Hillary Clinton is now officially running for president, and some are already predicting that Social Security will be a hot topic for 2016.

Elizabeth Warren reignited the Social Security debate when she introduced an amendment late March to the Senate budget resolution to not only ensure Social Security’s solvency, but also to expand benefits. Warren had previously introduced the idea of expansion last fall, but this time around, she has more backing—at least from her party. Nearly every Democrat supported the boost; every Republican opposed it. Mother Jones calls her move a “cool,” “tough-to-ignore 2016 issue.” Bloomberg View’s Megan McArdle wasn’t as impressed.

Interestingly, for all the talk about expansion, there hasn’t been any mention of extension to those without Social Security coverage. Currently, 6.5 million government workers hold positions that aren’t covered by Social Security. Within this pool, over a million teachers remain uncovered.

Ironically, extending coverage faces much of its opposition from the left, primarily from public sector unions. Here, unions take contradictory positions, fully embracing Social Security benefits for those who already have coverage, on the one hand, while adamantly opposing extending coverage to those without it.

Extending coverage may be less politically hip than expanding coverage, but it would improve retirement security for a significant pool of workers. The federal government has repeatedly considered extending coverage to all workers. In 1983, under the Reagan administration, Congress extended Social Security coverage to all newly hired federal workers, paving the way for the “3-legged stool” that almost all federal workers rely upon today. Recently, the bipartisan Simpson-Bowles commission recommended mandatory coverage, a move that by itself could reduce Social Security’s long-term shortfall by eight percent and extend the trust fund’s solvency by two years. Additional reports from the Social Security Administration and the Government Accountability Office have confirmed similar numbers. Extending coverage would also better distribute the burden of Social Security’s legacy costs, which comes from the first beneficiaries getting more in benefits than what they contributed.

Expansion may be a better political talking point than extension, but extending coverage to all workers would provide public sector workers with better benefits, while simultaneously distributing the legacy burden more evenly across all workers and improving Social Security’s long-term solvency. Because eventually, it’ll be time for each of us to retire.

Taxonomy:- In honor of Equal Pay Day, the symbolic day in which the average woman finally catches up to what the average man earned last year, labor unions and pension advocates have taken to Twitter to proclaim how great pensions are for women. Not so fast. In many ways, women are actually worse off under defined benefit pension plans than they would be under more portable plans.For teachers—over three-quarters of whom are women—state teacher pension plans disadvantage females in several ways:

- Women who leave the teaching profession before serving a full career—either to change professions, rear a family, or other personal reasons—are shortchanged. Women who leave before vesting will not receive a pension and those who stay on for less than a full career will receive minimal benefits. Because pension wealth accrues unevenly in favor of those who stay for thirty-plus years, all workers who stay less time, including and especially women, lose out.

- Women are especially dependent on Social Security, but about 1 million teachers are not covered by Social Security at all. Applying the same demographics of all public school teachers to just this population, that makes about 750,000 female teachers who lack the guaranteed retirement and disability benefits given to all other American workers enrolled in Social Security.

- The female-dominated teacher workforce typically participates in pension plans with other male-dominated workforces with higher salaries. In practice, this means shorter-serving, lower-paid teachers (mostly female) are forced to subsidize the retirements of other groups of workers such as principals and school administrators (mostly male). This can also include other groups of state and local government employees.

Americans have certainly come a long way in the past few decades: the pay gap between men and women has fallen from 36 cents in 1980 down to 15 cents as of 2018. Despite the narrowing gap between men and women, the disparity in compensation persists, and it carries over into retirement. Current pension plans aren't doing enough to provide retirement security to all teachers. The New York Times had a big story yesterday on how Wall Street investment fees wiped out $2.5 billion in investment gains for New York City pension funds. The fees ate up nearly 97 percent of the investment gains over the last 10 years, leaving just $40 million in gains for the retirement fund for teachers, police officers, and firefighters. The story gained widespread attention in the financial world and even from the American Federation of Teachers' Randi Weingarten.

The whole thing started with a bizarre presse release from New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer. Bloomberg's Matt Levine takes a further look and tries to do some back-of-the-envelope math to calculate the percentages the funds paid.

But if you read all this, what's startling is just how little anyone knows about how the pension plan investment decisions are made, what sort of fees they pay on those investments, and how their investments perform over time. The city's comptroller had to run an internal study to find out, and even he could barely make heads or tails of it!

The same is true if you try looking at individual pension plans. I pulled up the latest investment portfolio update from the Teachers' Retirement System of the City of New York and found a long list of investment managers with Wall-Street-y names. All told, NYC teacher pensions are invested with 270 (!) different "Pension Fund Investment Managers" with names that run from "Acadian" to "Yucaipa Corporate Initiatives Fund II, LP." They list another 25 "Diversified Equity Fund Investment Managers." Why do they need all these plans? What do these plans charge in fees? The answers to those questions aren't readily apparent.

If you're a teacher in New York City, you might want to know these things. You might even want your union representatives to watch over them and ensure that your retirement system was getting the best investment value for the lowest fees. But instead, teacher union representatives are busy playing politics with the pension fund investments, seeking to trade one set of unfriendly hedge funds for another set of friendlier hedge funds. The AFT's official position on pensions touts its political oppostion but doesn't mention anything about pension plans' fiduciary responsibility to its members, let alone ensuring that retirement systems work well for teachers.

The real scandal is the lack of transparency on pension fund investments and the fact that no one, not the comptroller, and not the unions, are looking out for pension plan members.

Taxonomy:Last In, First Out (LIFO) policies prioritize seniority when a district must make reductions to its teacher workforce. The last teachers hired are the first ones with pink slips.

Unfortunately, this practice of favoring seniority at the cost of early career teachers extends to pensions, albeit in a slightly different form. More often than not, benefit cuts fall on new teachers.

Many states protect public sector pension benefits with strong, near ironclad legal rules that make it tough-to-impossible to reduce benefits for existing workers. Many state constitutions and statutes explicitly protect the existing, and sometimes even future unearned benefits, of teachers. These protections are good for teachers already in the system, but when tough budget times hit they often leave states with no other choice but to cut benefits for those just joining.

States may trim other benefits for current workers, reducing cost-of-living adjustments, or COLAs, which adjust benefits for inflation. But even still, states continue to struggle with gargantuan underfunding and look for other avenues for cuts. A few headstrong legislatures, such as Illinois and New Jersey, are trying to reduce or freeze benefits for existing workers despite strong legal protections. Illinois is now in the throes of a legal battle over its changes. It’s unclear whether New Jersey’s proposal will move forward. Rhode Island may be an exception.

So in order to avoid the political and legal headache of trying to cut benefits for existing workers, states typically take the easier path and create new “tiers” or modified versions of a plan with lower benefits for new teachers. All new teachers hired after a specific date are put into the different tier with reduced benefits, while senior teachers hired before the date remain in the better, more generous plans they were hired into. Over 40 states place teachers in separate tiers by their hire date according to the Urban Institute’s state report card.

Illinois provides an illustrative example. In 2011, Illinois passed legislation creating a “tier 2” plan for new teachers. Tier 2 offers worse benefits for new teachers: it has a higher minimum service requirement (up from five to 10 years, making it more difficult for new teachers to qualify for a minimum benefit), a higher normal retirement age (meaning teachers have fewer years to collect pension payments over a lifetime), a less generous pension formula (calculating the final average salary from the last eight years of service instead of just four), and a lower COLA. The graph below comes from a report by Robert Costrell and Mike Podgursky, and looks at the net pension benefits for Illinois teachers before and after cuts. The top, dotted, curve shows benefits for existing teachers hired before 2011. The lower, solid curve applies to new teachers hired after 2011.

The gap between the plans is large. Existing teachers are protected, while new teachers bear the brunt of the reform cuts. For new teachers, pension wealth is actually negative for the first 25 years a new teacher teaches under tier 2. Despite lower plan benefits, new teachers still need to contribute the same percent of employee contributions as more senior teachers, reducing overall net pension benefits even more.

Net Pension Wealth for Illinois Teachers

Source: Robert Costrell and Michael Podgursky, “Reforming K-12 Educator Pensions: A Labor Market Perspective,” TIAA-CREF Institute, February 2011. Shows pension wealth accrual, net of employee contributions, adjusted for inflation, for a 25-year old entrant.

Compounding the LIFO effects between tiers, the traditional pension structure inherently favors late- over early-career teachers. Unlike other retirement savings plans, traditional pensions aren’t directly tied to a teacher’s contributions. Instead, pension formulas largely hinge on two main factors: a teacher’s time in the classroom and their average salary just before retirement. As a result, the bulk of a teacher’s retirement wealth is earned at the back end of her career, if she makes it that far.

There’s a significant chasm between what early- and late-career teachers earn in retirement benefits. In New York City, a public school teacher who begins at age 25 earns roughly $3,500 per year for the first 20 years she teaches. If she works for an additional 18 years, she earns $30,000 per year during these later years. In Illinois, a teacher who begins at age 25 and works for 10 years accumulates $28,000 in overall lifetime benefits; a teacher with 35 years peaks at $1.3 million. Needless to say, pensions aren’t evenly distributed.

But to be clear, while policy recommendations for revising Last In, First Out layoff decisions generally means tying a teacher’s job to her performance, adequate retirement benefits should be offered to all teachers as part of an attractive compensation package. All teachers deserve secure retirement benefits, period.

States need to pause and consider how cuts unevenly impact teachers. Simply cutting benefits for new hires can’t continue forever.

In the upcoming months, TeacherPensions.org will be releasing a report that looks at changes that state pension plans have made over the past few decades. Check back here for our analysis of those cuts and the impact on the teaching profession.

Taxonomy:In what counts as big news in the pension world, President Obama last week tentatively endorsed changing the retirement plan offered to military members. Under the proposal, military service members would shift from an all-or-nothing pension plan to a “hybrid” model combining a less generous pension plan, a 401k-style defined contribution plan, and cash bonuses paid out at various career milestones as retention incentives.

There are three important political developments here. First, the big one: President Barack Obama is now on record in favor of pension reform. The final report from the Military Compensation and Retirement Modernization Commission made it clear they supported reforming the pension plan because it was good for workers. This is a tremendously important signal within a broader context where pensions are often treated as a third rail> political issue that cannot be touched.

Second, it’s a sign that the politics of pensions may be changing as people start to realize that pension systems with a few big winners at the expense of lots of small losers is not a good retirement policy. All workers need a path to a secure retirement, not just a select few. But with less than 20 percent of the military’s enlisted personnel staying the requisite 20 years to qualify for a pension, it’s clear that the current pension plan is not providing sufficient retirement savings to the vast majority of the military.

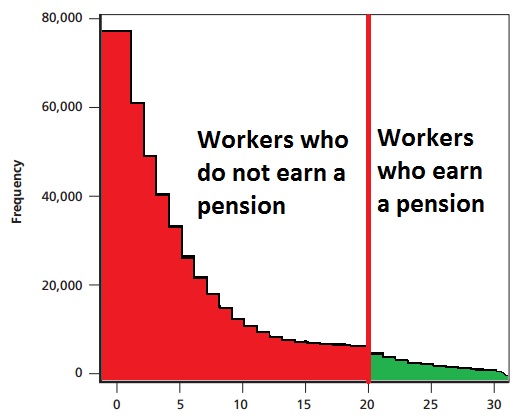

The chart below, modified from a RAND report commissioned by the military, shows a profile of the existing military enlisted workforce. The vertical bar at 20 years represents the pension requirement. Workers who stay less than 20 years get no retirement benefit at all, while those who do qualify for a pension worth at least 50 percent of their salary. The majority of workers have five or fewer years of experience, and only a fraction of workers even approaches the 20-year mark.

Teachers are in a similar albeit not as extreme predicament. The teaching workforce has relatively high early-career turnover that flattens out over time. Teacher pensions are not all-or-nothing, but only about half of new teachers will qualify for some pension. The rest leave with only their own contributions, sometimes with interest. Because teacher pension benefits are heavily back-loaded, the Urban Institute estimates the median state requires teachers to stay at least 24 years before they hit the “break-even” point where their pension is finally worth more than their own contributions plus interest. Less than one-quarter of new teachers will reach that point, and less than one-in-five new teachers will remain in a pension plan long enough to reach the normal retirement age set by state lawmakers.

The question facing pension advocates is how long they want to protect this unequal and unfair system. Will they keep defending pension plans where a few teachers get solid retirement benefits at the expense of the majority? Or will we move to retirement systems that provide all 3 million teachers with a solid path to retirement?

The third political shift worth noting is that data are busting the myth that pensions are good for worker retention. For example, the graphs showing how little the military’s current pension system affects worker retention are striking. In contrast to theoretical arguments on pensions and retention, the best available data suggest pensions are not a strong retention incentive for most teachers either. Any efforts to dramatically alter retention rates must aim at the large group of workers who leave early in their careers. Back-loaded pension benefits simply cannot alter the behavior of most workers.

President Obama’s actions signal a small shift in the political winds on pensions. As evidence mounts showing how poorly structured pension plans fail to meet the needs of today’s workforce, let’s hope more politicians make it a trend.

Taxonomy:Imagine not getting any retirement benefits from your employer after working for almost a decade. Or having to wait 25 years before your retirement savings are finally worth at least your own contributions plus interest.

Yes, it’s April Fools’ Day. But no, this isn’t a gag. This actually happens to teachers across the country.

Current pension plans disadvantage early- and mid-career teachers. In most states, this includes all teachers who stay less than 25 or 30 years in a single system. Over half of new teachers won’t meet the minimum vesting or service requirements to qualify for any pension, according to state pension plans’ own assumptions. Even for mid-career teachers who remain in the classroom for longer, but don't retire right away, the median state requires teachers to work for 24 years before receiving a positive return or come out ahead on the value of their employee contributions and interest. To make matters worse, in 15 states, teachers don’t qualify for Social Security for their time in the classroom, further exacerbating their retirement uncertainty.In response to the 2007-9 recession, states are now placing even more obstacles before teachers. Twelve states increased their minimum service requirements, making it more difficult for new teachers to qualify for a minimum benefit. Employee contribution rates and the normal retirement age are rising, making it less likely that a new teacher will get a pension worth more than her own contributions plus interest.Unfortunately, states and local plans have played these tricks on too many teachers for too long. It’s time for states to stop fooling around with teacher retirement security and provide adequate benefits for all 3 million of them.Taxonomy: