is, in the House version of the ESEA rewrite, an Illinois congressman named Bob Dold added an amendment that would ban the practice of levying the TRS Surcharge on poor districts’ federal funding. Dold’s amendment would say that federal funds can only be used to pay up to the normal costs of pensions. States can’t pay their pension debt with federal funds, they can only pay the actual costs of benefits going forward. That amendment went through without a ton of discussion or opposition.

After it went through (ESEA is now in conference committee) people started to pay attention and wonder, “How would this affect us?” Some states are a little concerned. They pay the same rate into a retirement system for locally paid or federally paid teachers, but that rate might be more than the normal costs. Those states worry they might get caught up in something where they’re not being a bad actor like Illinois is by inequitably saddling poor districts with a surcharge.

I’ve been talking to some national pension groups who’ve done surveys, and from what we can tell, this is very much an Illinois-specific issue.

Aldeman: Can you speak to what the Dold amendment might do and what impact it might have on Illinois?

Handy: The Dold amendment came out of conversations that the congressman had with his local education advisory committee, which mainly consists of school districts in the northern suburbs of Chicago. Those districts range from some of the neediest to some of the wealthiest in Illinois. But all agreed that taking 36 percent off the top of federally funded teacher positions is an unfair practice. So they brought this issue to Dold.

In Illinois, this amendment would end the practice of charging the 36 percent TRS Surcharge. We would have to go back to charging 8 percent, which is our normal cost rate. That difference, which is about $65 million that was coming from federal funds before, would get shifted to the state. The state would have to pay that in their certified pension contribution every year.

It would be a relatively small price tag for the state, but it’s also a price tag that fluctuates every year. If more and more districts get creative with accounting, and eventually if districts decide that they’re not willing to take that pain as it grows, more and more of them will shift [from hiring full-time teachers] to hiring aides or buying textbooks with their Title I money. Districts will find creative ways to shrink that $65 million anyway, so it’s not a real number, it varies every year.

So we’re hopeful that the amendment or something similar will make it into the ESEA, but if it doesn’t we’re also prepared to file our own legislation in Illinois and try to tackle it here.

Aldeman: Who are the opponents to addressing this surcharge at the federal or state level, and what is their argument?

Handy: It’s hard to say, because the issue is a no-brainer. Our report is called “An Education Funding No-Brainer,” and it really is. We can’t find any group that would say that this is a fair way to fund pensions.

TRS is chaired by the Superintendent of the State Board of Education. In August of 2013 the then-chairman, Chris Koch, brought the surcharge before TRS to let them know about school districts that had complained about the inequity of the practice. TRS agreed and decided to change the policy. They sent a letter to school districts saying, “We’ve changed this for you, you no longer have to pay this 33 percent (it was 33 percent at the time). Now you can pay just normal costs.”

Then in May 2014, the legislature reversed that change as part of their budget implementation bill. It was a very high-level decision that the General Assembly made in the process of budget negotiation, to keep those federal funds subsidizing their payment to TRS as part of the last minute budget deal.

I think the only one I could say would be opposed to Dold’s amendment…well, probably nobody in theory, but in practice, it could be our leaders as the next budget gets negotiated and finalized.

Aldeman: Any other final thoughts or things you think people should know about this issue?

Handy: This issue is just a piece of a larger funding issue that we’re working on with Illinois’ big funding reform bill. The bill passed the Senate, it went on to the House, but did not get a vote.

In general, the more we look at funding reform, the more I personally see that pensions play a really big role in funding equity. I don’t think it’s a lot of people’s first instinct to look at pensions as something that could be used to improve funding equity. But this is one small issue that costs poor districts $65 million a year.

Another issue we’ve seen with pensions is that Illinois and a few other states pay pension contributions for all teachers, in contrast with the majority of states where local districts pay the pension contributions for their own employees. There are a lot of equity issues there as well. Wealthier districts with higher salaries have higher pension costs. When these are paid by the state it disproportionately benefits wealthier districts, whereas districts that have less money, lower salaries, and lower pension costs get less from the state on a per-teacher basis. The state’s paying their pension contributions as well, but lower-income districts would be better off if the state would put that money currently allocated to pay pension contributions into something that could be allocated more equitably.

As we’re thinking about funding equity, I think pensions are something that we should all, whatever state we’re in, take a look at. We should remind ourselves that those teacher pension dollars really are education dollars, and ask whether we are really using that money in a way that prioritizes equity and drives better student outcomes.

*Disclosure: Stand for Children is a Bellwether client.

Taxonomy:Today is Veterans’ Day, and as we honor those who served our country, we should consider the benefits that we provide veterans and their families.

We have had a number of military families write to us about their need for portable retirement benefits. While teacher pension plans may work for workers who stay in a single state for an entire working career, they severely punish mobile workers. Because military families frequently move, military spouses who work as teachers won’t meet their state’s minimum service (or vesting) requirements to qualify for a minimum retirement benefit. Instead, their teaching service years are spread across several different states and they may end up not vesting at all, or having a number of partial pensions that are far less generous than if they had stayed in one state. State pension aren’t transferrable, at least not for free, and a teacher who splits a career across multiple states will end up with significantly less in lifetime benefits.

Yesterday, Congress approved a historic overhaul of the military pension system. Under the new bill, new military personnel will have access to 401k-type benefits. A sharp improvement to the old system, the new portable plan would allow many more members to qualify for benefits earlier on and take their benefits wherever they go. Under the current defense pension plan, enlisted personnel need to serve a minimum of 20 years before qualifying for any benefits at all.

In terms of retirement reform, Congress is moving in the right direction. States should follow suit. If more states offered teachers portable benefits, more military spouses would be able to earn adequate retirement benefits for their service in the classroom.

Taxonomy: