There's a strange paradox going on in public pension funding.

On one hand, pension plan assets are higher than ever. Rising stock markets--the S&P 500 has tripled since reaching a low in March 2009 and over the last 10 years, the largest public pension plans have earned an average return of 7.45 percent, broadly in line with the median long-term goal of 8 percent--have boosted pension plan coffers to the highest level of assets they've ever had. Nationwide, state and local pension plans have collectively accumulated $3.7 trillion, an astonishing sum of money.

On the other hand, pension funding ratios remain virtually unchanged. According to the latest figures, pension plans have not made much of a dent in their long-term unfunded debt. How could this be? A recent article from The Arizona Republic summarizing a Moody's Investors Services report helps illustrate why:

1. Insufficient Contributions: State and local governments have a tendency to under-fund pensions even during good times. But economic crashes hit pensions at the same time they hit state and local governments. When faced with the choice of contributing to under-funded pension plans or paying for current services like schools, roads, and prisons, politicians tend to opt for the latter.

2. Compound Interest: When governments delay contributions into the future, they're inevitably raising the long-term cost of the debt. Like a creditor paying off only their minimum balance, states have pushed many of their costs out to some future day of reckoning.

3. Less Aggressive Assumptions: Many states responded to recent recessions by adjusting their investment assumptions down from 8.25 to 8 percent or from 8 to 7.5 percent. It's important and a good policy for states to recognize a more modest investment return, but it forces them to admit much higher liabilities than they previously assumed.

4. Actuarial Miscalculations and Demographic Changes: Pension plan valuations depend on assumptions about a host of factors like how much employees will earn, how long they'll stay, how long they'll live in retirement, etc. Things like higher-than-expected pay raises, higher retention rates, and longer life spans all add liabilites to a pension plan. States have tended to err on the side of under-estimating their actual future costs.

The end result is that pension plans are in almost exactly the same shape they were during the worst of the recent recession. Pension plans were counting on rising stock market values to overwhelm these factors, but so far that bet hasn't panned out. The horrifying truth is that the current bull market--which has already been one of the best periods in modern history in terms of both duration and strength--has been unable to significantly restore pension valuations. That's a scary reality for taxpayers, retirees, and current workers, who must hope markets continue to rise. If not, and until we see more systematic reforms, we may see another round of contribution increases and benefit cuts.

Update: Bloomberg reports on a miniscule uptick in funding ratios. Using the latest available data, it found that, "the median state system last year had 69.3 percent of the assets needed to meet promised benefits, up from 68.7 percent in 2012." State pension plans need continued strong performance in the stock market for funding levels to improve more rapidly.

Taxonomy:While Teach for America (TFA) teachers are working to close the achievement gap, most are also losing out on core retirement benefits like a pension and/or Social Security, creating a gap in retirement security.

Teach for America has produced close to 40,000 teachers over the past decade and continues to grow rapidly. Corps members serve a two-year commitment in low-income urban or rural schools (disclosure: I was a TFA corps member and taught in Baltimore for three years). They work as full-time teachers and receive salary from their district employers and presumably retirement benefits from their state or local system.

Although TFA teachers are just a drop in the bucket compared to the entire teaching pool, the program gets frequent national attention, especially about its retention and effectiveness numbers. A recent study from the University of North Carolina examined retention and effectiveness amongst early-career teachers in the North Carolina public schools, dividing teachers by their preparation program. The study found that TFA teachers, while only comprising a small fraction (0.5 percent) of all North Carolina teachers, outpaced all other teacher preparation programs in teacher evaluation ratings and their added impact on student achievement. TFA teachers, however, had the lowest retention rates. Less than a third of North Carolina TFA teachers stayed for 3 years and only 10 percent stayed for 5 years.

While most TFA teachers may not realize it, almost all are losing out on retirement benefits for their time in the classroom. Consistent with national trends, TFA teachers are not staying in the classroom long enough to meet state service requirements or vesting requirements for a pension (to be clear, TFA is simply too small to be the cause of these national trends). Most states require a 5 to 10 year vesting periods. Nationally, almost two-thirds (60.5 percent) of TFA teachers continue working as public school teachers beyond their two-year commitment, but nearly three-quarters (72 percent) of all TFA teachers will leave the classroom before five years. In North Carolina, 90 percent left without retirement benefits despite the state’s decision to keep lower service requirements at 5 years rather than 10 years. In several states, TFA teachers are not covered by Social Security because of state prohibitions against public school teachers and/or public sector workers; teachers in these locations lose out on pension and Social Security benefits.

Recently, Teach for America announced it would pilot a new program aimed at increasing preparation and retention amongst their teachers. The decision marks one of the biggest policy changes in its program history. In making this historic shift, the program should also consider that a significant portion of its members have lost out on core benefits, and teachers, as working professionals, need adequate pay and retirement security. Salary and benefits are obviously not the reason teachers teach, but they are important levers that stakeholders need to consider for strengthening recruitment and retention.

Chris Lozier has served as CFO and COO of several education organizations, including the 2,500-student Chicago CMO Civitas Education Partners. His obsession for data analytics is deeply rooted in his experience serving underwater in the 1990s as a nuclear engineer and submarine officer.

There are two broad ways we might better inform the American public and, more importantly, the pensioners to whom critical promises have been made. One way would be to assess factors that threaten the sustainability of these pensions but which are not already accounted for by the pension accounting and actuarial assumptions on which almost all reporting, conjecturing, and debate are based (e.g., states’ financial health, churn rates among teachers, and others…more on that later).

Another way to move the conversation forward would be to simply tell the story of pension data in a way that might make more sense to non-accountants, non-actuaries, and other laypeople who don’t get paid to understand the complicated math, the accounting magic, or the inconsistent policymaking. This category comprises most everyone.

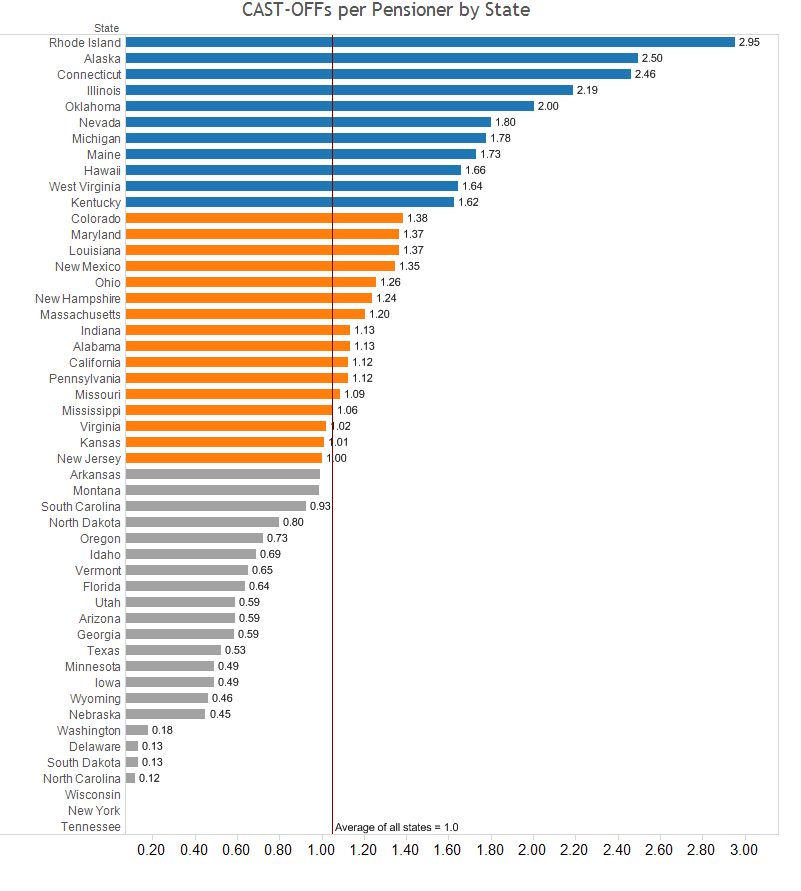

One simple metric might accomplish the latter and help describe states’ relative pension challenges in a way that is easier for most of us to understand and appreciate. Rather than talking about funded percentages or by how many billions of dollars a state’s obligations exceed its assets, what if we could measure a state’s funding shortfall in terms of current employees?

It turns out we can with the help of a few basic numbers from the Boston College Center for Retirement Research and the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2012 Survey of Public Pensions. Using unfunded actuarial accrued liability (UAAL) from the former and covered payroll and membership data from the latter, we can arrive at an understandable metric for each state:

The number of average pension member salaries needed to close the gap

and fully fund the average obligation made to all pension members

I’ve dubbed this “current average salaries to obtain full funding per pensioner,” or CAST-OFFs per Pensioner.

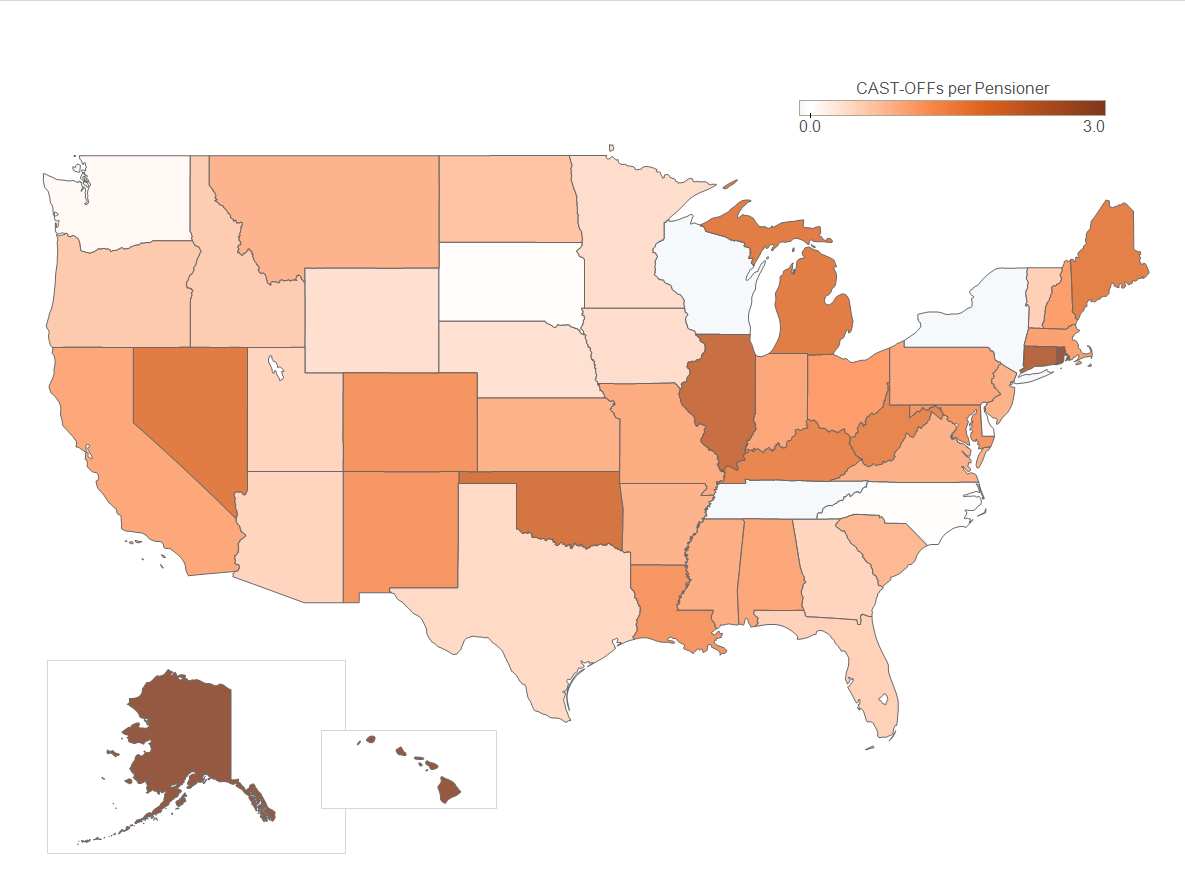

The map below shows CAST-OFFs per Pensioner by state. The darker states reflect a higher number of CAST-OFFs and a worse financial position.

What does this map tell us in plain English? In Illinois, for example, the average FY12 payroll per active pensioner was about $50,000. Meanwhile, the state-administered plans were underfunded by about $110,000 per plan member. Therefore, Illinois’ average pension debt per plan member is as large as the salaries of 2.2 average active pensioners. Put another way, the average Illinois state pension fund member could have the promise that’s been made to him or her fully funded if one average active member would contribute his or her entire salary to the pension fund for 2.2 years.

The state-by-state coloring of this map will not significantly differ from similar maps describing the funded status of states. However, these numbers can help interested observers better appreciate “how far behind” states are in being equipped to make good on their promises simply by putting this shortfall in terms that carry greater intuitive meaning.

This method has the added benefit of incorporating a normalizing effect by accounting for the average salary of active pensioners. It would be easy to think, “if current salaries are higher then, all else being equal, the liability will end up being higher.” This is true but this should be accounted for in the UAAL. By bringing average payroll into the denominator, we’re effectively saying the obligation relative to the current cost of the active pensioners is less in this scenario.

For active pensioners who may be years away from taking money out of the pension system, a feel for how many average salaries their state has fallen behind might raise awareness and even lead to greater action from within.

--Chris Lozier

Taxonomy:Public sector unions praise Social Security. Except they don’t want it for all of their workers.

The National Education Association describes Social Security as the “cornerstone of economic security,” and Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers, describes it as “the healthiest part of our retirement system, keep[ing] tens of millions of seniors out of poverty [which] could help even more if it were expanded.” Last year, the Alliance of Retired Workers, an affiliate of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) even made the Social Security Administration a blue and white frosted birthday cake for its 78th anniversary.

But not all local government workers have Social Security. Over 6 million public sector workers are not covered by Social Security, including about 1.2 million public school teachers; in 15 states, public sector workers do not pay into or receive benefits from the system. If you were to ask, however, whether all state and local workers should have Social Security, most public sector unions would adamantly reply, no.

Why do unions hold such conflicting views on Social Security? The primary reason—pensions. Unions fear that extending Social Security coverage will signficantly cut into existing pensions, which are more generous to full-career workers in states that do not offer Social Security coverage.

However, public pensions in states without Social Security coverage offer more generous benefits because they were designed as a stand alone benefit. Coordinating Social Security with state pension plans would likely result in equal or better retirement benefits overall for more teachers, especially those who do not qualify or receive much of a pension. What’s more, unlike pensions, Social Security is portable and does not penalize workers for moving across state lines. While the politics around teachers and Social Security coverage are at odds, Social Security could be a core part of improving teacher retirement plans. In particular, Social Security could provide a floor of retirement security for early career teachers who often leave the system with nothing.

We’ll have more to say on this topic in the coming months.

Taxonomy:My colleague Jason Weeby asked me what I thought of a Michigan legislator's plan to close the state's current retirement plan and instead offer all new teachers a 401(k)-style plan. I had two:

1. "401(k)" is occasionally thrown out by pension advocates as a scary alternative to traditional pension plans. But not all 401(k)s are the same, and they could be structured in a way that would offer teachers greater portability than current pension systems while placing more teachers on a path to a secure retirement.

The term "401(k)" comes from the federal tax code, but it's often used to describe a broad category of defined contribution retirement plans, where the employer defines how much they plan to contribute in a given year and individual employees have their own accounts that they can take with them. But beyond that basic structure, they vary considerably in terms of how much the employer contributes, where the money is invested, or how much guidance they offer employees. This stuff matters immensely. A recent Center for Retirement Research brief shows just how much. The chart below from their brief starts with an employee making smart choices from the time he was 29 in 1982 until he turned 60 in 2013. He started young, contributed regularly, balanced his investment portfolio, and never cashed out. Those actions would net him $373,000 in retirement savings. But if he paid high fees on his investments that would cut his total down to $314,000. If, rather than transferring the entire balance when he changed jobs, he cashed out a little bit, that "leakage" would bring his retirement savings down to $236,000. Last, if he didn't contribute every year ("Intermittent contributions") and he waited to start saving well into his 30s (labeled "Immature System" in the graph), his total savings would drop to only $100,000. That's $273,000 in retirement savings in lost retirement savings.

Luckily, 401(k) plans are taking steps to address these problems. Due to federal rules requiring plans to improve their offerings and research showing that "nudges" and default options are powerful influences, plans have adopted smarter rules that protect individuals or at least encourage them into better savings habits. More plans automatically enroll workers, they recommend employees gradually increase their contributions over time, and they offer low-fee and life-cycle funds that help individuals make smarter investment decisions. And rather than being indifferent to what employees do with their savings when they leave, more plans reccommend individuals roll over their balance into a new retirement account or convert the entire balance into an annuity that will pay them a guaranteed amount throughout their retirement years.

By my read, the Michigan 401(k) proposal appears to do

noneonly some of these things. It would offer only a 4 percent employer matching contribution (with no minimum) and includenoneonly some of the protections mentioned above (*Correction: The state's defined contribution plan does offer low-fee and life-cycle investments, but it does not discourage leakage or establish sufficient savings levels as the default for new teachers.) Based on what we know about individual decision-making, it would not be a very good plan for teachers. Contrast that with Oklahoma, which recently passed a law shifting new state employees into a 401(k)-style plan with minimum employee and employer contributions and a matching contribution of up to 7 percent. Oklahoma would also support individuals to make smart investment decisions and encourage them to convert their savings to annuities rather than letting it "leak" out. An Oregon task force just released recommendations for a plan with many of these same protections. These examples suggest it's possible to design a 401(k)-style plan that supports workers in meeting their retirement savings needs.Teachers are the largest class of professional workers in the country so it's of national interest that they have a strong retirement plan. Today's pensions systems aren't meeting that goal, but change from traditional defined benefit plans need not be unworkable or unfavorable to teachers.

2. Michigan currently offers teachers a choice between a hybrid plan (which combines a traditional pension component with a very small defined contribution element) or a standalone, slightly larger defined contribution plan. The hybrid plan is the default option for teachers and isn't serving them well, but at least they have a choice. The proposed legislation would eliminate that choice altogether. If Michigan teachers truly believe that they're going to stay in their job for 25 or 30 years, the current hybrid plan might be their best option. This applies to only about 27 percent of Michigan teachers (or about 20 percent nationwide). But for the large majority of teachers--who don't know how long they'll teach, or don't know how long they'll teach in a given state, or just aren't confident that life won't get in the way--may want to choose a retirement plan that's more portable. Giving teachers a choice is a good thing, but with the odds and percentages at play, the default should be a well-structured, portable option. A well-structured 401(k) plan could meet that criteria; this one in particular would not.

Peter Greene and Neerav Kingsland have been debating the financial efficiency of public charter schools. Rather than wade into that debate, I'll take on one element of it that's rarely mentioned: teacher pensions.

To begin with, Kingsland is absolutely right to point out that states have engaged in fantastic accounting practices when it comes to their pension plans. States have not paid for pension costs on an honest accounting basis, and they have accrued billions of dollars in pension debt that avoids so-called "balanced budget" requirements.

Most importantly, Greene makes a big mistake when he writes that charters can avoid pension or other benefit costs through high turnover rates. In fact, the majority of states with charter schools require them to participate in the state pension plan. In those places, Greene's argument is exactly backward: Charter schools and their teachers pay the same high employer and employee contribution rates as all other schools, but higher turnover rates mean their teachers will get much less in return. Charter schools (and other urban schools with high turnover) subsidize the retirements of everybody else!

In fact, much of this story is broadly applicable beyond charter schools. Charters serve higher concentrations of low-income students, on average, than other schools and turnover tends to be higher in schools like that. But even within public school districts, some schools have much higher turnover rates than others. State pension plans treat them all the same, and we end up in a situation where there are some big winners at the expense of lots of small losers. Charter school teachers tend to be on the losing end.

Even in the places where charter schools are not required to participate, state pension plans impose rules that disadvantage teachers who move into or out of the system. Pension plans impose a retirement savings penalty on teachers who move across state lines or who leave teaching. Those same rules punish any teacher or principal who may wish to transfer between a traditional public school and a charter school.

Finally, there are those who see the current state of affairs--where new workers are propping up a system that has over-promised what it can actually deliver--and believe we can't afford to stop putting new workers into it. What they are essentially saying is the pension system is in such bad shape that we need to keep forcing new people into it, and that certain groups of teachers--especially ones who are newly entering the profession or ones who work in urban schools or charter schools--should sacrifice their own retirement savings for the good of the pension system. That's a terrible argument, and at some point policymakers will have to realize that placing new teachers into a bad pension system doesn't solve the problem, it just delays the inevitable.

Taxonomy: