The National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) released a report grading each state’s teacher pension system. Based on data collected since 2008, NCTQ grades each state’s teacher retirement plan on three components:

- Plan funding and sustainability. Collectively, state pension plans face a $1.4 trillion shortfall, with teacher pensions alone accounting for $500 billion in unfunded liabilities. For every dollar contributed to state teacher pension plans, an average of $.70 goes toward paying down the pension debt (rather than benefits for current teachers). NCTQ urges states to more responsibly manage their pension debt.

- Flexibility and portability. Teachers who leave before vesting do not qualify for benefits, and over half of teachers won't vest into their state's pension system. Non-vested teachers receive a refund on their contributions and sometimes interest, but rarely receive any portion of their employer contributions. NCTQ recommends a vesting period of three years or less and that plans allow non-vested teachers to keep a portion of their employer's contributions.

- Neutrality. Pensions benefits are heavily back-loaded where teachers accrue substantial benefits in their later career years. NCTQ recommends that states design plans that allow teachers to accrue benefits uniformly for each year of work, treating early and later career teachers equitably.

Amongst the high performers, NCTQ graded Alaska and South Dakota with top grades:

Alaska was the only state to earn an “A” grade. Alaska provides teachers with a fully portable, defined contribution retirement plan. The plan allows teachers to vest immediately on their own contributions. Vesting on employer contributions is graduated (25 percent after two years, 50 percent after three years, and 75 percent after four), with full vesting after five years.

South Dakota received a “B+” grade for its low vesting requirement (three years) and portability. Teachers who leave before vesting can withdraw their contributions, interest, and a 50 percent match on employer contributions

On the other hand, amongst the low performers:

Mississippi received a failing grade. Poor-funding, high vesting requirements (eight years), and high employee and employer contributions rates make Mississippi a poor system for teachers and taxpayers.

Overall, state teacher retirement plans received an average grade of a “C-.” For more information or to read an individual state's report, see here.

I've written before about how bad Illinois' pension plan is for new teachers. But you don't have to take my word for it. Read Dick Ingram, the Executive Director of the Teachers' Retirement System (TRS) of the State of Illinois, explaining in his own words how teachers hired after January 2011 (enrolled in a pension plan called "Tier II") lose out to all those who came before (those who participate in a more generous plan called "Tier I"). It's quite remarkable for its candor:

Tier II is designed to help solve the financial problems faced by TRS and the other systems by reducing pension benefits for these new members. Lower pensions means reduced long-term costs for the state.

If Tier II is left alone, it will accomplish its mission. The $61.6 billion TRS unfunded liability will shrink over several decades and eventually be eliminated because the state will pay less to the ever-growing number of Tier II members. In fact, at some point in the future, we estimate that Tier II members actually will help create a surplus of funds for TRS that effectively could eliminate the need for any state government contribution to the System.

But the core of Tier II – the reduced benefits structure – is a problem the Teacher Recruiting and Retention Task Force will review. The benefit structure is unfair to all Tier II members. Right now, a Tier I member’s pension costs roughly 20 percent of an active member’s salary. Because of the benefit reductions in Tier II, a Tier II member’s pension is worth just 7 percent of an active member’s salary. However, by law, active Tier II members of TRS, like me, pay the same 9.4 percent salary contribution to the System that active Tier I members pay.

What all this means is that Tier II members are paying the entire cost of their pensions plus an extra 2.4 percent to TRS. That extra 2.4 percent subsidizes the pensions of Tier I members.

Like other Tier II members, I’m happy to help out, but I’m not really too thrilled with paying for my entire pension and paying extra to subsidize somebody who is paying less than half the cost of their pension. I like all of you very much, but this is a matter of equity for Tier II members.

And someday this subsidy may be declared unconstitutional, which threatens the revenue stream that is designed to eliminate the System’s unfunded liability. We may see a scenario where Tier II members argue in court that the subsidy we pay is really an extra income tax – a tax that only we have to pay. That would be unconstitutional.

Hat tip to Mark Glennon at WirePoints. Read the full text of Ingram's letter here.

(Update: As a reader pointed out, Ingram's future projections assume all the state's actuarial assumptions are correct, investments return a compound interest rate of 8 percent, and the state upholds its funding commitments. If those assumptions prove incorrect, the state may be forced to create a new, even worse plan or raise contribution rates further.)

Taxonomy:State pension plans are shouldering a collective shortfall of $1.3 trillion dollars in unfunded liabilities. While the recent recession took a large toll on plans, however, other factors like inadequate contributions are also to blame.

The Center for Retirement Research (CRR) recently released a report quantifying the factors that led to state and local plan underfunding. The CRR tracked five specific factors in 150 public plans from 2001 to 2013: 1) investment returns; 2) plan contributions; 3) actuarial assumptions; 4) benefit changes; and 5) other assumption changes. Using this data, CRR looked at how each of these factors impacted a plan’s unfunded liability over time.

Low investment returns and inadequate contributions were the top two factors impacting a plan’s unfunded liability. Plans faced two financial crises over the past two decades, once in the early 2000s when the dot-com bubble burst and again after the financial downturn in 2007-9. But this doesn’t tell the whole story. While the recession hurt all plans, poorly funded plans that were skimping or skipping contributions fell much further than well-funded plans. Overly rosy investment assumptions also didn’t help.

A good example is the New Jersey Teachers Retirement System (TRS). New Jersey hasn’t made adequate contributions to cover the annual cost of benefits, let alone the plan’s unfunded liability, since the 1990s.

Low investment returns impacted New Jersey’s unfunded liability by over 60 percent. But poor management in the form of missed and cut contributions played a key role in New Jersey’s current status, changing the state’s underfunding by almost half. Overly optimistic demographic and investment assumptions also increased the unfunded liability. The chart below shows how much these and other factors like increasing or decreasing benefits or changing assumptions (i.e., interest smoothing or gradually adjusting interest rates incrementally)—impacted the New Jersey Teachers’ Retirement unfunded liability.

Factors Impacting the New Jersey Teachers’ Retirement System’s Unfunded Liability, 2001-2013

Source: Alicia H. Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubry, and Mark Caferlli, “How Did State/Local Plans Become Underfunded?”, Center for Retirement Research, 2015. The graphs show the percentage of overall change in the aggregate Unfunded Actuarial Accrued Liability (UAAL).

For most plans, the main factor driving unfunded liabilities were low investment returns that fell short of what plans were expecting. But another serious factor was failing to make adequate contributions, especially for the worst-funded plans (like New Jersey). While missed contributions accounted for close to half of New Jersey’s poor funding, for a better-funded plan like Georgia, missed contributions only impacted the plan’s unfunded liability by 18 percent.

It’s clear that states need to change how they are managing their public retirement plans. While stock market returns are unpredictable, states should be more responsible on the things they do control, like good funding practices.

Taxonomy:TNTP has been following retirement options for charter schools in a cluster of states, and their preliminary findings are fascinating. Rather than relying on the state’s pension system, several charter schools are offering teachers portable retirement benefits and/or reallocating funds for salary increases or other forms of compensation.

Sixteen states allow charter schools to choose whether they participate in the state’s retirement system. Within a subset of seven states TNTP is following, over half of charter schools chose not to participate in their state’s retirement system.

Instead, these charters are finding innovative alternatives to traditional pensions. The schools recognize that current teachers are increasingly mobile and offer teachers portable benefits: 401(k) or 403(b) defined contribution plans. What’s more, all of the schools reported minimum service requirements of five years or less—with half of schools offering immediate vesting or within one year of employment. In a separate study conducted by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, Amanda Olberg and Michael Podgursky looked at alternative retirement plans offered by charter schools in several key states where participation in the state system was optional.

Alternative Retirement Plans Offered by Charter Schools

Source: Amanda Olberg and Michael Podgursky, Charting a New Course to Retirement: How Charter Schools Handle Teacher Pensions, Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2011.

While a number of schools offer no plan, many chose to offer teachers defined contribution plans like a 401(k) or 403(b). In the Fordham study, 43 percent of schools chose to offer teachers a dollar for dollar match on their contributions and 18 percent offered a percent on the dollar. For example, a school might match an employee contributions dollar for dollar up to 4 percent of a teacher’s base annual salary, or they might offer a 50 percent match up to 4 percent of the teacher’s base annual salary. The most common dollar for dollar employer contribution match rate was 4 to 6 percent, but matches ranged from 2 percent to a graduated 15 percent (for employees who worked 15 or more years at the school).

Opting out of the state retirement system also means that charters have more flexibility for reallocating retirement funds into other forms of compensation. TNTP spoke with one school that raised teacher salaries five percent higher than surrounding districts, giving that school a competitive edge to recruit top talent. Another charter network gave teachers a set amount of flexible money to pay for benefits (such as optional healthcare, vision, dental and required disability and life insurance). Anything not spent on benefits was given back to teachers as a lump-sum check at the end of the year: additional cash teachers could pocket and/or invest however they chose.

Teachers are increasingly mobile and need portable benefits that they can take with them wherever they go. Policymakers should keep an eye out on charters and what they’re doing to innovate not just in the classroom, but also in teacher retirement.

The median U.S. worker has less than five years of experience at his or her current job. And teachers are no exception. Over the decades, teachers, like the rest of the American workforce, have become increasingly mobile. Unfortunately, teachers, who are the largest class of workers with a college degree, are still offered the retirement benefits as if they were a much more static workforce.

Fitting with national trends, teachers frequently move across state or district lines and change positions within and across sectors. The most common number of years a teacher has served in the profession has dropped from 15 years in 1988 to five years today. A person might start out as an elementary teacher and then move to curriculum publishing, or likewise might start out as an engineer and switch careers to teach. Or a teacher might teach in one state for a few years, then follow their spouse to another state and teach there.

Almost all teachers must participate in a state or district pension system. Traditional pensions, however, were designed decades ago, in some cases a century ago, and generously reward teachers who stay in the classroom for 30 or more years, while disadvantaging those who stay for less. Service requirements, known as “vesting” rules, require teachers to stay a certain number of years in the classroom in order to qualify for a pension. Most states have a 5 year requirement, while an increasing number of states have increased their vesting requirements upwards of 10 years. This means that a teacher can stay in the classroom for up to nine years and leave with nothing beyond a refund of her own contributions, sometimes with interest. Over half of teachers will not meet their state vesting requirements.

For teachers who move across states, the penalties are just as steep. Pensions aren’t portable, so a teacher who moves can’t just bring her pension or service years with her. Once she moves, her previous years spent teaching are erased and she starts back at square one with zero years of service on the clock. Technically, a teacher who has prior teaching experience can “buy” service years. But this turns out to be an expensive and pretty bad deal.

Put this all together, and traditional pensions simply aren’t cutting it for teachers. Teachers need stable retirement benefits that they can take with them wherever they go. Social Security provides exactly this: benefits are a low-risk, inflation-protected, lifetime annuity that move with a worker from job-to-job. Many teachers have Social Security coverage, but over 1 million (or 40 percent of the teaching force) lack coverage. States can and should improve their own retirement benefit offerings to teachers, but this still won’t replace Social Security. Teachers can benefit by diversifying their streams of retirement income, one of which should include Social Security.

We recently released a report that argues that teachers at all experience levels have much to gain from Social Security. While Social Security is not sufficient as a stand-alone benefit, extending coverage to teachers would be a positive step in the right direction.

To learn more about teachers and Social Security, read our new report and the condensed PowerPoint version.

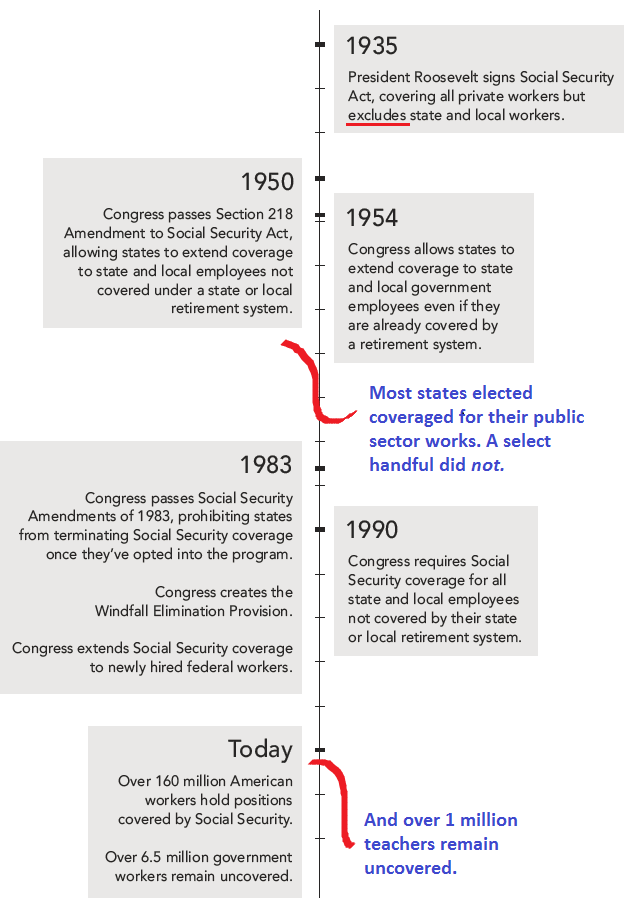

Teachers have a complicated past with Social Security. We made a timeline that boils down the key dates in Social Security’s history that have impacted teachers.

Teachers, along with other public sector workers, weren’t originally included in the 1935 Social Security Act. In the 1950s, Congress gave states the opportunity to extend coverage. Most states decided to give their public sector workers coverage, but a select handful of states chose not to.

While Congress has mandated Social Security coverage for all public sector workers not covered by a retirement plan, this does not affect teachers. Teachers are technically covered by their state pension plan—even though over half will not actually qualify for any benefits, and those that do qualify, will actually lose out on their own contributions. These teachers remain overlooked by states and the federal government and are at risk of inadequate savings at retirement.

To learn more about teachers and Social Security coverage, read our new report and Powerpoint.

Taxonomy: