Thousands of teachers and other public sector workers have been retiring in recent years, fueled in part by changes to their pensions. A January Governing magazine story found increased retirement rates in Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon and Wisconsin. Although this is often portrayed as a bad thing– the pension plan is pushing out scores of experienced workers!—new research from Maria D. Fitzpatrick and Michael F. Lovenheim in Education Next suggests we may not have reason to worry.

Faced with a budget crisis in the early 1990s, Illinois offered teachers a generous early retirement package. Large numbers of older, more experienced teachers took the offer, leading to a threefold increase in retirement rates. Over a two-year period, 10 percent of the total teaching workforce in Illinois retired.

None of the recent stories of mass retirements have been nearly as large as the 10 percent in Illinois, but what happened in Illinois can give us comfort that the retirements of today may not be as bad as predicted.

After the early retirement incentive program, Illinois had a dramatic influx of new teachers and a rapid decline in average teacher experience. The median retiring teacher had 27 years of experience and was replaced by a teacher with less than 3 years of experience. Across the state, average teacher experience declined and the number of new teachers increased substantially. All else equal, and since we know that teacher effectiveness rises with experience, we would have expected student achievement to go down.

But that’s not what happened. Instead, math and English test scores either stayed the same or went up. Importantly, those results held true for low-income, minority, and low-achieving students as well. There may be multiple reasons for this, but the massive retirements didn’t hurt student learning.

This study relied on school-wide test results, and we need more work on early retirement programs to replicate this finding, especially using data on individual teachers. Still, this is an important research finding and one that provides some insight into how the looming retirement of the Baby Boom generation may affect students. Along with other academic studies as well as surveys of teachers, it suggests there may be some experienced teachers hanging onto their jobs at the back end of their career as they wait to collect their pensions. To maximize their pension benefit—an understandable preference—some late-career teachers remain teaching even when they might otherwise prefer to retire. That may not be a good thing for teachers or students.

Finally, the paper also speculates on what happened financially under the early retirement incentive program. Using back-of-the-envelope calculations, the authors estimate that school districts saved $550.5 million by replacing older, more expensive teachers with younger, cheaper ones. But, importantly, that’s not the end of the story. The state pension plan was forced to start paying out benefits to teachers before it otherwise would have. The authors estimate the pension plan faced increased costs of $642.8 million. In other words, the early retirement incentive cost Illinois $92.3 million. That money won’t come directly out of individual district budgets—it’s shared by the state and all of its districts—and unlike salaries it doesn’t have to be paid for right away, but it is a real expense that must be paid eventually by state taxpayers.

This post originally appeared at Education Next.

Taxonomy:About half of all private sector workers do not have access to an employer retirement plan. Those employees must rely solely on Social Security and private savings for retirement. Many workers, though, lack the initiative, foresight, or adequate funds to plan ahead and save for retirement.

Recently, federal and state leaders have proposed a variety of solutions intended to address the need for greater retirement security. On the federal level, President Obama and Senator Tom Harkin, the Chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee, have proposed government-sponsored savings plan. Obama presented his idea for “MyRAs” in his February State of the Union Address; MyRA would allow employees to make after-tax contributions towards a tax-sheltered retirement savings account, similar to a RothIRA. Senator Harkin introduced a bill that would create a type of social insurance in which employees place a contribution into a pooled fund. At retirement, the employee would receive an annuity or monthly payments for the rest of his or her life. And last week, Senator Marco Rubio proposed that employees without an employer-sponsored savings plan become eligible to enroll in the Thrift Savings Plan offered to federal workers.

State leaders have been making similar proposals based on the work of the National Conference on Public Employee Retirement Systems (NCPERS). NCPERS proposed a “pension” plan for private workers in 2011. The NCPERS plan is modeled after a defined benefit cash balance plan and would provide employees with a lifetime annuity at retirement.

Government-sponsored retirement plans could solve a couple of problems. To begin with, each of these proposals would address, in their own way, the issue of mobility and whether a worker leaving his or her job could take the accrued retirement savings. Workers today are increasingly mobile and need plans that they can carry with them. Yet traditional state pension plans do not transfer into the private sector or across state lines. On the other hand, while 401k plans are theoretically portable, employees often forget about previous accounts or incur costly “leakage” penalties when they withdraw funds for non-retirement purposes after switching jobs. A state-based retirement savings plan would address some of these issues, but only the federal options would truly address the mobility and leakage problems. Another proposal that has been made and may address these issues is to expand Social Security, an already portable program that also avoids leakage.

The Harkin and NCPERS plans also propose using a multiple employer plan model, an “untapped market” according to Pensions and Investments. Pooled employer plans mean that costs and risk can be more evenly distributed. Multiple employer plans lessen administrative costs, spread the actuarial risk of plan funding, and better shield beneficiaries from market volatility. The plans would be overseen by independent trustees and professional money managers. Harkin’s plan would also include an oversight role for the Department of Labor.

In all cases, these proposals are intended to be an additional, not primary, stream of retirement income for workers. While not a panacea, government-sponsored plans could provide a low-cost savings vehicle for more workers to save for their retirement.

In a new Washington Post op-ed, Andrew Rotherham and I argue that the popular perception of teacher pensions is wrong. The media often portray public sector pensions as gold-plated benefits for all public workers. That has elements of truth but is a misdiagnosis of a larger problem, which is that pensions work well for the small fraction of teachers who stay in one plan for their entire career, but many more will leave their service as teachers with very little in the way of retirement savings. The real story is one of a small number of relatively big winners and a much larger group of losers.

This doesn’t fit with the common perception, but, in fact, many teachers get worse benefits than those offered in the private sector. This is most prominent for early-career workers. Under a federal law known as the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), private-sector employees must be eligible to retain some portion of their employer’s retirement contributions once they’ve been employed for three years and 100 percent of their employer’s contribution within six years.

One commenter on our piece asked if ERISA applied to public sector plans like those for teachers. The answer is no, ERISA's rules on pension accounting and retirement benefits apply only to private-sector employers. In fact, 17 states, including Maryland, Illinois, Michigan and New York, withhold all employer contributions for teachers until 10 years of service. States can and do offer worse benefits than those allowed in the private sector.

There is never enough space in an op-ed to address all dimensions of a complicated problem, but this story is part of a broader trend. While ERISA has gradually forced private plans to become more and more generous to early-career workers, public sector plans are moving in the opposite direction. ERISA’s original rules required private sector plans to make a portion of employer contributions available to employees within at least 10 years and all employer contributions within 15 years. In the late 1980s, Congress tightened those rules so that employees were eligible for employer contributions sooner. Starting in 2002, employers were required to offer their employees those contributions even sooner—some share of employer contributions within three years and 100 percent of them within six years. In addition, private companies have quietly adopted features like automatic enrollment and life-cycle funds that improve retirement offerings for private-sector workers.

The public sector is going in reverse. During the recent recession, twelve states lengthened their vesting period, the time a teacher must be employed before becoming eligible for pension benefits. They’ve also created less-generous plans for new employees. New York, for example, has six tiers in its defined benefit pension plan. The most experienced teachers are in Tier I. They have the most generous benefits. Teachers hired in the next tier are slightly worse off, and so on, until Tier VI, the plan offered to new teachers today. Nearly every state has its own tiers like this where new workers subsidize the costs of more expensive retirement plans for retirees and older workers.

As we conclude in our piece, this is part of a broader trend to get costs under control for public sector pensions. But “throwing up obstacles and making the plans stingier ignores the main purpose of retirement plans in the first place: to offer all workers a path to an attractive and secure retirement.” Read our entire piece here.

California discovered a $2.4 billion budget surplus from what it projected in January, but that money won't be going to any new, exciting program. It won't support the state's transition to new academic standards. It won't be going to expand kindergarten or offer pre-k to 4-year-olds. Governor Jerry Brown has other plans. He wants the money to go toward paying down the state's debt, especially the $74 billion unfunded liability from the state's teacher pension plan (CalSTRS).

To be clear, this is undoubtedly the right move for California. Governor Brown deserves credit for recognizing the problem and resisting calls for new spending when the state has such significant debts. Brown's pension funding proposal is merely a plan at this point, and politicians don't have a strong track record of fulfilling their pension promises. If Brown, future governors, or the state legislature aren't able to stick to a long-term funding plan, the problems will only get worse.

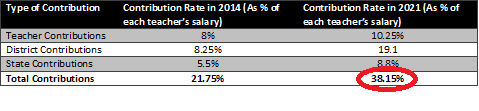

The current debt, and the plan to pay it down, are simply staggering. In order to pay off the full debt over 30 years, Brown's plan calls for increasing contribution rates across the board. Over a 7-year period, teacher contributions to the fund would rise from 8 to 10.25 percent of their salary. School district contributions would have to rise from 8.25 to 19.1 percent, and the state itself would contribute 8.8 percent, up from the current 5.5 percent. By 2021, nearly 40% of California teachers' total compensation will go toward paying down the pension plan's liabilities. (Due to the back-loaded nature of the pension plan's design, many teachers will never see that money at all.)

These contribution rates are set by the state legislature, and all California districts are required to participate in CalSTRS and pay the mandatory contribution rate. Districts would have no option if they wanted to provide their staff a different mix of compensation, even if they’d prefer to spend more resources on higher teacher salaries, hiring more teachers or making other investments. California districts won't be given that choice. Teachers won't either, because, unlike local salary schedules, the pension payments are not locally bargained.

All told, school district pension contributions would rise to $5 billion a year. Needless to say, $5 billion is a lot of money. For example, it's more than the state of California spends on transportation. It's about what the state general fund spends each year on the University of California and the California State University systems combined. $5 billion would buy 10 million iPad Airs, more than enough to give one to each of California's 6 million students. According to the NEA, California has 234,297 classroom teachers with an average salary of $70,126. The $5 billion would be equivalent to hiring 71,300 more teachers at current salaries or giving each current teacher a $21,340 raise*. Instead of having options on how they spend their money, school districts will have no choice but to withhold the pension funding.

California is a large and important state, but it's hardly unique in this situation. As states deal with large unfunded liabilities, contributions have and will continue to rise. School districts in California and across the country will be forced to cinch their budgets ever-tighter, squeezing out money for teachers and classrooms.

*These are merely illustrative. Benefit costs would actually drive these figures lower.

Taxonomy:Public pensions are not portable. A teacher with five years of experience in one state cannot freely transfer her service time if she moves to another state. Instead, she starts over. According to economists Robert Costrell and Michael Podgursky, mobile teachers face significant losses when moving between pension systems. A teacher who teaches for 30 years in one state system will have a significantly larger pension than a teacher who splits the same amount of service over two states. Pension systems reward employees who stay for a full career.

States have attempted to ameliorate the non-portability of pensions by “selling” service credit. Teachers who taught in one retirement system can “buy” back credit for the service they performed in another state, rather than relinquishing the time. For a hypothetical example, consider a teacher who taught for five years in Maryland and then moves to Virginia. In Virginia, she has zero service credits and must start over to reach a full-career pension. But if she buys service credit from the state, she can add more years towards her Virginia pension. Presumably buying back service years can help a teacher get a full-career pension sooner.

Unfortunately, though, pension plans exact transaction costs on mobile teachers that significantly hamper their savings. First, states limit the number of buyback years, often to five or ten years. The Virginia hybrid plan limits buyback credit to two years. The hypothetical ex-Marylander couldn’t purchase enough service credits to match her actual years of experience even if she could afford to do so.

Second, states charge prices that far exceed what teachers typically receive when cashing out of a state pension system. When a non-vested teacher leaves a system, she has the option of withdrawing her pension contributions. In 43 states, however, a teacher who leaves can only take back her own contributions and some interest; she loses the contributions her employer made on her behalf, which are often 10 or 15 percent of her total compensation.

Then, if she tries to take her reduced withdrawals and purchase service credits in her new state, she won’t have enough to cover the same number of years. That’s because states often charge the full actuarial cost to purchase service years. This means to buy a service year, teachers essentially need to pay the costs of contributions and interest had they worked in that state. In states such as Arkansas, Missouri, and Florida, a teacher must pay both the employee and employer contributions for the year she wants to purchase. In Virginia, a teacher is charged a multiplier of her current annual salary for service credit; the ex-Maryland teacher can only buy back two years of service for a total price tag of $10,552.34. However, this amount is almost double the required employee contributions a current Virginia teacher would pay over the course of a couple years. In the current Virginia hybrid plan, a teacher is required to make an employee contribution of 4 percent towards the defined benefit component of the plan, and a minimum 1 percent towards the defined contribution component of the plan. Over the course of two years, a teacher contributes a total of roughly $5,000. Like many states, Virginia sets service credit at a price tag that includes much more than just employee contributions.

Put together, this means that a non-vested teacher wishing to buy a year of service credit is expected to foot the entire bill (employee contributions, interest, plus employer contributions or a multiplier in certain states) while only having her own contributions from the previous state in her pocket.*

Lack of portability is a major roadblock for teachers. According to recent research, teachers have become increasingly more mobile over the past two decades. While Virginia and other states offer licensure reciprocity to out-of-state teachers, there’s no such thing yet as a reciprocal agreement for pensions. Instead, teachers must split their pensions across states, significantly decreasing their benefits, or make a costly purchase of service credit.

* There are high transition costs even for a teacher who vests into a state system and then moves. According to Costrell and Podgursky, a teacher who teaches for 15 years in California could purchase at most 3.7 years of service credits in Florida using all her withdrawal contributions from her time teaching in California.

Taxonomy:New York City has come up with a screwy new way to compensate its teachers. Although it's been paying its teachers on time and giving them raises for the last five years, Mayor Bill de Blasio decided to also give the city's teachers retroactive salary increases for working in 2009, 2010, and 2011 (but not 2012 or 2013). This form of retraoctive pay is unusual in its own right, and Mayor de Blasio has made some unique choices in how to distribute it. Those choices have significant implications for different types of teachers:

- Former Teachers: This group fares the worst. For anyone who taught in 2009, 2010, or 2011 but who is neither currently employed as a teacher in New York City nor retired, they get nothing. According to the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), the union representing city teachers, this group is somewhere between 4,000 and 8,200 former teachers.

- Recent Retirees: This group fares the best. The 10,808 New York City teachers who retired in 2010, 2011, or 2012 will receive an immediate lump sum payment of 100 percent of their back pay*.

- Upcoming Retirees: Anyone who retires before June 30, 2014 will also receive a lump sum payment for 100 percent of their back pay. A wave of another 4,000 teachers will likely take this option. Anyone who retires after June 30, 2014 will receive their full back pay delivered in five separate payments from 2015 through 2020.

- Mid-Career Teachers: Anyone who was teaching in 2009, 2010, and/or 2011, is still teaching, and remains in continuous employment (meaning they don't leave or take a year off for, say, childbirth), will receive a $1,000 payment immediately; 12.5 percent retroactive payments in 2015 and 2017; and 25 percent payments in 2018, 2019, and 2020. To receive their full retroactive payments (presumably for work they already did), teachers must remain in continuous employment until 2020. Using the pension plan's assumptions for retention, the average 15-year veteran in 2009 had about an 88 percent chance of making it until 2020.

- Early-Career Teachers: Using the pension plan's assumptions for retention, the average first-year teacher in 2009 had less than a 50-50 chance of making it to 2020. Many of them are already gone, but another 25 percent of the class of 2009 will leave between now and when they'll be eligible for full retroactive pay in 2020.

- Recently Hired and Future Teachers: Teachers hired in 2012 or later (obviously) get no retroactive pay. They will receive the benefits of a higher salary schedule, but they'll also be working for a distict paying off $2.5 billion in past promises to teachers. No one knows what New York City's budget will look like in 2020, but that's $2.5 billion that can't be spent on future raises, additional teachers, or other instructional costs.

*It's still unclear whether the retroactive pay will count toward the pension benefit calculation. If so, retirees would get an immediate and significant boost in their monthly benefit. We'll continue to monitor the story for further updates, but in the meantime read the UFT's description of the pay and benefits plan or their timeline chart explaining when everything will happen.

Taxonomy: