New Jersey teachers are still angry with Governor Chris Christie for shorting the pension fund and are now suing for $4 billion total in damages. While teachers have absolutely every right to be mad with the Governor—who after all, broke his own promise and law—teachers are also severely shortchanged by the pension system itself. Over half (55 percent) of the state’s new teachers won’t meet the minimum 10-year service requirements to qualify for a minimum pension benefit. Even for teachers who do qualify for benefits, these teachers will most likely end up paying more towards the system in contributions plus interest than what they will get back in return, losing money overall.

Christie’s pension commission proposed a fiscally responsible plan that would overhaul the current system and provide better benefits for new early and mid-career teachers. Unfortunately, however, it looks like Christie’s politics may jeopardize the chance for true reform.

The following is a guest post from Robert M. Costrell, Professor of Education Reform and Economics at the University of Arkansas.

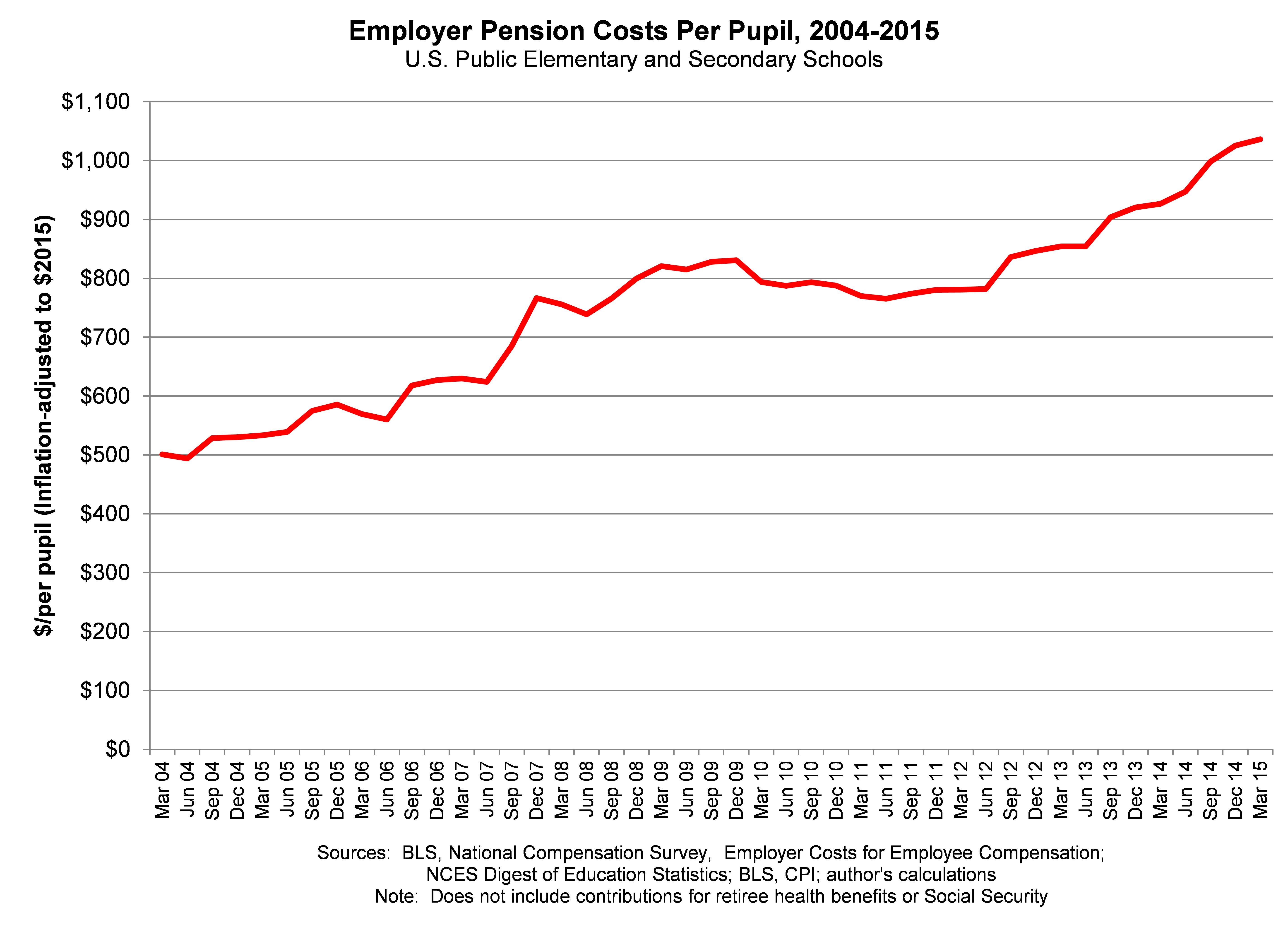

The crippling explosion of pension costs for the Chicago Public Schools has captured national attention. Although the Chicago case is extreme, the problem is widespread. Pension costs are rising across the country, even after several years of recovery from the market crash of 2007-09. A natural measure of the rise in costs is the rise in real per pupil expenditures for employer pension contributions. In this blog, I provide what I believe to be the first estimates of employer pension costs per pupil for the nation as a whole. I estimate that nationally these costs have more than doubled in the last decade, from about $500 per pupil in 2004 (in $2015) to over $1,000 today. This does not include contributions to Social Security, the costs of retiree health benefits, or the pension contributions of the school employees themselves.

In comparison to total per pupil current expenditures of about $11,600, employer pension costs represent a significant drain on resources that might otherwise have been available for classroom expenditures. Specifically, pension costs have risen from 4.8 percent of current expenditures to 8.9 percent over this period.

These estimates are constructed from two main sources of data: the National Compensation Survey of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). The BLS series discussed below allows us to calculate employer contributions for retirement as a percent of wages and salaries in public K-12 schools and the NCES Digest of Education Statistics allows us to calculate total salaries per pupil. The product of the two gives us employer contributions per pupil, and these are adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Specifically, the BLS National Compensation Survey collects the most comprehensive national compensation data in its Employer Costs for Employee Compensation (ECEC) series. The ECEC breaks down compensation into wages and salaries and various benefits, of which the relevant one here is “Retirement and Savings.” For the public schools, this cost is almost entirely contributions to defined benefit pensions. Michael Podgursky and I have previously compared these data for K-12 public school teachers with private sector professionals, and have documented the continually growing gap between them. The ECEC also provides these data for all K-12 public school employees (not just teachers), and this is the relevant figure to examine here, to derive total pension costs per pupi.

These data are reported on a “per hour worked” basis, but can be readily converted to percent of salary using the concomitant ECEC data on hourly wages and salaries. These contributions have doubled from 7.7 percent of salaries in March 2004 (the earliest data available) to 15.3 percent in March 2015.

The NCES Digest of Education Statistics provides total salaries for K-12 public schools and fall enrollment. The resulting estimate of salaries/pupil rose only slightly from $6,546 in March 2004 (in $2015, adjusted by the CPI from $5,195 current dollars) to $6,783 by March 2015 (the latter figure is derived from NCES projections for the last few years of fall enrollments and current expenditures per pupil).

Multiplying these two series together, I find that employer contributions for retirement doubled (in real terms) from $501 per pupil in 2004 to $1,036 in 2015, as depicted in the graph. Virtually all of the increase is due to the rise in retirement contributions as a percent of salary – the contribution rate, as conventionally defined by DB pension plans – from 7.7 percent to 15.3 percent.

The rise in per pupil pension costs nationally masks wide variation. In some states these costs are not rising, such as Ohio, due to benefit reductions, and Wisconsin, due to Governor Walker’s Act 10, requiring that employees split the costs with districts. In other states they are rising far more dramatically than the nation as a whole, from a few hundred dollars per pupil to over $2,000, as in Pennsylvania and Connecticut.

The causes of the rise vary by state, but they generally represent the rise in payments to amortize large unfunded liabilities. That is, the rise in employer contributions mainly represents costs that have been deferred by various means for benefits previously earned by teachers and other personnel, many of whom have long since left the schoolhouse. How to deal with this burden is much debated, but the first step is to recognize its extent.

Taxonomy:Illinois Governor Rauner recently announced plans for a sweeping pension overhaul. But in terms of teacher benefits, the proposal isn’t that structurally innovative and instead hinges upon benefit cuts for cost savings within the existing system:

- Most controversially, the plan provides existing state teachers with a choice to either accept a reduced cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) or exclude salary raises from benefit calculations. The rationale behind the choice lies mainly as an attempt to sidestep the state’s contractual protection on benefits by offering an alternative for workers to consider. But as Jesse Sharkey, from the Chicago Teachers Union, describes, the choice comes off more as “we can hit you with this rock, or we can hit you with this stick and you get to choose.” Given the State Supreme Court’s recent decision for a similar law that attempted to reduce pension COLAs and benefits, it’s unclear whether the Governor’s proposal will pass legal muster.

There are some carrots for Chicago. The state will cover the cost of benefits (normal cost) for the Chicago Public Schools. But not without some strings attached. Chicago teachers currently only pay a portion of their 9.4 percent employee contribution because the Chicago Public Schools’ “picks-up” 7 percent. The proposal does away with the pick-up, a locally decided issue, alleviating the cash-strapped Chicago Public Schools of the additional cost but skipping over the collective bargaining process for the teachers' unions. Mayor Rahm Emmanuel also isn’t thrilled about the proposal to allow Illinois municipalities—aka Chicago—to file bankruptcy. While bankruptcy would be a well-needed emergency mechanism for Chicago, politically, it’s a bitter pill for the city to even consider.

But what’s missing from the current proposal is any mention of structural pension reform for Illinois’ teachers. While the proposal includes a new hybrid plan—a smaller defined benefit with a 401k-type defined contribution account—for newly hired public safety workers, it unfortunately does not include a similar plan for teachers. Granted, the Governor is in a tough position and has already pushed for a defined contribution option for teachers and state employees (and potentially may have been more viable).

Meanwhile, the state still has no check to prevent underpayment to the Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System, which comprises over half of the state’s unpaid pension debt. By definition a 401k defined contribution plan cannot be underfunded because benefits are directly tied to contributions. The current proposal, like the previous overturned pension reform law, asks for minor fixes that tinker around the edges but leave more fundamental problems in place. In any case, Illinois' new teachers are left with the same inadequate benefits.

Chicago is between a rock and a hard place. In exchange for making its required $634 million pension payment, the Chicago Public Schools announced that it will be laying off over 1,400 staff jobs. While the proposed budget cuts won’t directly impact teaching positions, the pension system itself has been shorting teachers on their retirement benefits for years.

For all the media attention and union fury over the recent cash crunch, there been no mention about the benefits themselves, despite their severe inadequacy. According to Chicago Teacher Pension Fund (CTPF) plan assumptions, over half (57 percent) of new Chicago teachers will leave before the 10-year service requirement, meaning less than half of new teachers will qualify for a pension benefit at all.

Even for teachers who do vest or qualify for benefits, the odds aren’t in their favor. Because of post-recession pension cuts, new teachers were placed in a less-generous plan and will face negative net benefits for the first two decades of service. (Pensions aren’t like 401ks; a teacher’s contributions are completely separate from her benefits, which are calculated using a formula based on years of service and her final average salary.) A Chicago Public Schools teacher who teaches for 15 years accrues negative net benefits because the value of her contributions exceed the pension benefits she will receive in return at retirement. To make matter worse, like all other teachers in Illinois, Chicago teachers do not participate in Social Security.

Currently, the Chicago Teachers Pension Fund (CTPF) is 51.5 percent funded, but unlike the rest of the state, the Chicago school district rather than the state is responsible for paying the majority of the fund’s employer contributions. How the Chicago Public Schools (CPS)—a single school district—got wedged into paying for the city’s teacher pensions has to do with a deal made a decade ago. After a school budget crisis, the state allowed tax money to go into CPS’ operating budget rather than directly into CTPF. In effect, CPS was allowed to collect $2.0 billion in levied tax revenue over 10 years while making no payments to the pension fund.

Meanwhile, pension debt snowballed and Chicago’s taxpayers and teachers, as well as CPS, are now eating the costs. But alongside fiscal negligence, the city has lost sight of the needs of the teachers who are left to subsidize unpaid debt.

Chicago’s funding situation may be an extreme case, but the practice of passing debt onto new teachers isn’t new. Chad Aldeman and I released a report yesterday that looks at teacher pension plans over the past three decades. We found that while states boosted pension benefits throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, many dramatically cut benefits after the recent recession. The end result is that, in terms of retirement benefits, now is the worst time in at least three decades to become a teacher. For teachers in Chicago, that's all too real.

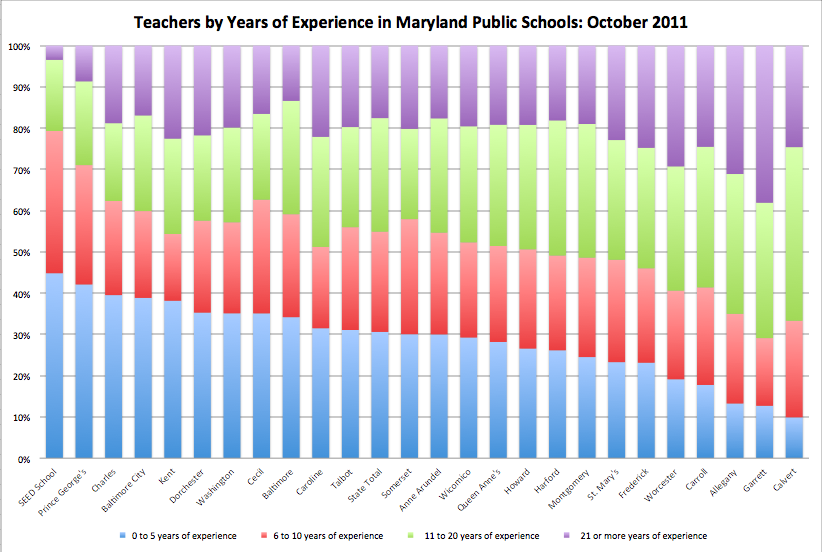

Teacher experience levels can vary dramatically state-to-state, but experience levels vary even more within states.

To show what this looks like, I’ve analyzed a dataset from the state of Maryland showing how experience levels vary by district. Data collected in the fall of 2011 found that, on average, 31% of all Maryland public school teachers had zero to five years of teaching experience. Another 24% had six to ten years of experience, 28% had 11 to 20 years, and only 18% had been in the classroom more than 20 years.

Some district workforces look very different from the state average, however. In Prince George’s County, for example, 42% of teachers had been working less than six years, with numbers in Charles County and Baltimore City County hovering near 40%. At the SEED school, a tuition-free public boarding school founded in 2008, nearly half its instructional staff was relatively new to the profession.

Other counties had much more experienced workforces. In Calvert County, for example, just 10% of teachers had five or fewer years of experience, and more than 60 percent of its teachers had 20 or more years of experience. Calvert County, a growing exurb south of Washington, D.C., has a median household income of $87,449, placing it amongst the top 20 wealthiest U.S. counties. Calvert joins Garrett, Allegany, Carroll, Worcester, Frederick, St. Mary’s, Montgomery and Harford, all districts where 50% or more of their teacher workforce has at least 11 years of experience.

These numbers reflect the range of challenges different districts face. Counties like Prince George’s, Charles, and Baltimore City employ much more mobile workforces, and thus spend more time and resources recruiting and training new teachers than Allegany, Garrett, and Calvert counties. Similarly, pension plans play out very differently amongst these two types of districts. Those with a more stable workforce are likely to reap larger benefits from the pension system, while districts with greater teacher turnover are likely to subsidize the pensions of everyone else.

A district’s teacher experience breakdown can reveal information about wide-reaching disparities, whether they be teacher turnover, resource allotment, or pension savings. Years of experience continues to persist as a key variable in teacher pension formulas, as well as salary negotiations. A revolving door of short- term teachers in some districts can end up padding the retirement benefits of others.

Taxonomy:There’s a lot of misinformation circulating around pensions. To cut through the noise, the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) and StudentsFirst released a new fact sheet that debunks the most common pension myths. Here are some highlights that the paper addresses:

- Mythbuster #1. While many assume that traditional pension plans provide all teachers with a secure retirement, the reality is only 20 percent of new teachers are estimated to stay in a single system long enough to earn full benefits. Even teachers who work a full career, but who move accross states, face steep penalities.

- Mythbuster #3. While there is the risk of investment loss in 401ks, traditional defined benefit pensions aren’t without risk. Teachers face attrition risk—or the risk that a teacher will leave before receiving adequate retirement benefits—when they enter into their state or local plan. Life's planned and unplanned events make the odds of staying in a single system slim.

- Mythbuster #5. The pension vs. 401k debate creates a false binary. Defined contributions or 401k-type plans aren’t the only alternative to traditional defined benefit plans. Other alternatives exist such as a cash balance or hybrid plans can offer teachers more secure and portable benefits.

Check out the full fact sheet to read about all eight pension myths and what the data and research really say.

Taxonomy: