Last week Elite Daily ran a viral piece titled, “If You Have Savings in Your 20s, You’re Doing Something Wrong.” The essay gives tempting advice: enjoy life, spend while you’re young, and don’t save for the future.

The article has generated heated responses from many. Luckily, most millennials aren’t following Elite Daily’s advice. According to a TransAmerica survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers, Millennials are actually starting to save earlier than previous generations. While the median Generation X worker reported only beginning to save for retirement at age 27 and Baby Boomers at age 35, Millennials started saving at an early, unprecedented age 22. While participation rates are lower than older generations, still, the majority of Millennials are saving for retirement. Seven out of 10 Millennials have already started saving for retirement. Vanguard and Bank of America Merrill Lynch client surveys report similarly high participation rates for its 401k plans.

Millennials Are Starting to Save for Retirement Earlier:

Participation Rates in an Employer-Sponsored Retirement Plan and/or Outside Retirement Savings (percent)

Source: TransAmerica, “Millennial Workers: An Emerging Generation of Super Savers,” 2014. Based on a nationally representative sample of 4,143 workers.

Moreover, Millennials are not just participating at high rates, they’re also setting aside real money. Those who participate in a 401k or similar plan contribute 8 percent of their salary—one percentage point higher than Generation X.

Given the overall poor savings habits of many Americans, we should celebrate, not criticize, the fact that many younger workers are doing a decent job of starting to save. Who says that Millennials can’t feel like they’re 22 and be savvy at saving, too?

Taxonomy:Michael Hiltzik of the L.A. Times and Andrew Biggs of AEI had a spirited Twitter debate last week about whether state pension plans were too generous or not generous enough. They were arguing specifically about California and mostly NOT about teachers, but there are kernels of truth in both their arguments with important implications for teacher pensions.

The debate centered around Biggs’ 2014 piece on “pension millionaires,” those state and local workers who qualify for guaranteed payments in retirement worth more than $1 million. Biggs ran the numbers for full-career state workers in every state and found that it’s not that uncommon for government workers to qualify for retirement benefits worth more than $1 million.

Hiltzik’s main counter-argument was three-fold. One, these workers don’t actually have $1 million that they can spend—it’s merely an estimate of how much they’ll be entitled to based on their many years of government service. Two, the figures do not include Social Security. Since about one-quarter of public employees (and about 40 percent of teachers) do not earn Social Security, their pensions need to be larger to provide them adequate retirement savings. And three, lots of workers don’t stay a full career, and in fact pension benefits on average are much lower than Biggs’ calculations.

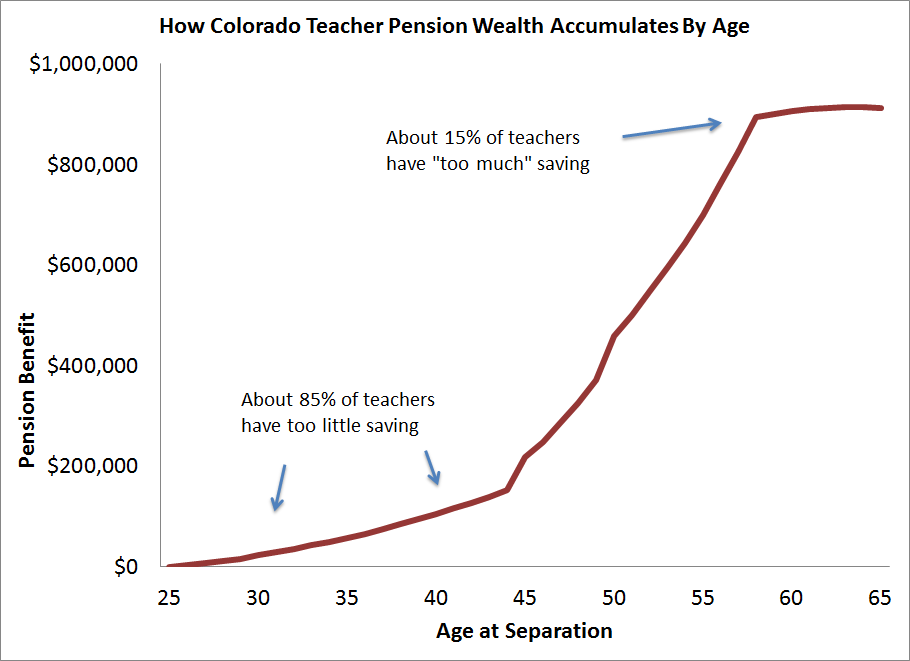

So who’s right? They both are! The same pension plan can simultaneously be too stingy for some workers and too generous for others. The average can be modest even as the low end can be very low and the high end can be quite high. To show what this looks like, consider the graph below, which shows how retirement benefits grow over time for Colorado teachers (I’m using Colorado here as an illustrative example, but California and other states would have similar trajectories, and neither state offers teachers Social Security).

Retirement savings grow very slowly in a teacher’s early career. In fact, when we tried to estimate how much a teacher needs to save today in order to have a secure retirement tomorrow, we found about 85 percent of Colorado teachers are on the too-low side. The pension plan is not generous enough for them.

But a Colorado teacher following the graph above qualifies for a steep ramp-up in her benefits at the back-end of her career. Her retirement wealth will quadruple between the ages of 45 and 58, and she can retire at age 60 with a pension worth the equivalent of $906,000 in today’s dollars.

That doesn’t work out to a crazy-high amount in annual terms, but her “replacement rate,” a ratio comparing her pre- and post-retirement incomes, would be more than comfortable. In fact, her total savings rate would surpass what most experts think she’ll actually need in retirement. As Michelle Welch and I calculated in a brief last fall, she has more retirement savings than if she had saved 20 percent of her annual salary each year, compounded at 5 percent interest. She is probably “over-saving” for retirement and would likely be better off with a larger share of her compensation coming in the form of salary increases.

So both Hiltzik and Biggs have valid points, but there’s a danger in solving the wrong problem. If policymakers took Biggs’ argument to the logical extent, they would focus most of their attention on capping pensions and ensuring that no one became “pension millionaires.” But Hiltzik's preferred solutions of preserving or perhaps even amplifying existing plans aren’t right either. The status quo is the problem here; preserving it leaves 4/5 teachers with insufficient benefits. Simply adding to existing formulas won't solve that problem. Because pension plans are extremely backloaded, boosting the formula gives a little bit more money to early- and mid-career workers and a LOT more to full-career workers. That would amplify rather than solve the fundamental fairness problems within existing pensions plans.

That’s why our approach here at TeacherPensions is to focus primarily on the lack of generosity buried in most teacher pension plans. Too many teachers are losing out on the chance of a stable, secure retirement. It’s not fair--nor is it worth the political fight--to take away from the “winners” who played by the rules of the current system. On the other hand, the problems can’t be solved with the same old formulas. We have to do something different.

We have two new briefs out this week, one looking at how pension plans affect short-term workers, about half of all teachers, and another looking at the effects on medium- and longer-term workers, another 30 percent of all teachers. Read the reports to get all the details, but the summary version is that most teachers are making a bad trade--they suffer from low salaries while they work in exchange for the promise of better retirement savings when they leave. For most teachers, that promise never becomes a reality.

One common response to our pension work, and even to this new set of research, has been to argue that pension plans would be fine if they were fully funded. That is, if the stock market didn't have recessions, and if we could somehow make politicians stick to their funding promises, and if state predictions about longevity and salaries and inflation and all other sorts of other variables were perfectly accurate, then all our problems would be solved.

There are 968 billion reasons why this is a magical argument, of course, but even if we somehow could erase the funding problems, pension plans would still have enormous flaws. That's because pension plans don't just have funding problems; as we focus on in our work here at TeacherPensions, pension plans also have design problems. Improved funding could help the situation--policymakers might stop cutting teacher benefits and may even start to reverse the slide. But there are fundamental, structural problems here too. Wishing away the funding problems won't change the fact that current defined benefit pension plans are simply not delivering sufficient retirement benefits to the majority of the teaching workforce.

Taxonomy:- Mary W. is a former nurse and second-career teacher from Georgia who reached out to us to learn more about the current research on pensions and Social Security. Social Security coverage varies within the state of Georgia, and some school districts provide coverage while others do not. I interviewed Mary to hear her story and perspective on retirement planning as a teacher.What follows below is a lightly edited transcript of my recent conversation with Georgia teacher Mary W.Leslie Kan: Can you tell us a bit about yourself, what you teach, and how many years you’ve taught? Why did you decide to become a teacher – what led you to this profession?Mary W: I’ve been in healthcare for about 23 years. I’ve done a lot of different things: I’ve owned a business, and I was a registered nurse for 23 years. I still hold my nursing licensure.I thought about teaching at one point. I had thought about working in a school with children, but I just didn’t know when that was going to happen. Then I got a nursing position at an elementary school in 2010; I worked at that position and I was very successful at it. I started befriending some teachers in the school, and I started learning how the school operated. I started bonding with some kids in my school, and I realized there was something about teaching that I liked. I liked the interchange between me and the students.So I found out about a master’s of teaching and certification program at a nearby university. Last year was my first year teaching in special education. I teach in an inclusion setting. Teaching blended some things that I had been doing anyways. It was not easy to do, but I’m glad that I did.Leslie: Did your previous experience as a nurse influence whether you would stay in the public sector?Mary: I’m staying in the public sector—I know this sounds bad—because I want to make sure that I get a retirement check. I like working with people; I like working with other human beings so remaining in the public sector is a good fit for me.I was actually able to come from the ERS [Employee Retirement System] system from the state of Georgia (I had about 3 years with the state of Georgia as a regulator in healthcare when I was working for the Department of Community Health) and I was able transfer that time into Georgia TRS [Teachers Retirement System]. I think this will be my 8th year in TRS. And then of course, in 10 years, I’ll be vested. A lot of my decisions have been based on the realization that I need some type of pension for my retirement. I’m starting late, because in healthcare, as a nurse, I was able to work different hours and do different things, such that I couldn’t always work full-time because I had children that I was raising. So I had to be very flexible. Now I’m playing catch up.Leslie: Many school districts in Georgia don’t provide its teachers with Social Security. Before you decided to join the profession, were you aware that teachers did not receive coverage?Mary: I had no idea that this was occurring. I was really shocked this summer when I found out that there were groups—large groups—of working professionals who do not pay into the Social Security system. I had always known that people who were self-employed, because we had a business, had to pay that 12 percent into the system. I had never known about teachers, and I think it’s really weird that there are teachers who have no clue that this is going on. There are some teachers that know but they don’t talk about this openly. I had one teacher who was my mentor this past year. When I told her that I turned down a job because they didn’t take Social Security, she said, “Oh, [the neighboring] county doesn’t pay Social Security either.” And I said, “That’s not a big deal to you?” But then I realized that she was in our system, which did pay into Social Security, so it must have been a big deal to her or she would have stayed in the neighboring county's system. She was very close to retirement.Leslie: And how did you first find out that teachers are not covered by Social Security?Mary: I went on a job interview for a neighboring county and in the midst of the interview I asked about benefits. I’m pretty thorough, I’m older, I might be a second-year teacher, but I’m pretty savvy and I know what kind of questions to ask about jobs. The principal happened to mention in passing, “Oh, and you know that we don’t pay Social Security.” I stopped. I said, “You don’t pay Social Security? You mean your system does not pay into Social Security for the employee.” She just nonchalantly said, “No, we don’t. But we have a 403b or 457 and that makes up the difference because we give a matching for your contributions to those retirement plans.” In so many words, I told her that was in addition. My [current] school system offers those, too [in addition to Social Security]. It’s not like those plans are something that can make up for not having Social Security.That was that. The principal offered me the position, but I told the principal that I would have to refuse the offer because of her board's decision not to pay social security. I would have loved to work at that school.I think there a lot of teachers who really don’t realize that this going on. They’ll take a job, and they don’t realize they might be making a little extra money in the short-term, but in the long-term, they’re not paying into the Social Security system and losing out on a heck of a lot of money.I already had a job at a school system that pays into Social Security. This was just a job that was offered to me in a neighboring county. Then I found out there was another neighboring county that did not participate in the Social Security system. One of the things I’m interested in knowing is which counties in Georgia pay in and which don’t pay in.We’re thinking of moving to the mountain area in our state, or perhaps another state. But that’s a whole other conversation on portability. I think it’s crazy. I need to know what county I can go to in north Georgia that pays into the Social Security system. I think it may be one thing if I was younger. In Georgia, TRS pays the same in my current county as it does in any of the others; it’s the same pension plan in all the counties. So TRS is not going to make up for not having Social Security. Also, a matching contribution to a board controlled retirement plan does not make up for a national security net like the Social Security system.Leslie: Could you describe how you first learned about your current retirement plan? Which aspects were easier or more challenging to understand?Mary: I first learned about TRS when I transferred from a general state retirement plan into a teacher retirement plan. I researched the plan a little bit before I transferred my money.I don’t really find any of it easy. I guess the easy part is how it is automatically taken out, how it automatically takes out a percentage. It just goes on auto-pilot, and you don’t start worrying about it until you get closer to retirement. One of the things that I have witnessed from friends who have retired is the difficulties. They offer you some counseling and try to help you as much as they can as you get ready to retire, but I don’t think they give you as much information as you should have. In other words, what would be the benefit of staying 25 years instead of 20 years? Where’s the offset, the breakeven mark, where it doesn’t really pay to stay in the system, when could I come out of the system and make more money elsewhere, rather than continuing to stay in the defined benefit plan?I guess it’s because I’m not really close to retirement. But I wonder about those things. Because I do think there is a point where it makes sense to retire. Because at some point you’re paying into a system that’s not going to give you back a return that would make a large difference in your monthly retirement check.There’s just not a lot of help for people who are thinking about questions like this.Leslie: In your ideal world, what would a good retirement plan look like?Mary: It would be more equitable for everyone. Meaning, it would give you the same amount of money that you would need for all your living expenses, for everyone across the board. I just don’t think retirement in this country is equitable. It’s hierarchal, and it’s tiered. There are people who work so hard all their life, as opposed to someone who sat in an office. It’s the social structures we have that are so delineated, and not everyone gets what they need. It needs to be the same in retirement plans. I think everyone should have a pension plan that takes care of all of their needs.Leslie: And what advice would you give to new teachers just starting out in the profession about retirement?Mary: They probably need to make sure that they know a little bit about how their plan works. New teachers get very preoccupied with lesson planning and classroom management, and get very weighed down with all the responsibilities that come with being a teacher. On one of their breaks or doing the holiday, they should stop and look at their retirement plan and just learn about it. Figure out how it works. Figure out if teaching is even something that they’ll be staying in long enough to even recoup from that retirement plan. Learn what it is, and how they’re affected by the people who make the decisions for that retirement plan. We need more teachers who keep up with retirement issues and who can speak equitably and proactively for our profession.If you’re a teacher who enjoys reading our work and would like to tell us your story, please contact us at: info@teacherpensions.org. We can't promise to interview everyone, but we are interested in hearing how state and local retirement systems impact the lives of individual teachers, whether you are early in your career, in the middle of it, nearing the end of a long career, or looking to transition into teaching from another field.Taxonomy:

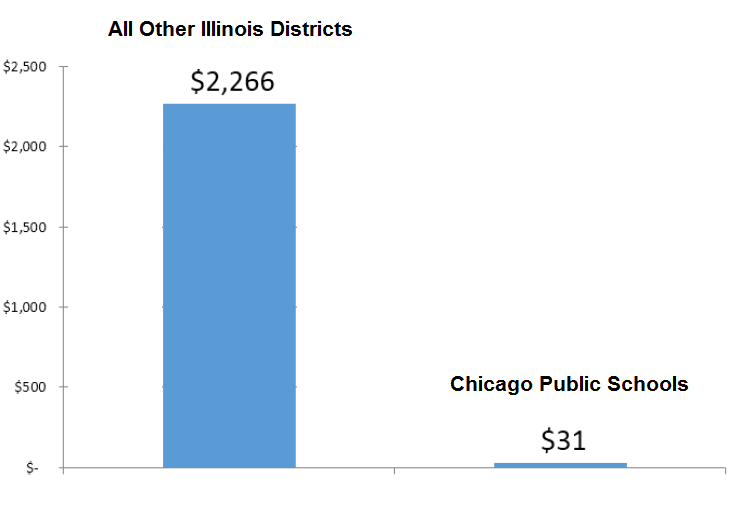

The Chicago Public Schools’ recently released its 2016 budget and it has a clear message for state legislators: Chicago needs more state pension funding. Unlike the rest of Illinois, Chicago only receives a small sliver of pension funding from the state.

While suburban and downstate Illinois school districts receive pension funding equal to roughly $2,000 per student, Chicago gets only $31 per student. That’s right, even though all taxpayers contribute the same toward the state budget, Chicago gets far less in return. On a per pupil basis, Chicago gets about 1/75th of the state pension funding as the rest of Illinois school districts.

State Teacher Pension Funding (Per Pupil)*

Source: Chicago Public Schools, “Proposed Budget 2015-16.”

Why is Chicago treated differently? A short-sighted deal made a decade ago can help explain the gap. After a school budget crisis in 1995, the state gave CPS permission to funnel tax money directly into the district’s operating budget rather than the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund (CTPF). In exchange, CPS had to cover the primary costs of the fund’s pension contributions, but only if the fund was at least 90 percent funded (which CTPF was at the time). In the short-term, it was a good deal for the district; CPS was allowed to collect $2.0 billion in levied tax revenue over 10 years while making no payments to the pension fund.

But what was initially a sweet deal has massively backfired. Over the years, pension costs have skyrocketed while state pension funding for the city has dwindled. While state legislators had originally promised an amount equal to 20 to 30 percent of the contributions made to the state retirement system, today Chicago receives less than a third of one percent in teacher pension funding.

That means Chicago residents are responsible for funding nearly all of its teacher pension debt. Unlike suburban and downstate residents, Chicago residents pay taxes that go toward the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund and the Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System. This isn’t a fair deal considering that Chicagoans only have access to the city’s schools, yet they are being asked to pay off mounting debt from both the state and the city retirement systems.

In turn, pension debt crowds out operational funding for Chicago teachers and students. This year, the Chicago Public Schools paid $634 million in pension costs, or the equivalent of $1,600 per student.

The solutions to these problems won’t be easy. Chicago Mayor Rahm Emmanuel has proposed combining the Chicago fund with the state fund and eliminate the double taxation. Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner has proposed providing Chicago with additional funding, but only in exchange for labor concessions. A better carrot would be to provide state funding in exchange for enrolling all new Chicago teachers in retirement plan that directly ties contributions to benefits and stops accruing further pension debt. Doing so would not only ensure adequate funding and transparency, an alternative plan would also actually provide teachers with adequate benefits.

*There are roughly 1.6 million students suburban and downstate students expect to enroll. Illinois will make a $3.7 billion contribution to the state Teachers’ Retirement System on behalf of local school districts (excluding Chicago), or about $2,266 per student ($3.7 billion/1.6 million). There are about 385,000 Chicago Public School students expected to enroll in the upcoming school year. The state promises $12 million in state funds for pension funding, or about $31 per student ($12 million/385,000). Chicago residents pay state income taxes that fund the Illinois Teachers' Retirement System, while also paying local property taxes that fund the Chicago Teachers' Pension Fund.

Teacher pensions protect teachers from certain risks. Teachers don't have to make their own investment decisions, meaning they don't have to worry about how much to save, how to invest, or whether they'll outlive their savings. The pension plan bears all those risks on behalf of teachers.

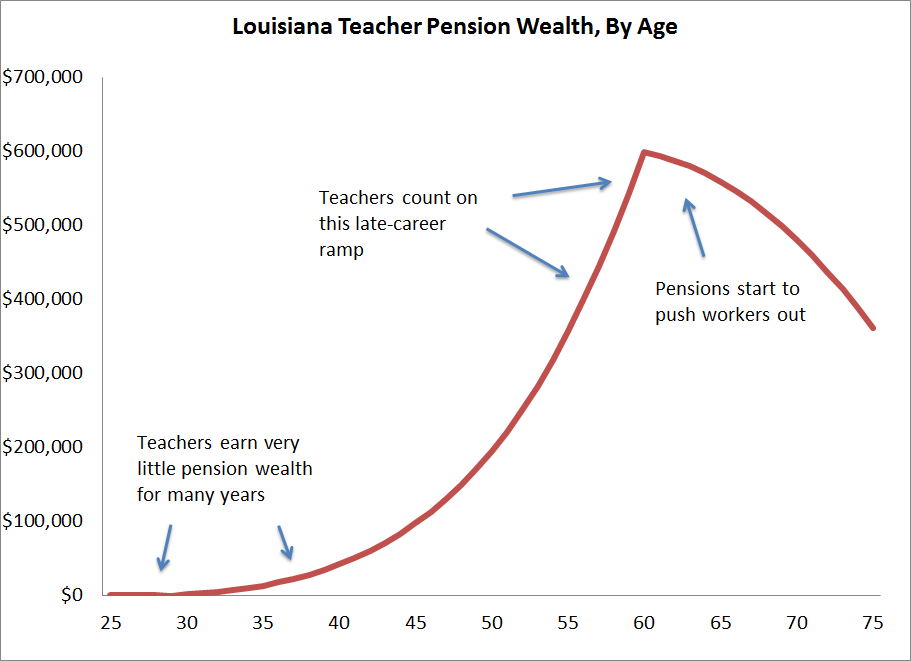

But pension plans carry another risk--attrition risk. Because pension plans are back-loaded, attrition risk is the possibility that a teacher won't stick around long enough to qualify for the larger benefits waiting for those who stay. Teachers rarely stay a full career in teaching, let alone in the same state and the same pension plan. Even if an incoming teacher may have every intention of staying a full career, her pension wealth will be tied to how long she is willing and able to stay. If life gets in the way--if a spouse wants to move, a parent gets sick, or she simply tires of teaching--her retirement wealth will suffer.

One way to show attrition risk is simply to look at how retirement benefits grow in pension plans. The graph below shows how retirement benefits accrue for a Louisiana teacher. She earns relatively modest benefits early in her career, less than what she could earn in the private sector under a cost-neutral 401(k)-style plan. Most teachers fall into this bucket--Louisiana's actuaries estimate that half of the state's teachers will leave before reaching just seven years of service. They won't get close to the much more generous benefits offered to teachers who stay for their full career. If a teacher does stay that long, her retirement wealth will more than triple between the ages of 50 and 60. But that's only if she stays that long.

This is a pretty classic case of attrition risk that exists in pension plans all across the country. But Louisiana also provides a recent example of extraordinary attrition risk.

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, the Orleans Parish School Board dismissed 7,500 employees without regard to age, years of service, or expected pension benefits. Not all of these teachers would have qualified for the significant back-end benefits promised by the pension system, but some would have. Imagine being a 50-year-old teacher in Louisiana with 25 years of experience when Katrina hit. You would have been accepting 25 years of lower pay in exchange for the promise of a solid pension in the near future. You're counting on those next ten years, when the value of your pension would triple. But when the hurricane hit, you not only lost your job, you also lost out on the opportunity to grow your pension.

Legally, the fired workers are pressing their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. They're arguing that they were wrongfully terminated after the storm and are asking for back wages. But, crucially, they are not asking for any compensation in the form of lost retirement wealth. That's because teachers don't have a right to future pension wealth accruals. Even in states with strong legal protections that restrict the state from reducing its pension formula, individual teachers can still be fired and taken off the pension wealth curve. That's another form of attrition risk.

The New Orleans story is an extreme example, but attrition risk is real and important for teachers to understand. Unless teachers know, with absolute, 100% certainty, that they're going to stay in the same pension system for their entire career, they would likely be better off in less backloaded retirement plans that offer more retirement savings earlier in their career.

Update: I added two more points worth mentioning here. One, very few New Orleans teachers stay for long enough to qualify for a significant retirement benefit. Two, Louisiana teachers are not enrolled in Social Security, meaning they're particularly vulnerable to a poor retirement system. We think all teachers should be given the retirement income protection that Social Security offers.